Items related to At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor:...

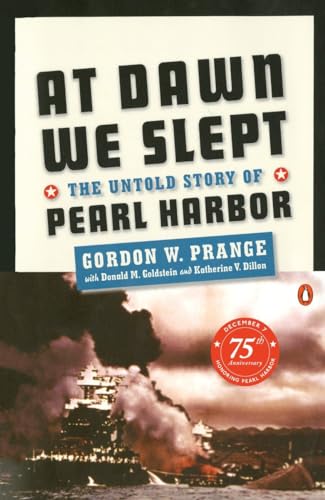

At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor; Revised Edition - Softcover

Synopsis

Revisit the definitive book on Pearl Harbor in advance of the 78th anniversary (December 7, 2019) of the "date which will live in infamy"

At 7:53 a.m., December 7, 1941, America's national consciousness and confidence were rocked as the first wave of Japanese warplanes took aim at the U.S. Naval fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor. As intense and absorbing as a suspense novel, At Dawn We Slept is the unparalleled and exhaustive account of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. It is widely regarded as the definitive assessment of the events surrounding one of the most daring and brilliant naval operations of all time. Through extensive research and interviews with American and Japanese leaders, Gordon W. Prange has written a remarkable historical account of the assault that-sixty years later-America cannot forget.

"The reader is bound to feel its power....It is impossible to forget such an account." ―The New York Times Book Review

"At Dawn We Slept is the definitive account of Pearl Harbor." ―Chicago Sun-Times

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Gordon W. Prange (1910-1980) served during World War II as an officer in the naval reserve and, during the occupation of Japan, served in the General Headquarters as a civilian. He was chief of General Douglas McArthur's G-2 Historical Section and director of the Military History Section. He taught history at the University of Maryland from 1937 until his death.

From the Back Cover

THE MONUMENTAL AND DEFINITIVE STUDY OF THE JAPANESE ATTACK ON PEARL HARBOR

At 7:53 A.M., December 7, 1941, America's national consciousness and confidence were rocked as the first wave of Japanese warplanes targeted the U.S. Pacific Fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor. As intense and absorbing as a suspense novel, At Dawn We Slept is an unparalleled, exhaustive account of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor that is widely regarded as the definitive assessment of the events surrounding one of the most daring and brilliant naval operations of all time. Through extensive research and interviews with American and Japanese leaders, Gordon W. Prange assembled a remarkable historical study that examines the assault that -- sixty years later -- America cannot forget.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

CHAPTER 1

“CANCER OF THE PACIFIC”

Long before sunrise on New Year’s Day, 1941, Emperor Hirohito rose to begin the religious service at the court marking the 2,601st anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire. No doubt he prayed for his nation and for harmony in the world. For this mild, peaceable man himself had chosen the word Showa—“enlightened peace”—to characterize his reign.

But in statements greeting the new year, Japanese leaders prophesied strife and turmoil. Veteran journalist Soho Tokutomi warned of storms ahead: “There is no denying that the seas are high in the Pacific. . . . The time has come for the Japanese to make up their minds to reject any who stand in the way of their country. . . .”

What true son of Nippon could doubt who stood in the way? Relations between the United States and Japan left tremendous room for improvement. Japan surged ahead under full sail on a voyage of expansion that dated back to 1895. Riding the winds of conquest, Japan invaded North China in 1937. Though it tried desperately to “solve” what it euphemistically termed the China Incident, it remained caught in a whirlpool that sucked down thousands upon thousands of its young men, tons upon tons of military equipment, and millions of yen. Still, nothing could stop its compulsive drive deeper and deeper into the heart of that tormented land. Thus, the unresolved China problem became the curse of Japan’s foreign policy.

Japan turned southward in 1939. On February 10 it took over Hainan Island off the southern coast of China. In March of the same year Japan laid claim to the Spratlys—coral islands offering potential havens for planes and small naval craft, located on a beautiful navigational fix between Saigon and North Borneo, Manila, and Singapore.

