New Modification Cloud Method Determining by Millikan Robert (4 results)

Search filters

Product Type

- All Product Types

- Books (4)

- Magazines & Periodicals (No further results match this refinement)

- Comics (No further results match this refinement)

- Sheet Music (No further results match this refinement)

- Art, Prints & Posters (No further results match this refinement)

- Photographs (No further results match this refinement)

- Maps (No further results match this refinement)

- Manuscripts & Paper Collectibles (No further results match this refinement)

Condition Learn more

- New (No further results match this refinement)

- As New, Fine or Near Fine (No further results match this refinement)

- Very Good or Good (2)

- Fair or Poor (No further results match this refinement)

- As Described (2)

Binding

Collectible Attributes

- First Edition (3)

- Signed (No further results match this refinement)

- Dust Jacket (No further results match this refinement)

- Seller-Supplied Images (3)

- Not Print on Demand (4)

Language (1)

Price

- Any Price

- Under £ 20 (No further results match this refinement)

- £ 20 to £ 35 (No further results match this refinement)

- Over £ 35

Free Shipping

Seller Location

Seller Rating

-

A New Modification of the Cloud Method of Determining the Elementary Electrical Charge and the Most Probable Value of that Charge

Published by Taylor & Francis, London, 1910

Seller: Manhattan Rare Book Company, ABAA, ILAB, New York, NY, U.S.A.

First Edition

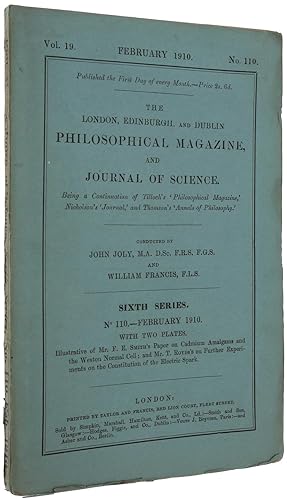

original wrappers. Condition: Very Good. First edition. FIRST EDITION IN ORIGINAL WRAPPERS of the account of Millikan's famous experiment, later known as the 'oil-drop experiment', in which he first provided the definitive proof that all electrical charges are exact multiples of a definite, fundamental value-the charge of the electron. Millikan's experiment is nowadays known as the 'oil-drop experiment' due to a later improvement by Millikan and his student Harvey Fletcher in 1910 - using oil in the cloud chamber - but it was in this paper (although water and alcohol were the liquids used) that Millikan first made precise measurements of the charge on single isolated droplets instead of as earlier just statistical averages on the surface of clouds of droplets. Although important, the fundamental breakthrough in Millikan's work was not his measurement of the actual value of the electron's charge (in fact he was as close to the correct value in this paper dated October 1909 as he was in the later oil experiment of 1910), but the fact that Millikan was able to produce, isolate, and observe single droplets with electrical charges, and show that repeated measurements of the charges always revealed exact integral multiples of one fundamental unity value. Previous experiments by Thomson and Wilson had in fact revealed the same value of the electron's charge as Millikan's experiment did but their determinations were based on statistical averages on the surface of large clouds of numerous water droplets and repeated measurements on the clouds gave fractional values of the electron's charge. This fact implied to some antiatomistic Continental physicists that it was not the constant of a unique particle but a statistical average of diverse electrical energies. However, in this 1909 experiment Millikan showed that his single droplets could not hold a fractional charge but always had a charge that was an exact integral multiple of an electron's charge (e.g., 2e, 3e, 4e, ?). In 1910 Millikan and Fletcher improved and simplified the whole experiment by using oil, mercury, and glycerin as liquids instead of water; they could now observe the droplets for several hours instead of just under one minute and also neglect having to compensate for the evaporation of the water and alcohol droplets. And thus the experiment became known as the 'oil-drop experiment', but the crucial breakthrough had already taken place in this 1909 experiment. In this paper Millikan emphasized that the very nature of his data refuted conclusively the minority of scientists who still held that electrons (and perhaps atoms too) were not necessarily fundamental, discrete particles. And he provided a value for the electronic charge which, when inserted in Niels Bohr's theoretical formula for the hydrogen spectrum, accurately gave the Rydberg constant-the first and most convincing proof of Bohr's quantum theory of the atom. In 1923 Millikan became the first American-born Nobel laureate for this work together with his1916 determination of Planck's constant on the basis of Einstein's theory of the photoelectric effect. Contained in: The Philosophical Magazine for February 1910, vol 19, no. 110, pp. 209-228. Octavo, original wrappers. London: Taylor & Francis, 1910. The entire issue offered here, uncut and unopened in the original blue printed wrappers (spine strip with some very good restoration, hardly noticable). Rare in wrappers in such good condition.

