This is an historical survey of the relationship between human and non-human, covering the major campaigns for reform and reviewing the shifts in attitude from the earliest times to the present day. The author's concept "speciesism" earns a niche in the philosophical debate that has characterized the movement over the last 15 years. The book describes this philosophical aspect and also puts forward psychological and sociological explanations. Richard Ryder describes the modernization of the RSPCA - the world's largest and oldest animal welfare organization - and the part he has played in turning animal liberation into the internationally significant media and political issue it has now become.

"The question is not, can they reason? Nor, can they talk? But can they suffer?" Jeremy Bentham's 1789 dictum lies at the heart of Richard D Ryder's very modern thinking. Psychologist, ethicist, historian: it is, however, a fourth dimension, his campaigning, which gets up the noses of those who embrace tradition and revere a self-defined notion of "natural" above Nature itself. Twenty years ago Ryder coined the term "speciesism" to describe the prejudicial attitudes of humans to nonhumans (he is inclined against the word "animals" when not inclusive of humans), controversially giving its similar status to racism and sexism.

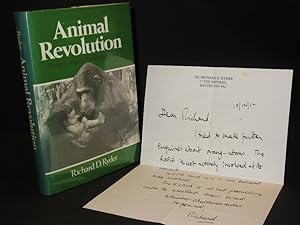

Animal Revolution was first published in 1989; this update, 10 years on, refines the theory to reflect 1990s developments, and on the whole the report card reads favourably, though naturally with scope for improvement.

The bulk of the text is a bestial concordance to the English and classical canon. Ryder strives to avoid a familiar catalogue of cruelties, but sets himself the harder task of weaving ideas from eclectic sources onto a framework of British, and to an increasing extent World, history. The detailing is serious but not po-faced--he relishes stories such as the sparrows excommunicated in 1499 for leaving their droppings on a church's pews--yet from 1824 onwards the narrative becomes more political with the forming of the Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Animals (among its founders was anti-slavery campaigner Sir William Wilberforce). A succession of setbacks and inertia, punctuated by legislation, finally erupted in the 1960s into radicalism, with which Ryder was heavily involved, taking things up to the modern day, where debate still rages as to the Society's purpose--rescuing kittens or lobbying politicians. The closing chapters, where Ryder outlines his personal philosophy of painism, are a model of gentle yet insistent didacticism drawn from reserves of ethical militancy, and it is to his credit that he prescribes understanding rather than absolutism when the fur starts to fly. Such compassionate reason, to apply his own words, is "easy to ridicule, hard to refute". --David Vincent