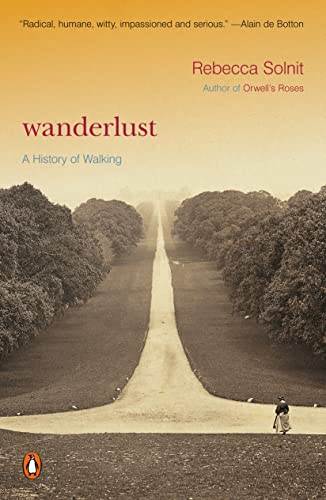

Items related to Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Synopsis

A passionate, thought-provoking exploration of walking as a political and cultural activity, from the author of Orwell's Roses

Drawing together many histories--of anatomical evolution and city design, of treadmills and labyrinths, of walking clubs and sexual mores--Rebecca Solnit creates a fascinating portrait of the range of possibilities presented by walking. Arguing that the history of walking includes walking for pleasure as well as for political, aesthetic, and social meaning, Solnit focuses on the walkers whose everyday and extreme acts have shaped our culture, from philosophers to poets to mountaineers. She profiles some of the most significant walkers in history and fiction--from Wordsworth to Gary Snyder, from Jane Austen's Elizabeth Bennet to Andre Breton's Nadja--finding a profound relationship between walking and thinking and walking and culture. Solnit argues for the necessity of preserving the time and space in which to walk in our ever more car-dependent and accelerated world."synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Rebecca Solnit is the author of numerous books, including Hope in the Dark, River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West, Wanderlust: A History of Walking, and As Eve Said to the Serpent: On Landscape, Gender, and Art, which was nominated for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism. In 2003, she received the prestigious Lannan Literary Award.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Wanderlust

A History of WalkingBy Rebecca SolnitPenguin Books

Copyright ©2001 Rebecca SolnitAll right reserved.

ISBN: 0140286012

Chapter One

Tracing a Headland:

An Introduction

Where does it start? Muscles tense. One leg a pillar, holding the body upright betweenthe earth and sky. The other a pendulum, swinging from behind. Heeltouches down. The whole weight of the body rolls forward onto the ball of thefoot. The big toe pushes off, and the delicately balanced weight of the bodyshifts again. The legs reverse position. It starts with a step and then another stepand then another that add up like taps on a drum to a rhythm, the rhythm ofwalking. The most obvious and the most obscure thing in the world, this walkingthat wanders so readily into religion, philosophy, landscape, urban policy, anatomy,allegory, and heartbreak.

The history of walking is an unwritten, secret history whose fragments can befound in a thousand unemphatic passages in books, as well as in songs, streets,and almost everyone's adventures. The bodily history of walking is that of bipedalevolution and human anatomy. Most of the time walking is merely practical, theunconsidered locomotive means between two sites. To make walking into an investigation,a ritual, a meditation, is a special subset of walking, physiologicallylike and philosophically unlike the way the mail carrier brings the mail and theoffice worker reaches the train. Which is to say that the subject of walking is, insome sense, about how we invest universal acts with particular meanings. Likeeating or breathing, it can be invested with wildly different cultural meanings,from the erotic to the spiritual, from the revolutionary to the artistic. Here thishistory begins to become part of the history of the imagination and the culture,of what kind of pleasure, freedom, and meaning are pursued at different times bydifferent kinds of walks and walkers. That imagination has both shaped and beenshaped by the spaces it passes through on two feet. Walking has created paths,roads, trade routes; generated local and cross-continental senses of place; shapedcities, parks; generated maps, guidebooks, gear, and, further afield, a vast libraryof walking stories and poems, of pilgrimages, mountaineering expeditions, meanders,and summer picnics. The landscapes, urban and rural, gestate the stories,and the stories bring us back to the sites of this history.

This history of walking is an amateur history, just as walking is an amateur act.To use a walking metaphor, it trespasses through everybody else's field?throughanatomy, anthropology, architecture, gardening, geography, political and culturalhistory, literature, sexuality, religious studies?and doesn't stop in any ofthem on its long route. For if a field of expertise can be imagined as a real field?anice rectangular confine carefully tilled and yielding a specific crop?then thesubject of walking resembles walking itself in its lack of confines. And though thehistory of walking is, as part of all these fields and everyone's experience, virtuallyinfinite, this history of walking I am writing can only be partial, an idiosyncraticpath traced through them by one walker, with much doubling back andlooking around. In what follows, I have tried to trace the paths that brought mostof us in my country, the United States, into the present moment, a history compoundedlargely of European sources, inflected and subverted by the vastly differentscale of American space, the centuries of adaptation and mutation here,and by the other traditions that have recently met up with those paths, notablyAsian traditions. The history of walking is everyone's history, and any writtenversion can only hope to indicate some of the more well-trodden paths in the author'svicinity?which is to say, the paths I trace are not the only paths.