-

A New Modification of the Cloud Method of Determining the Elementary Electrical Charge and the Most Probable Value of that Charge

Published by Taylor & Francis, London, 1910

First Edition

Hardcover. modernphysics (illustrator). First edition. THE OIL DROP EXPERIMENT. A fine copy of Millikan's famous experiment, later known as the 'oil-drop experiment', in which he first provided the definitive proof that all electrical charges are exact multiples of a definite, fundamental valuethe charge of the electron. Millikan's experiment is nowadays known as the 'oil-drop experiment' due to a later improvement by Millikan and his student Harvey Fletcher in 1910 using oil in the cloud chamber but it was in this paper (although water and alcohol were the liquids used) that Millikan first made precise measurements of the charge on single isolated droplets instead of as earlier just statistical averages on the surface of clouds of droplets. Although important, the fundamental breakthrough in Millikan's work was not his measurement of the actual value of the electron's charge (in fact he was as close to the correct value in this paper dated October 1909 as he was in the later oil experiment of 1910), but the fact that Millikan was able to produce, isolate, and observe single droplets with electrical charges, and show that repeated measurements of the charges always revealed exact integral multiples of one fundamental unity value. Previous experiments by Thomson and Wilson had in fact revealed the same value of the electron's charge as Millikan's experiment did but their determinations were based on statistical averages on the surface of large clouds of numerous water droplets and repeated measurements on the clouds gave fractional values of the electron's charge. This fact implied to some antiatomistic Continental physicists that it was not the constant of a unique particle but a statistical average of diverse electrical energies. However, in this 1909 experiment Millikan showed that his single droplets could not hold a fractional charge of the electron's but always had a charge that was an exact integral multiple of the electron's (e.g., 2e, 3e, 4e, ). In 1910 Millikan and Fletcher improved and simplified the whole experiment by using oil, mercury, and glycerin as liquids instead of water; they could now observe the droplets for several hours instead of just under one minute and also neglect having to compensate for the evaporation of the water and alcohol droplets. And thus the experiment became known as the 'oil-drop experiment', but the crucial breakthrough had already taken place in this 1909 experiment. In this paper Millikan emphasized that the very nature of his data refuted conclusively the minority of scientists who still held that electrons (and perhaps atoms too) were not necessarily fundamental, discrete particles. And he provided a value for the electronic charge which, when inserted in Niels Bohr's theoretical formula for the hydrogen spectrum, accurately gave the Rydberg constantthe first and most convincing proof of Bohr's quantum theory of the atom. 'Among all physical constants there are two which will be universally admitted to be of predominant importance; the one is the velocity of light, which now appears in many of the fundamental equations of theoretical physics, and the other is the ultimate, or elementary, electrical charge, a knowledge of which makes possible a determination of the absolute values of all atomic and molecular weights, the absolute number of molecules in a given weight of any substance, the kinetic energy of agitation of any molecule at a given temperature, and a considerable number of other important physical quantities.' (First paragraph of the offered paper). In 1923 Millikan became the first American-born Nobel laureate for this work together with his1916 determination of Planck's constant on the basis of Einstein's theory of the photoelectric effect. Contained in: The Philosophical Magazine for February 1910, vol 19, no. 110, pp. 209-228. The entire issue offered here, uncut and unopened in the original blue printed wrappers (spine strip with some very good restoration, hardly noticible). 8vo (225 x 147 mm). Rare in such fine condition.