With the fall of France in 1940 Japan stationed troops in northern French Indochina, its key stepping-stone to further advancement southward. And dazzled by Hitler’s military exploits, it joined forces with Germany and Italy, signing the Tripartite Pact on September 27, 1940. By this treaty the three partners agreed to “assist one another with all political, economic and military means when one of the three Contracting Parties is attacked by a power at present not involved in the European War or in the Sino-Japanese conflict.” Inasmuch as no major nation remained uninvolved except the United States and the Soviet Union—and Germany had a nonaggression pact with the latter—the target of this treaty stood out with blinding clarity.

By 1941, that fateful Year of the Snake, Japan poised for further expansionist adventures into Southeast Asia—Malaya, the Philippines, and the Netherlands East Indies. The Japanese convinced themselves that necessity and self-protection demanded they take over the vast resources of these promised lands to break through real or imagined encirclement and beat off the challenge of any one or a combination of their international rivals—the United States, Great Britain, and Soviet Russia.

Throughout the early years of Japan’s emergence, the United States cheered on the Japanese, whom they regarded in a measure as their protégés. But in time it became apparent that the “plucky Little Japs” were not only brave and clever but dangerous and a bit on the devious side. By New Year’s Day of 1941 knowledgeable people in both countries already believed that an open clash would be only a matter of time. Even Ambassador Joseph C. Grew, a friend of Japan, could find no silver lining. “It seems to me increasingly clear that we are bound to have a showdown some day, and the principal question at issue is whether it is to our advantage to have that showdown sooner or have it later,” he lamented in a “Dear Frank” letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt on December 14, 1940.

Events in Europe inevitably colored the American attitude toward the Japanese, who labored under the self-imposed handicap of their alliance with Adolf Hitler, regarded by most Americans as little less than the Father of Evil. Japan’s strong-arm methods of persuading Vichy to permit Japanese troops to enter northern Indochina smacked of Benito Mussolini’s famous “dagger in the back” treatment of France. Now all signs pointed to the Netherlands East Indies as next on the list. The United States had to consider Japan in the context of its Axis alliance, for aid and concessions to Tokyo in effect meant aid and concessions to Berlin and Rome.

In essence China was the touchstone of Japanese-American relations, yet China was only part of the so-called Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, a concept the very fluidity of which made the democracies uneasy. The Japanese never tired of expounding the principle in the loftiest phrases but fought shy of actually stating in geographical terms just what “Greater East Asia” covered. Presumably it would expand as Japan moved outward to include all that the traffic would bear.

To the Japanese the fulfillment of this dream was imperative. “I am convinced that the firm establishment of a Mutual Prosperity Sphere in Greater East Asia is absolutely necessary to the continued existence of this country,” declared Japan’s premier, Prince Fumimaro Konoye, on January 24.

Japan had a long list of grievances against the United States, the foremost being the recognition of the Chiang Kai-shek regime and the nonrecognition of Manchukuo. The very presence in Asia of the United States, along with the European powers, was a constant irritation to Japanese pride. The press lost no occasion to assure such intruders that Japan would slam the Open Door in their faces. “Japan must remove all elements in East Asia which will interfere with its plans,” asserted the influential Yomiuri. “Britain, the United States, France and the Netherlands must be forced out of the Far East. Asia is the territory of the Asiatics. . . .”

On a number of scores the Japanese objected vociferously to American aid to Great Britain and to Anglo-American cooperation. In the first place, Britain was at war with Japan’s allies, Germany and Italy, so what helped the British hindered the Axis. In the second, Japan considered that Washington’s bolstering of London perpetuated the remnants of British colonialism and hence the obnoxious presence of European flags on Asian soil.

