Winston Churchill (1874-1965) is remembered as the statesman who led Britain to victory during World War II. The man who had “nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.” The man who vowed to “fight them on the beaches.” The man who praised the heroes of the Battle of Britain with the line “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

But politics was Churchill’s secondary job. Politics got in the way of what he really wanted to do. His passion was writing and he was a professional author, who just happened to be one of the key politicians of the 20th century. He wrote many books between 1898 and 1961, and more collections of his speeches and writing were published after his death.

During the day, Churchill was a Member of Parliament, or President of the Board of Trade, or Chancellor of the Exchequer, or First Lord of the Admiralty, or Britain’s Prime Minister (twice). In the evenings, he wrote books.

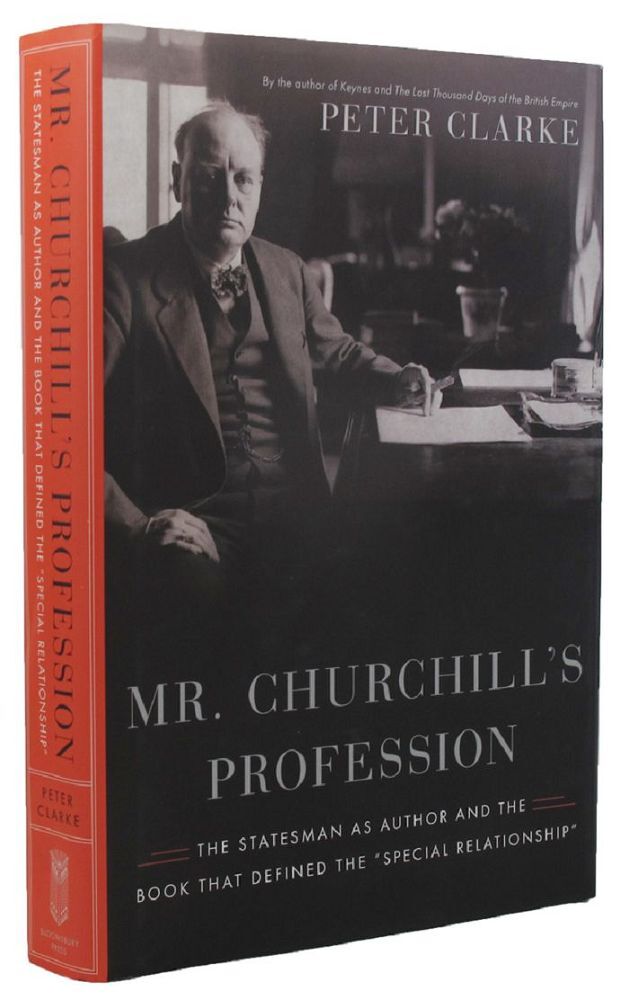

Peter Clarke, formerly Professor of Modern British History at Cambridge University who is retired and lives on Pender Island in British Columbia, has provided an insight into Churchill’s writing career with a fascinating book entitled Mr. Churchill’s Profession.

Mr Churchill’s Profession reveals Winston loved writing but, to put it bluntly, he also wrote because he needed the money.

“He entered politics (he became an MP in 1900) at a time when politicians need an outside source of support, a business or inherited wealth,” said Clarke. “Churchill was the youngest son of an impoverished aristocrat so he needed the money straight away and he turned to writing.”

Churchill – undoubtedly helped in the early days by his high profile and aristocratic heritage – became a successful author who earned large sums of money from his books but also from newspaper columns and speaking tours. And yet he mainly wrote in order to pay his bills, which were substantial. His salary from parliament usually did not come close to covering his considerable expenditure. He had purchased a rather run-down stately home in the Kent countryside called Chartwell and it became a huge drain on his financial resources.

“Chartwell was modest compared to his ancestral home of Blenheim Palace in Oxfordshire,” explains Clarke. “But it had 22 bedrooms, indoor and outdoor servants and a chauffeur. It required a lot of up-keep. He had substantial wine bills too and was quite old-fashioned in the way he provided for his children with trust funds. It’s really no mystery where his money went.”

Young Churchill started off in the army, which resulted in his first two books – The Story of the Malakand Field Force and The River War. The 25-year-old then dabbled in fiction with a novel called Savrola, but it wasn’t really his forte. History was his true calling.

His Boer War adventures as a war correspondent – which includes being captured by and escaping from the Boers - were detailed in London to Ladysmith via Pretoria.

In 1906, he published Lord Randolph Churchill – a biography of his own father where he aimed to redress some his father’s damaged reputation as a playboy politician who never fulfilled his potential.

During the 1930s, when his political career had stalled, Churchill wrote about another ancestor in Marlborough: His Life and Times – a four-volume epic published between 1933 and 1938 that detailed the life and achievements of John Churchill, the first Duke of Marlborough whose victories in Europe helped turn Britain into one of the key powers of the 18th century. Clarke describes Marlborough as Churchill’s “albatross” because of its behemoth size.

“Marlborough was written more like a clever lawyer than a dispassionate author,” adds Clarke when asked if Churchill was truly accurate when judging a notable relation. “Churchill had an agenda but you could say this about many other historians. Marlborough is definitely worth a read.”

A selection of books by Sir Winston Churchill

Clarke also recommends My Early Life as “a wonderful, witty and evocative account of his early years. He had an interesting story to tell and a good way of telling it.”

Churchill usually used a team of assistants, researchers, secretaries and proof-readers to write some of his books. “It was quite well known that he used a syndicate for writing after World War II but he also used research assistants in the 1930s to write Marlborough. It’s worth noting he didn’t write in longhand but dictated his books aloud to secretaries.

“Dictation is the reason there was no economy in his writing. It’s the old phrase that he ‘didn’t have time to make his books shorter.”’

After having his first book published in 1898, Churchill only stopped writing when the pressure of World War II became too much. He was still writing when recalled as Lord of the Admiralty in September 1939 but it didn’t last for long. “He had to put writing aside and put all his time in wartime oratory,” said Clarke.

His literary career set up his oratory of World War II. He had written about being a soldier, experienced the Boer War, been a minister during World War I, campaigned furiously for rearmament during the 1930s when his political career was in the wilderness and covered military history extensively in his writing. This author-politician thoroughly knew European warfare and what it took to win. His years of writing had been the perfect preparation.

It could be argued that Churchill’s Nobel Prize for Literature in 1953 (Ernest Hemingway won a year later) was really awarded for his wartime speeches rather than his writing. He left behind a unique legacy after a singular life of achievement in politics but also literature.