I sat down one spring day to write about walking and stood up again, because adesk is no place to think on the large scale. In a headland just north of the GoldenGate Bridge studded with abandoned military fortifications, I went out walkingup a valley and along a ridgeline, then down to the Pacific. Spring had come afteran unusually wet winter, and the hills had turned that riotous, exuberant greenI forget and rediscover every year. Through the new growth poked grass from theyear before, bleached from summer gold to an ashen gray by the rain, part of thesubtler palette of the rest of the year. Henry David Thoreau, who walked morevigorously than me on the other side of the continent, wrote of the local, "An absolutelynew prospect is a great happiness, and I can still get this any afternoon.Two or three hours' walking will carry me to as strange a country as I expect everto see. A single farmhouse which I had not seen before is sometimes as good asthe dominions of the King of Dahomey. There is in fact a sort of harmony discoverablebetween the capabilities of the landscape within a circle of ten miles'radius, or the limits of an afternoon walk, and the threescore years and ten of humanlife. It will never become quite familiar to you."

These linked paths and roads form a circuit of about six miles that I began hikingten years ago to walk off my angst during a difficult year. I kept coming backto this route for respite from my work and for my work too, because thinking isgenerally thought of as doing nothing in a production-oriented culture, and doingnothing is hard to do. It's best done by disguising it as doing something,and the something closest to doing nothing is walking. Walking itself is the intentionalact closest to the unwilled rhythms of the body, to breathing and thebeating of the heart. It strikes a delicate balance between working and idling, beingand doing. It is a bodily labor that produces nothing but thoughts, experiences,arrivals. After all those years of walking to work out other things, it madesense to come back to work close to home, in Thoreau's sense, and to think aboutwalking.

Walking, ideally, is a state in which the mind, the body, and the world arealigned, as though they were three characters finally in conversation together,three notes suddenly making a chord. Walking allows us to be in our bodies andin the world without being made busy by them. It leaves us free to think withoutbeing wholly lost in our thoughts. I wasn't sure whether I was too soon or too latefor the purple lupine that can be so spectacular in these headlands, but milkmaidswere growing on the shady side of the road on the way to the trail, and they recalledthe hillsides of my childhood that first bloomed every year with an extravaganceof these white flowers. Black butterflies fluttered around me, tossedalong by wind and wings, and they called up another era of my past. Moving onfoot seems to make it easier to move in time; the mind wanders from plans to recollectionsto observations.

The rhythm of walking generates a kind of rhythm of thinking, and the passagethrough a landscape echoes or stimulates the passage through a series ofthoughts. This creates an odd consonance between internal and external passage,one that suggests that the mind is also a landscape of sorts and that walking is oneway to traverse it. A new thought often seems like a feature of the landscape thatwas there all along, as though thinking were traveling rather than making. Andso one aspect of the history of walking is the history of thinking made concrete?forthe motions of the mind cannot be traced, but those of the feet can.Walking can also be imagined as a visual activity, every walk a tour leisurelyenough both to see and to think over the sights, to assimilate the new into theknown. Perhaps this is where walking's peculiar utility for thinkers comes from.The surprises, liberations, and clarifications of travel can sometimes be garneredby going around the block as well as going around the world, and walking travelsboth near and far. Or perhaps walking should be called movement, not travel,for one can walk in circles or travel around the world immobilized in a seat, anda certain kind of wanderlust can only be assuaged by the acts of the body itself inmotion, not the motion of the car, boat, or plane. It is the movement as well asthe sights going by that seems to make things happen in the mind, and this iswhat makes walking ambiguous and endlessly fertile: it is both means and end,travel and destination.