Japanese anger also focused on the embargoes which the United States had slapped on American exports to Japan. By the end of 1940 Washington had cut it off from all vital war materials except petroleum. As far back as 1938 the United States had placed Japan under the so-called moral embargo. The termination on January 26, 1940, of the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation of 1911 removed the legal obstacle to actual restrictions. Beginning in July 1940, Washington placed all exports of aviation fuel and high-grade scrap iron and steel under federal license and control. In September 1940, after Japanese forces moved into northern Indochina, Roosevelt finally announced an embargo on scrap iron and steel to Japan. Thus, by the end of that year Japan had begun to experience a real pinch and a shadow of genuine fear mingled with its resentment of these discriminatory measures.

Tokyo also had an old bone to pick with Washington—the immigration policy which excluded Japanese from American shores and refused United States citizenship to those Japanese residents not actually born there.

Above all, Japan considered America’s huge naval expansion program aimed directly at it. Since the stationing of a large segment of the Fleet at Pearl Harbor in the spring of 1940, the United States Navy had stood athwart Japan’s path—a navy which Japanese admirals thought capable of menacing their nation’s very existence.

Since Commodore Matthew Perry had opened Japan to the modern world, the two nations had enjoyed a unique history of friendship and mutually profitable trade. Yet now they stood face-to-face like two duelists at the salute. The Japanese had a name for this ugly situation: Taiheiyo-no-gan (“Cancer of the Pacific”).

But the Japanese would try the hand of diplomacy before they unsheathed the sword. If they could keep the United States immobilized in the Pacific by peaceful means, they would prefer to do so. To negotiate their differences with Washington, in November 1940 Tokyo selected as ambassador Admiral Kichisaburo Nomura. Called out of retirement at sixty-four, Nomura had filled numerous important positions in his long, illustrious career in the Navy. During a tour as naval attaché in Washington he became friendly with the then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt. More important, Nomura felt at home in the United States and cherished his American friends. Seldom have two nations at official loggerheads been represented by two such men of mutual goodwill as Grew and Nomura—two physicians who would make every effort to help cure the “Cancer of the Pacific.”

At six feet, Nomura loomed over most of his countrymen. On April 29, 1932, when he was attending a celebration in Shanghai, a Chinese terrorist had thrown a bomb into a group of Japanese dignitaries. The explosion robbed Nomura of his right eye and also crippled him, so that he walked with a limp for the rest of his life. In repose thoughtful, even a little anxious, his broad, good-natured face frequently beamed with jovial friendliness. All Japan knew him to be a man of sincerity, moderation, and liberality of thought, a sturdy opponent of the jingoists. He advocated peace and friendship with the United States; in American naval circles, consequently, he was both liked and respected.

Until the last moment Japan’s fire-eating expansionists, along with the Germans in Tokyo, tried to block Nomura’s appointment. Indeed, he himself had not sought the post. Throughout the late summer and early fall of 1940 the admiral consistently refused the offer, despite the persistent pleas of Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka. Only when his moderate naval colleagues implored him to accept and help reach an agreement with the United States did he reluctantly consent. Not that he considered the prospects entirely hopeless, but he had to admit that conditions were “very bad,” and he feared that “the situation would probably get worse.”

During numerous talks with Prime Minister Konoye, War Minister Hideki Tojo, and others, Nomura cautioned them not to expect miracles of him; the question of war or peace was beyond his powers as a single representative of the Japanese government. In the postwar years, when Nomura tried to explain how he felt during those tense days in Washington in 1941, he quoted a Japanese proverb: “When a big house falls, one pillar cannot stop it.”

Little wonder that on January 1, 1941, the official Japan Times and Advertiser admitted that although Nomura’s appointment was widely approved, “the role he is to play at Washington is no enviable one. When it is certain that Japanese diplomacy will be governed first and foremost by Axis motives, relations with the United States are pregnant with no end of potential issues.”

On January 20, 1941, just three days before sailing, Nomura spent about half an hour with Grew. The American ambassador certainly did not expect Nomura to reverse the tide. As he said in his diary, “The only potential usefulness I can see in Admiral Nomura’s appointment lies in the hope that he will honestly report to his Government what the American government and people are thinking, writing and saying.”

