“No one can claim understanding of the late Middle Ages who has not read a Book of Hours in bed." - Christopher de Hamel, author of Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts

Books of Hours were medieval bestsellers. They were the first text read across Europe by people at every level of literacy. These devotional manuscripts, containing a daily routine of prayers for the reader to follow, reached a huge audience, more than any previously written text. Children were taught to read with Books of Hours. Repeated daily, the passages found in these books, usually in Latin, were committed to heart. Prayers on death, plague, warfare, travel, and bad weather were all found in Books of Hours.

Most rare book collectors now regard Books of Hours as beautiful illuminated picture-books, but they also transport us into the presence and intimate thoughts of people living 500 years ago.

The phrase Book of Hours comes from the eight “hours” of the day. These hours represent the regimented routine of daily prayer in monastic practice. At least in theory, monks or nuns would gather in chapel from break of day to late at night to pray the canonical hours every day at Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline.

Books of Hours adapt this monastic custom into a set of prayers for lay people at home or going about their daily routines at church or in town. Matins was at approximately 2am and Compline at the end of the day, around 7pm. Prime was at daybreak, Terce three hours later, and Sext around midday.

Central to these prayers is the Hours of the Virgin, which gained popularity through devotion to the Virgin. To understand the Hours of the Virgin, we must go back to the Annunciation (the moment Mary is informed by archangel Gabriel that she will give birth to God’s child). According to medieval tradition, the Virgin Mary was interrupted while kneeling in private, reading passages from her prayer book. She is shown praying in almost every Book of Hours.

One of the most famous examples of this scene appears in the Hours of Mary of Burgundy which shows Mary seated with her Book of Hours, surrounded by her gold jewelry and her pet dog in her lap. As she reads, she imagines the Virgin and Child in a church. This picture evokes simultaneously the preciousness of the book and the devotional act of its pious owner.

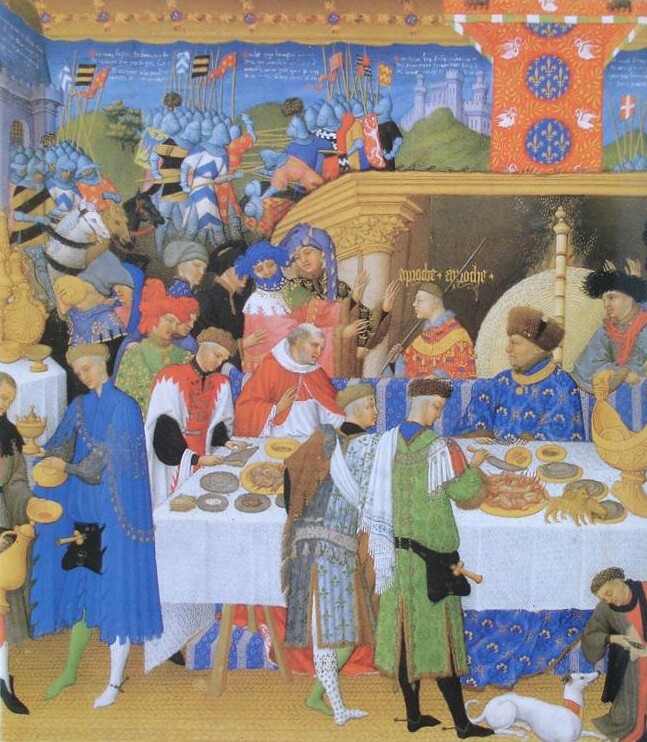

Books of Hours were frequently richly illustrated – they indeed served as picture-books then as well as now. A standard example might contain 10 to 12 pictures. Deluxe copies could include as many as 50 or 60 images, and the famous Très Riches Heures of the Duke of Berry has 131 full page illuminations.

The canonical picture cycle focused on the experiences of the Virgin Mary, which took place at the same time of day as that specific monastic hour. Mary went to stay with her cousin Elizabeth, pregnant with John the Baptist, just before dawn (the hour of Lauds); the Visitation. At daybreak, or Prime, the Birth of Christ took place in the stable in Bethlehem; the Nativity and so forth.

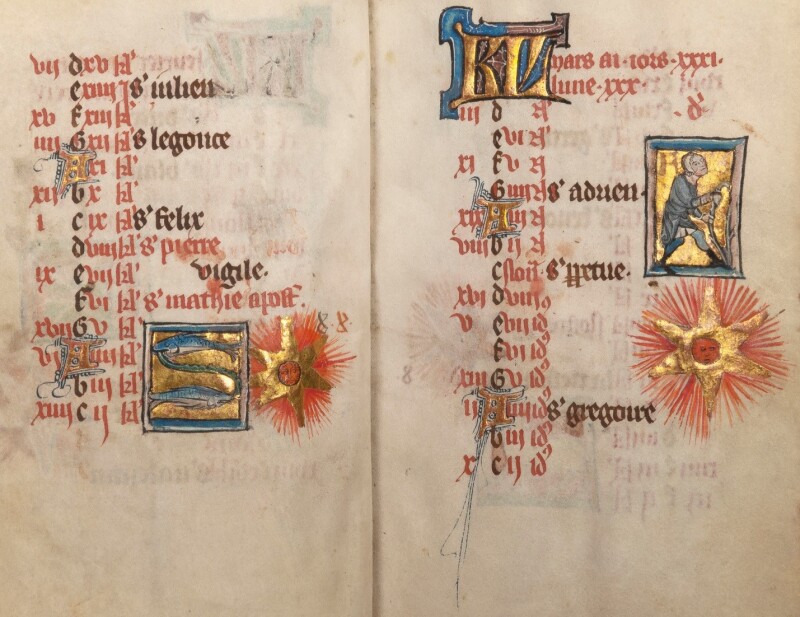

Lavish Books of Hours included Zodiac signs and the Labors of the Month as illustrations accompanying the calendar that prefaces nearly all examples. The text of the calendar lists birthdays of saints and other holidays (these “red letter days” were written in red ink). The accompanying pictures could show seasonal events such as pruning, planting, and harvesting. They remind us of a time when climate, the changing seasons, and local customs governed one’s days and months.