The old red dirt road built by the army had begun its winding, uphill coursethrough the valley. Occasionally I focused on the act of walking, but mostly itwas unconscious, the feet proceeding with their own knowledge of balance, ofsidestepping rocks and crevices, of pacing, leaving me free to look at the roll ofhills far away and the abundance of flowers close up: brodia; the pink paperyblossoms whose name I never learned; an abundance of cloverlike sourgrass inyellow bloom; and then halfway along the last bend, a paperwhite narcissus.After twenty minutes trudge uphill I stopped to smell it. There used to be a dairyin this valley, and the foundations of a farmhouse and a few straggling old fruittrees still survive somewhere down below, on the other side of the wet, willow-crowdedvalley bottom. It was a working landscape far longer than a recreationalone: first came the Miwok Indians, then the agriculturists, themselves rooted outafter a century by the military base, which closed in the 1970s, when coasts becameirrelevant to an increasingly abstract and aerial kind of war. Since the1970s, this place has been turned over to the National Park Service and to peoplelike me who are heirs to the cultural tradition of walking in the landscape forpleasure. The massive concrete gun emplacements, bunkers, and tunnels willnever disappear as the dairy buildings have, but it must have been the dairy familiesthat left behind the live legacy of garden flowers that crop up among the nativeplants.

Walking is meandering, and I meandered from my cluster of narcissus in thecurve of the red road first in thought and then by foot. The army road reachedthe crest and crossed the trail that would take me across the brow of the hill, cuttinginto the wind and downhill before its gradual ascent to the western side ofthe crest. On the ridgetop up above this footpath, facing into the next valleynorth, was an old radar station surrounded by an octagon of fencing. The oddcollection of objects and cement bunkers on an asphalt pad were part of a Nikemissile guidance system, a system for directing nuclear missiles from their base inthe valley below to other continents, though none were ever launched from herein war. Think of the ruin as a souvenir from the canceled end of the world.

It was nuclear weapons that first led me to walking history, in a trajectory assurprising as any trail or train of thought. I became in the 1980s an antinuclearactivist and participated in the spring demonstrations at the Nevada Test Site, aDepartment of Energy site the size of Rhode Island in southern Nevada wherethe United States has been detonating nuclear bombs?more than a thousand todate?since 1951. Sometimes nuclear weapons seemed like nothing more thanintangible budget figures, waste disposal figures, potential casualty figures, to beresisted by campaigning, publishing, and lobbying. The bureaucratic abstractnessof both the arms race and the resistance to it could make it hard to understandthat the real subject was and is the devastation of real bodies and realplaces. At the test site, it was different. The weapons of mass destruction were beingexploded in a beautifully stark landscape we camped near for the week or twoof each demonstration (exploded underground after 1963, though they oftenleaked radiation into the atmosphere anyway and always shook the earth). We?thatwe made up of the scruffy American counterculture, but also of survivors ofHiroshima and Nagasaki, Buddhist monks and Franciscan priests and nuns, veteransturned pacifist, renegade physicists, Kazakh and German and Polynesianactivists living in the shadow of the bomb, and the Western Shoshone, whoseland it was?had broken through the abstractions. Beyond them were the actualitiesof places, of sights, of actions, of sensations?of handcuffs, thorns, dust,heat, thirst, radiation risk, the testimony of radiation victims?but also of spectaculardesert light, the freedom of open space, and the stirring sight of the thousandswho shared our belief that nuclear bombs were the wrong instrument withwhich to write the history of the world. We bore a kind of bodily witness to ourconvictions, to the fierce beauty of the desert, and to the apocalypses being preparednearby. The form our demonstrations took was walking: what was on thepublic-land side of the fence a ceremonious procession became, on the off-limitsside, an act of trespass resulting in arrest. We were engaging, on an unprecedentedlygrand scale, in civil disobedience or civil resistance, an American traditionfirst articulated by Thoreau.

Thoreau himself was both a poet of nature and a critic of society. His famousact of civil disobedience was passive?a refusal to pay taxes to support war andslavery and an acceptance of the night in jail that ensued?and it did not overlapdirectly with his involvement in exploring and interpreting the local landscape,though he did lead a huckleberrying party the day he got out of jail. In our actionsat the test site the poetry of nature and criticism of society were united inthis camping, walking, and trespassing, as though we had figured out how aberrying party could be a revolutionary cadre. It was a revelation to me, the waythis act of walking through a desert and across a cattle guard into the forbiddenzone could articulate political meaning. And in the course of traveling to thislandscape, I began to discover other western landscapes beyond my coastal regionand to explore those landscapes and the histories that had brought me tothem?the history not only of the development of the West but of the Romantictaste for walking and landscape, the democratic tradition of resistance and revolution,the more ancient history of pilgrimage and walking to achieve spiritualgoals. I found my voice as a writer in describing all the layers of history thatshaped my experiences at the test site. And I began to think and to write aboutwalking in the course of writing about places and their histories.