Grew kept a sharp, uneasy eye on the developments in Tokyo. Tall, dignified, with impeccable manners, he appeared to be the perfect senior career diplomat. A smooth thatch of snowy hair topped an intelligent, attractive face. Beneath heavy black brows the candid dark eyes opened to all possible contingencies yet looked out on mankind with good humor and common sense.

After almost nine years on the job he ranked as doyen of Tokyo’s diplomatic colony. Limited in part by deafness, Grew never mastered the Japanese language, but his wife spoke it excellently. Alice Grew had a special link with Japan, being the granddaughter of Commodore Perry. Blessed with a sharp mind and mature judgment, Grew became a shrewd observer of the Japanese scene and called the shots exactly as he saw them, both in his reports to Washington and in his conferences with Japanese leaders.

“With all our desire to keep America out of war and at peace with all nations, especially with Japan, it would be the height of folly to allow ourselves to be lulled into a feeling of false security,” Grew wrote on January 1, 1941, in his diary—that invaluable manuscript in which he not only recorded in detail the major diplomatic and political events of the day but also blew off steam when the pressure grew too great. Nevertheless, even when the Japanese most irritated him, his language was that of an affectionate father toward a beloved but exasperating son. “Japan, not we, is on the warpath . . .” he continued. “If those Americans who counsel appeasement could read even a few of the articles by leading Japanese in the current Japanese magazines wherein their real desires and intentions are given expression, our peace-minded fellow countrymen would realize the utter hopelessness of a policy of appeasement.” Grew added a grim note: “In the meantime let us keep our powder dry and be ready—for anything.”

Nomura was prepared to look on the bright side when he sailed from Yokohama on January 23, 1941, to take up his new post. But his departure did not strike much optimism from the Japanese press. The next day commentator Teiichi Muto wrote: “The new ambassador to the United States, in fact, may be likened to a sailor who ventures to cross an ocean of angry waves in a tiny boat.”And about two weeks later the strongly nationalist Kokumin added this gloomy touch: “We offer our respect and gratitude to Ambassador Nomura with the same attitude as to soldiers going to the front with the determination to die.”

Nomura had been at sea only four days when Matsuoka sounded off ominously in a speech in Tokyo:

The Co-Prosperity Sphere in the Far East is based on the spirit of Hakko Ichiu, or the Eight Corners of the Universe under One Roof. . . . We must control the western Pacific. . . . We must request United States reconsideration, not only for the sake of Japan but for the world’s sake. And if this request is not heard, there is no hope for Japanese-American relations.

When Admiral Koshiro Oikawa became navy minister on September 4, 1940, he acknowledged, “Heavy are the responsibilities of the Navy which must be fully prepared to meet any emergency arising from the current trend of world events.” Oikawa had been a full admiral since 1939 and was one of Japan’s most able and distinguished naval officers. A large, dignified man of robust health, he had a broadly pleasant but unreadable face flanked by enormous ears. A man of few words, he expressed opinions rather than convictions.

He believed firmly in Japanese destiny and strongly supported the doctrine of southern expansion. He spoke of the war in China as a “sacred campaign.” He thought Japan might be “running some risk of picking Germany’s chestnuts out of the fire” because of the Tripartite Pact, but he believed that “America was so unlikely to go to war that the situation was fairly safe.” Even so, he preferred steady diplomatic and naval pressure to military action. Yet before the end of January 1941 Oikawa assured his countrymen that “the navy is prepared fully for the worst and . . . measures are being taken to cope with the United States naval expansion.”

By that time his head bulged with the weightiest of secrets. He knew a lot more than he was prepared to tell. Nor did he dare tell all he knew.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

£ 6.90 shipping from France to United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor:...