Below is another unusual example vividly illustrated the changing seasons, a calendar that shows an image of a golden sun with red rays low on the page in January and rising until June, after which it sinks lower and lower on the page until December. In a certain sense, a Book of Hours tells time before watches, alarm clocks, and cellphones.

Other sections are more closely tied to the text. Pictures of the saints illustrate the Suffrages, or the prayers medieval people recited to saints to help them in different circumstances. Saint Margaret helped with childbirth. Sebastian and Roch were used against the plague. People with dental problems prayed to Saint Apollonia. In the Hours of Catherine of Cleves (circa 1440), Apollonia is pictured holding a tooth.

Every saint had a function, and someone might choose to order a book filled with saints appropriate to him or her. King Charles VIII of France actually had few saints in his miniature, personalized Book of Hours although Saints Charlemagne and Louis appear as models of kingship.

Readers would also see Seven Penitential Psalms, showing King David, who composed the psalms. David could appear as an author portrait or ogling Bathsheba, one of the sins David committed for which these psalms were suitably remorseful.

A section called the Office of the Dead might show funeral services, a burial in a churchyard, or other examples of the suddenness of death.

Books of Hours came in all sizes. Charles VIII’s Book of Hours fits in the palm of one’s hand, and he might well have carried it with him, to parliament and even into battle. Other books are big and grand, more fitting to a library or private chapel. Some Books of Hours are modest, owned by people who probably had no other book in their household.

Every Book of Hours gives us a sense of ritual. We can imagine it being opened, cradled in the hand, carried about in a pouch suspended from a belt, and wrapped in velvet cloth. Few survive in their original bindings due to frequent use. Through the pictures, owners could share an experience with the Virgin, and admire the art of local painters, while also struggling with the words of the prayers, which were often used as a tool to teach reading. Books of Hours were personal, intimate, tactile, and visual.

Professional artisans in towns - not monks in monasteries - made Books of Hours. They were an urban product created as towns became more common in the later Middle Ages. Although the first Books of Hours date from about 1250, the 15th century represents the zenith of their popularity.

Specialized craftsmen used age-old recipes to prepare the pages of most Books of Hours from parchment or animal skin (cow, sheep, or goat, but most frequently cow), a support that has proved to be more stable and durable than paper, which only became common after the advent of printing. Painted with natural earthen or mineral colors, often composed of precious stones, like lapis lazuli, and genuine gold leaf, the pictures sparkle with reflected light, “illuminating” the page. This explains, in part, why they are as fresh today as they were when they were first created.

Books of Hours survive from every European country: France, the North and South Netherlands (today’s Holland and Belgium), England, Italy, and Germany. Except for those produced in the Netherlands, where religious reform generated a Dutch-language text, they are nearly always in Latin. Surviving Books of Hours from England are relatively rare, because the Reformation resulted in the destruction of many medieval Catholic manuscripts. French copies are most common with examples coming from Paris and the provincial regions.

Paris distinguished itself as the epicenter of printed Books of Hours, beginning in 1485 with an edition by Antoine Vérard. Approximately 1,775 separate editions of Books of Hours were printed between 1485 and 1600 by printers such as Gilles and Germain Hardouyn, Jean Pichore, Philippe Pigouchet, Simon Vostre, and others.

Small border vignettes of varying subjects (the Dance of Death, children’s games, the trials of Job, the Virtues and Vices, the Fifteen Last Things, etc.) became a selling point for successive editions. Many of these early printed Books of Hours resemble manuscripts - hand-ruled, rubricated (which refers to the use of elaborate capital letters), and hand-coloured, disguising the lines of the woodcut or wood engraving underneath a thick layer of paint.

Books of Hours began to decline in popularity in 1568 when Pope Pius V removed the obligation of the clergy to pray to the Office of the Virgin.

Scholars estimate that approximately 10,000 Books of Hours exist today in museums, libraries, and private collections. By calculating the survival rate, in the roughest sense possible, we can assume that one in 15 people owned a Book of Hours in France around 1500. This figure includes people from all levels of society, not just the middle and upper-classes in large urban areas. This is a staggering thought – even if it is guesswork. Medieval bestsellers indeed.

Large collections of Books of Hours are housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Other significant collections in North America include the Morgan Library & Museum in New York and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles. Sadly, they are not easy to see in museums, because viewings are often reserved for scholars. In Europe, the British Library maintains a public exhibition of Books of Hours. Facsimiles of some of the most famous Books of Hours are listed for sale on AbeBooks.

For further reading, start with two classics by Roger Wieck: Painted Prayers, The Book of Hours in Medieval and Renaissance Art and Time Sanctified, The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. To delve deeper, there is Books of Hours Reconsidered edited by myself and James Marrow. Videos, online courses, and podcasts abound.

Or acquire your very own manuscript Book of Hours and experience the magic of reading it at home in bed!

About the author: Sandra Hindman is a leading expert on medieval manuscripts and illumination. Professor Emerita of Art History at Northwestern University and owner of Les Enluminures, Sandra is author, co-author, or editor of more than 10 books, as well as numerous articles on history, illuminated manuscripts and medieval rings.