Of course walking, as any reader of Thoreau's essay "Walking" knows, inevitablyleads into other subjects. Walking is a subject that is always straying.Into, for example, the shooting stars below the missile guidance station in thenorthern headlands of the Golden Gate. They are my favorite wildflower, thesesmall magenta cones with their sharp black points that seem aerodynamicallyshaped for a flight that never comes, as though they had evolved forgetful of thefact that flowers have stems and stems have roots. The chaparral on both sides ofthe trail, watered by the condensation of the ocean fog through the dry monthsand shaded by the slope's northern exposure, was lush. While the missile guidancestation on the crest always makes me think of the desert and of war, thesebanks below always remind me of English hedgerows, those field borders withtheir abundance of plants, birds, and that idyllic English kind of countryside.There were ferns here, wild strawberries, and, tucked under a coyote bush, a clusterof white iris in bloom.

Although I came to think about walking, I couldn't stop thinking about everythingelse, about the letters I should have been writing, about the conversationsI'd been having. At least when my mind strayed to the phone conversation withmy friend Sono that morning, I was still on track. Sono's truck had been stolenfrom her West Oakland studio, and she told me that though everyone respondedto it as a disaster, she wasn't all that sorry it was gone, or in a hurry to replace it.There was a joy, she said, to finding that her body was adequate to get her whereshe was going, and it was a gift to develop a more tangible, concrete relationshipto her neighborhood and its residents. We talked about the more stately sense oftime one has afoot and on public transit, where things must be planned andscheduled beforehand, rather than rushed through at the last minute, and aboutthe sense of place that can only be gained on foot. Many people nowadays livein a series of interiors?home, car, gym, office, shops?disconnected from eachother. On foot everything stays connected, for while walking one occupies thespaces between those interiors in the same way one occupies those interiors. Onelives in the whole world rather than in interiors built up against it.

The narrow trail I had been following came to an end as it rose to meet theold gray asphalt road that runs up to the missile guidance station. Stepping frompath to road means stepping up to see the whole expanse of the ocean, spreadinguninterrupted to Japan. The same shock of pleasure comes every time I cross thisboundary to discover the ocean again, an ocean shining like beaten silver on thebrightest days, green on the overcast ones, brown with the muddy runoff of thestreams and rivers washing far out to sea during winter floods, an opalescent mottlingof blues on days of scattered clouds, only invisible on the foggiest days,when the salt smell alone announces the change. This day the sea was a solid bluerunning toward an indistinct horizon where white mist blurred the transition tocloudless sky. From here on, my route was downhill. I had told Sono about an adI found in the Los Angeles Times a few months ago that I'd been thinking about eversince. It was for a CD-ROM encyclopedia, and the text that occupied a wholepage read, "You used to walk across town in the pouring rain to use our encyclopedias.We're pretty confident that we can get your kid to click and drag." I thinkit was the kid's walk in the rain that constituted the real education, at least of thesenses and the imagination. Perhaps the child with the CD-ROM encyclopediawill stray from the task at hand, but wandering in a book or a computer takesplace within more constricted and less sensual parameters. It's the unpredictableincidents between official events that add up to a life, the incalculable that givesit value. Both rural and urban walking have for two centuries been prime ways ofexploring the unpredictable and the incalculable, but they are now under assaulton many fronts.

The multiplication of technologies in the name of efficiency is actually eradicatingfree time by making it possible to maximize the time and place for productionand minimize the unstructured travel time in between. New timesavingtechnologies make most workers more productive, not more free, in a world thatseems to be accelerating around them. Too, the rhetoric of efficiency aroundthese technologies suggests that what cannot be quantified cannot be valued?thatthat vast array of pleasures which fall into the category of doing nothing inparticular, of woolgathering, cloud-gazing, wandering, window-shopping, arenothing but voids to be filled by something more definite, more productive, orfaster paced. Even on this headland route going nowhere useful, this route thatcould only be walked for pleasure, people had trodden shortcuts between theswitchbacks as though efficiency was a habit they couldn't shake. The indeterminacyof a ramble, on which much may be discovered, is being replaced by the determinateshortest distance to be traversed with all possible speed, as well as bythe electronic transmissions that make real travel less necessary. As a member ofthe self-employed whose time saved by technology can be lavished on daydreamsand meanders, I know these things have their uses, and use them?atruck, a computer, a modem?myself, but I fear their false urgency, their call tospeed, their insistence that travel is less important than arrival. I like walking becauseit is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about threemiles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed ofthought, or thoughtfulness.