[( At Dawn We Slept: Untold Story of Pearl Harbor )] [by: Gordon W. Prange] [Dec-1991]

Seller: Ammareal, Morangis, France

Softcover. Condition: Bon. Ancien livre de bibliothèque. Traces d'usure sur la couverture. Ammareal reverse jusqu'à 15% du prix net de cet article à des organisations caritatives. ENGLISH DESCRIPTION Book Condition: Used, Good. Former library book. Signs of wear on the cover. Ammareal gives back up to 15% of this item's net price to charity organizations. Seller Inventory # E-190-651

Quantity: 1 available

At Dawn We Slept By Prange Gordon W Goldstein Donald M Dillon Katherine V

Seller: Bestsellersuk, Hereford, United Kingdom

Library Binding. Condition: Acceptable. Heavily creased and torn cover. Marks to cover and edge of pages. Bumped edges. Book is warped. No.1 BESTSELLERS - great prices, friendly customer service â" all orders are dispatched next working day. Seller Inventory # mon0000717420

Quantity: 1 available

At Dawn We Slept

Seller: Bookbot, Prague, Czech Republic

Softcover. Condition: Fine. Leichte Abnutzungen; Farbveranderung durch Alter/Sonne. Revisit the definitive book on Pearl Harbor in advance of the 78th anniversary (December 7, 2019) of the "date which will live in infamy" At 7:53 a.m., December 7, 1941, America's national consciousness and confidence were rocked as the first wave of Japanese warplanes took aim at the U.S. Naval fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor. As intense and absorbing as a suspense novel, At Dawn We Slept is the unparalleled and exhaustive account of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor. It is widely regarded as the definitive assessment of the events surrounding one of the most daring and brilliant naval operations of all time. Through extensive research and interviews with American and Japanese leaders, Gordon W. Prange has written a remarkable historical account of the assault that-sixty years later-America cannot forget. "The reader is bound to feel its power.It is impossible to forget such an account." --The New York Times Book Review "At Dawn We Slept is the definitive account of Pearl Harbor." --Chicago Sun-Times. Seller Inventory # 8e42f007-840f-4652-8a3c-7f9b3e05e40e

Quantity: 1 available

At Dawn We Slept

Seller: Hamelyn, Madrid, M, Spain

Condition: Bueno. : En este libro, Gordon W. Prange reconstruye escrupulosamente el ataque japonés a Pearl Harbor, desde su concepción hasta su ejecución. Basado en años de investigación y entrevistas, revela la verdadera razón del desastre estadounidense: la incredulidad ante la amenaza japonesa, que impidió que Estados Unidos prestara atención a las advertencias y provocó que los líderes ignoraran la evidencia de sus propias fuentes de inteligencia. Esta edición conmemorativa ofrece una visión profunda y detallada de uno de los eventos más trascendentales de la historia moderna. EAN: 9780140157345 Tipo: Libros Categoría: Historia Título: At Dawn We Slept Autor: Gordon W. Prange Editorial: Penguin Books Idioma: en Páginas: 912 Formato: tapa blanda. Seller Inventory # Happ-2024-11-27-068c3574

Quantity: 1 available

At Dawn We Slept : The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor; Revised Edition

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Reprint. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP89547747

Quantity: 2 available

At Dawn We Slept : The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor; Revised Edition

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Reprint. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 296145-6

Quantity: 1 available

At Dawn We Slept: Untold Story of Pearl Harbor

Seller: AwesomeBooks, Wallingford, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. At Dawn We Slept: Untold Story of Pearl Harbor This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # 7719-9780140157345

Quantity: 2 available

At Dawn We Slept: Untold Story of Pearl Harbor

Seller: Bahamut Media, Reading, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # 6545-9780140157345

Quantity: 2 available

At Dawn We Slept : The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK, Woodford Green, United Kingdom

Condition: good. May show signs of wear, highlighting, writing, and previous use. This item may be a former library book with typical markings. No guarantee on products that contain supplements Your satisfaction is 100% guaranteed. Twenty-five year bookseller with shipments to over fifty million happy customers. Seller Inventory # 493259-5

Quantity: 4 available

At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor; Revised Edition

Seller: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR001421607

Quantity: 4 available