About this Item

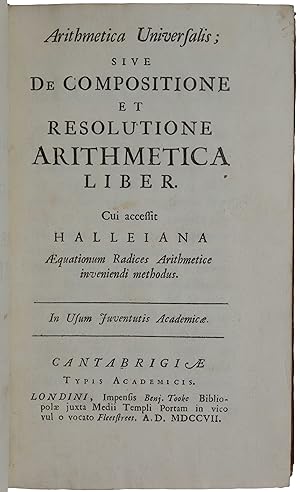

NEWTON S TREATISE ON ALGEBRA. First edition of Newton s treatise on algebra, or universal arithmetic, his "most often read and republished mathematical work" (Whiteside). "Included are Newton s identities providing expressions for the sums of the ith powers of the roots of any polynomial equation, for any integer i [pp. 251-2], plus a rule providing an upper bound for the positive roots of a polynomial, and a generalization, to imaginary roots, of René Descartes Rule of Signs [pp. 242-5]" (Parkinson, p. 138). About this last rule for determining the number of imaginary roots of a polynomial (which Newton offered without proof), Gjertsen (p. 35) notes: "Some idea of its originality … can be gathered from the fact that it was not until 1865 that the rule was derived in a rigorous manner by James Sylvester." Provenance: Jesuit College at Ghent (ink inscription Bibliotheca Collegii Gandavensis Soc[ietatis] Jesu. and shelfmark on title); extensive marginal annotations by a well-informed contemporary reader. This reader was possibly the English Jesuit Christopher Maier (1697-1767). Born in Durham, England, Maier entered the Society of Jesus in 1715. He taught at Liège, where he became interested in astronomy. In 1750, Maire was commissioned by Pope Benedict XIV to measure two degrees of the meridian from Rome to Rimini with fellow Jesuit Roger Boscovich, with a view to mapping the Papal States; in turn, they proved that the earth is an oblate spheroid, as Newton had proposed in Principia, publishing their results in Litteraria Expeditione (1755). Maier spent his final years at the English Jesuit College in Ghent. "In fulfillment of his obligations as Lucasian Professor, Newton first lectured on algebra in 1672 and seems to have continued until 1683. Although the manuscript of the lectures in [Cambridge University Library] carries marginal dates from October 1673 to 1683, it should not be assumed that the lectures were ever delivered. There are no contemporary accounts of them and, apart from Cotes who made a transcript of them in 1702, they seem to have been totally ignored. Whiteside (Papers V, p. 5) believes that they were composed over a period of but a few months during the winter of 1683-4" (Gjertsen, pp. 33-4). The course of lectures stemmed from a project on which Newton had embarked in the autumn of 1669, thanks to the enthusiasm of John Collins: the revision of Mercator s Latin translation of Gerard Kinckhuysen s Dutch textbook on algebra, Algebra ofte stel-konst (1661). Newton composed a manuscript, Observations on Kinckhuysen , in 1670 (see Whiteside, Papers II) and used it in the preparation of his lectures. He took the opportunity not only to extend Cartesian algebraic methods, but also to restore the geometrical analysis of the ancients, giving his lectures on algebra a strongly geometric flavor. "When Newton resigned his Lucasian professorship to his deputy William Whiston in December 1701, it was natural that the latter should wish to familiarize himself with the deposited lectures of his predecessor" (Whiteside, Papers V, p. 8). Whiston later claimed (in his Memoirs, London: 1749) that Newton gave him his reluctant permission to publish the lectures. Whiston arranged with the London stationer to underwrite the expense of printing the deposited manuscript and then subsequently, between September 1705 and the following June, corrected both specimen and proof sheets as they emerged from the University Press. The completed editio princeps finally appeared in May 1707, priced at 4s. 6d., without Newton s name on the title page, although references inside the work made no attempt to hide the author s identity. It included an appended tract by Halley on A new, accurate and easy method for finding the roots of any equations generally, without prior reduction (pp. 327-343). Publication of the work had been delayed by Newton, who complained that the titles and headings were not his and that it contained numerous m. Seller Inventory # 4639

Contact seller

Report this item

![]()