Walking is about being outside, in public space, and public space is also beingabandoned and eroded in older cities, eclipsed by technologies and services thatdon't require leaving home, and shadowed by fear in many places (and strangeplaces are always more frightening than known ones, so the less one wanders thecity the more alarming it seems, while the fewer the wanderers the more lonelyand dangerous it really becomes). Meanwhile, in many new places, public spaceisn't even in the design: what was once public space is designed to accommodatethe privacy of automobiles; malls replace main streets; streets have no sidewalks;buildings are entered through their garages; city halls have no plazas; and everythinghas walls, bars, gates. Fear has created a whole style of architecture and urbandesign, notably in southern California, where to be a pedestrian is to beunder suspicion in many of the subdivisions and gated "communities." At thesame time, rural land and the once-inviting peripheries of towns are being swallowedup in car-commuter subdivisions and otherwise sequestered. In someplaces it is no longer possible to be out in public, a crisis both for the privateepiphanies of the solitary stroller and for public space's democratic functions. Itwas this fragmentation of lives and landscapes that we were resisting long ago, inthe expansive spaces of the desert that temporarily became as public as a plaza.

And when public space disappears, so does the body as, in Sono's fine term,adequate for getting around. Sono and I spoke of the discovery that our neighborhoods?whichare some of the most feared places in the Bay Area?aren't allthat hostile (though they aren't safe enough to let us forget about safety altogether).I have been threatened and mugged on the street, long ago, but I have athousand times more often encountered friends passing by, a sought-for book ina store window, compliments and greetings from my loquacious neighbors, architecturaldelights, posters for music and ironic political commentary on wallsand telephone poles, fortune-tellers, the moon coming up between buildings,glimpses of other lives and other homes, and street trees noisy with songbirds.The random, the unscreened, allows you to find what you don't know you arelooking for, and you don't know a place until it surprises you. Walking is one wayof maintaining a bulwark against this erosion of the mind, the body, the landscape,and the city, and every walker is a guard on patrol to protect the ineffable.

Perhaps a third of the way down the road that wandered to the beach, an orangenet was spread. It looked like a tennis net, but when I reached it I saw thatit fenced off a huge new gap in the road. This road has been crumbling since I beganto walk on it a decade ago. It used to roll uninterruptedly from sea toridgetop. Along the coastal reach of the road a little bite appeared in 1989 thatone could edge around, then a little trail detoured around the growing gap. Withevery winter's rain, more and more red earth and road surface crumbled away,sliding into a heap at the ruinous bottom of the steep slope the road had once cutacross. It was an astonishing sight at first, this road that dropped off into thin air,for one expects roads and paths to be continuous. Every year more of it hasfallen. And I have walked this route so often that every part of it springs associationson me. I remember all the phases of the collapse and how different a personI was when the road was complete. I remember explaining to a friend on thisroute almost three years earlier why I liked walking the same way over and over.I joked, in a bad adaptation of Heraclitus's famous dictum about rivers, that younever step on the same trail twice; and soon afterward we came across the newstaircase that cut down the steep hillside, built far enough inland that the erosionwouldn't reach it for many years to come. If there is a history of walking, then ittoo has come to a place where the road falls off, a place where there is no publicspace and the landscape is being paved over, where leisure is shrinking and beingcrushed under the anxiety to produce, where bodies are not in the world but onlyindoors in cars and buildings, and an apotheosis of speed makes those bodiesseem anachronistic or feeble. In this context, walking is a subversive detour, thescenic route through a half-abandoned landscape of ideas and experiences.

I had to circumnavigate this new chunk bitten out of the actual landscape bygoing to a new detour on the right. There's always a moment on this circuit whenthe heat of climbing and the windblock the hills provide give way to the descentinto ocean air, and this time it came at the staircase past the scree of a fresh cutinto the green serpentine stone of the hill. From there it wasn't far to the switchbackleading to the other half of the road, which winds closer and closer to thecliffs above the ocean, where waves shatter into white foam over the dark rockswith an audible roar. Soon I was at the beach, where surfers sleek as seals in theirblack wet suits were catching the point break at the northern edge of the cove,dogs chased sticks, people lolled on blankets, and the waves crashed, thensprawled into a shallow rush uphill to lap at the feet of those of us walking on thehard sand of high tide. Only a final stretch remained, up over a sandy crest andalong the length of the murky lagoon full of water birds.

It was the snake that came as a surprise, a garter snake, so called because ofthe yellowish stripes running the length of its dark body, a snake tiny and enchantingas it writhed like waving water across the path and into the grasses onone side. It didn't alarm me so much as alert me. Suddenly I came out of mythoughts to notice everything around me again?the catkins on the willows, thelapping of the water, the leafy patterns of the shadows across the path. And thenmyself, walking with the alignment that only comes after miles, the loose diagonalrhythm of arms swinging in synchronization with legs in a body that felt longand stretched out, almost as sinuous as the snake. My circuit was almost finished,and at the end of it I knew what my subject was and how to address it in a way Ihad not six miles before. It had come to me not in a sudden epiphany but with agradual sureness, a sense of meaning like a sense of place. When you give yourselfto places, they give you yourself back; the more one comes to know them,the more one seeds them with the invisible crop of memories and associationsthat will be waiting for you when you come back, while new places offer up newthoughts, new possibilities. Exploring the world is one of the best ways of exploringthe mind, and walking travels both terrains.

Continues...

Excerpted from Wanderlustby Rebecca Solnit Copyright ©2001 by Rebecca Solnit. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

£ 4.45 shipping from U.S.A. to United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Seller: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. It's a well-cared-for item that has seen limited use. The item may show minor signs of wear. All the text is legible, with all pages included. It may have slight markings and/or highlighting. Seller Inventory # 0140286012-8-1

Quantity: 1 available

Wanderlust

Seller: Rarewaves.com UK, London, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: New. A passionate, thought-provoking exploration of walking as a political and cultural activity, from the author of Orwell's Roses Drawing together many histories--of anatomical evolution and city design, of treadmills and labyrinths, of walking clubs and sexual mores--Rebecca Solnit creates a fascinating portrait of the range of possibilities presented by walking. Arguing that the history of walking includes walking for pleasure as well as for political, aesthetic, and social meaning, Solnit focuses on the walkers whose everyday and extreme acts have shaped our culture, from philosophers to poets to mountaineers. She profiles some of the most significant walkers in history and fiction--from Wordsworth to Gary Snyder, from Jane Austen's Elizabeth Bennet to Andre Breton's Nadja--finding a profound relationship between walking and thinking and walking and culture. Solnit argues for the necessity of preserving the time and space in which to walk in our ever more car-dependent and accelerated world. Seller Inventory # LU-9780140286014

Quantity: Over 20 available

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: good. Befriedigend/Good: Durchschnittlich erhaltenes Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit Gebrauchsspuren, aber vollständigen Seiten. / Describes the average WORN book or dust jacket that has all the pages present. Seller Inventory # M00140286012-G

Quantity: 1 available

Wanderlust : A History of Walking

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK, Woodford Green, United Kingdom

Condition: As New. Unread book in perfect condition. Seller Inventory # 492333

Quantity: 3 available

Wanderlust : A History of Walking

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK, Woodford Green, United Kingdom

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 492333-n

Quantity: 3 available

Wanderlust: A History of Walking (Paperback)

Seller: CitiRetail, Stevenage, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Drawing together many histories-of anatomical evolution and city design, of treadmills and labyrinths, of walking clubs and sexual mores-Rebecca Solnit creates a fascinating portrait of the range of possibilities presented by walking. Arguing that the history of walking includes walking for pleasure as well as for political, aesthetic, and social meaning, Solnit focuses on the walkers whose everyday and extreme acts have shaped our culture, from philosophers to poets to mountaineers. She profiles some of the most significant walkers in history and fiction-from Wordsworth to Gary Snyder, from Jane Austen's Elizabeth Bennet to Andre Breton's Nadja-finding a profound relationship between walking and thinking and walking and culture. Solnit argues for the necessity of preserving the time and space in which to walk in our ever more car-dependent and accelerated world. Profiling some of the most significant walkers in history and fiction, Solnit presents a delightful and brilliantly conceived meditation on the art of walking. Shipping may be from our UK warehouse or from our Australian or US warehouses, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780140286014

Quantity: 1 available

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Seller: Kennys Bookshop and Art Galleries Ltd., Galway, GY, Ireland

Condition: New. 2000. Illustrated. Paperback. . . . . . Seller Inventory # V9780140286014

Quantity: 15 available

Wanderlust

Seller: Books Puddle, New York, NY, U.S.A.

Condition: New. pp. 336. Seller Inventory # 26658359

Quantity: 3 available

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Seller: California Books, Miami, FL, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780140286014

Quantity: Over 20 available

Wanderlust: A History of Walking

Seller: Revaluation Books, Exeter, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Brand New. reissue edition. 336 pages. 8.25x6.25x0.75 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # __0140286012

Quantity: 1 available