-

"A new modification of the cloud method of determining the elementary electrical charge and the most probable value of that charge," , in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine, Volume XIX, Sixth Series, 1910

Published by Taylor & Francis, 1910

Seller: JF Ptak Science Books, Hendersonville, NC, U.S.A.

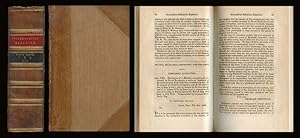

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. +++Millikan's First Published Steps Towards the Oil Drop Experiment of 1913 Indirectly Measuring the Charge of a Single Electron (1910)+++ Robert Millikan. "A new modification of the cloud method of determining the elementary electrical charge and the most probable value of that charge," in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine; London, Taylor & Francis, Volume XIX, Sixth Series, 1910, pp. 209-228, offered in the entire volume of 924pp, with 13 plates (some folding). Bound in black cloth with a red spine label, with heavily (professionally made) reinforced hinges. A big block of a book, very crisp, and in very nice sturdy shape. There is a remnant of a call card and a library name on a slip of paper half-attached to the front free endpaper, though this is the only mark I can find showing the history of ownership of the book. VERY GOOD copy. +++ "By 1909 Millikan was deeply involved in an attempt to measure the electronic charge. No one had yet obtained a reliable value for this fundamental constant, and some antiatomistic Continental physicists were insisting that it was not the constant of a unique particle but a statistical average of diverse electrical energies.[Millikan] launched his investigation with a technique developed by the British-born physicist H. A. Wilson; it consisted essentially of measuring, first, the rate at which a charged cloud of water vapor fell under the influence of gravity and then the modified rate under the counterforce of an electric field. Using Stokes's law of fall to determine the mass of the cloud, one could in principle compute the ionic charge. Millikan quickly recognized the numerous uncertainties in this technique, including the fact that evaporation at the surface of the cloud confused the measure of its rate of fall. Hoping to correct for this effect, he decided to study the evaporation history of the cloud while a strong electric Held held it in a stationary position. But when Millikan switched on the powerful field, the cloud disappeared; in its place were a few charged water drops moving slowly in response to the imposed electrical force. He quickly realized that it would be a good deal more accurate to determine the electronic charge by working with a single drop than with the swarm of particles in a cloud. Finding that he could make measurements on water drops for up to forty-five seconds before they evaporated. Millikan arrived at a value for e in 1909 which he considered accurate to within 2 percent. More important, he observed that the charge on any given water drop was always an integral multiple of an irreducible value. This result provided the most persuasive evidence yet that electrons were fundamental particles of identical charge and mass."-- Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, vol. 9, p 395. This was the first publication that would culminate in a final form in the of one of the most renowned scientific experiments of the 20th century, the oil-drop experiment of 1913 ("On the Elementary Electrical Charge and the Avogadro Constant", Phys. Rev. 2, 109 1 August 1913). "The first results came out in 1910, but the seminal work was a 1913 paper in the Physical Review. Millikan reported a value for the fundamental electric charge that was within half a percent of today's accepted value. The experiment helped earn Millikan a Nobel prize in 1923."--APS Physics Forums, "Focus: LandmarksMillikan Measures the Electron's Charge". Also in this volume are interesting papers by J.J. Thomson, J. Joly, C.V. Burton, Jean Perrin ("On the Charge of teh Electron"), A.S. Eve, H.A. Wilson ("On the relative Motion of the Earth and the Aether"), W.H. Eccles ("On Coherers"), Norman Campbell, Ernest Rutherford ("On the Action of Alpha Rays on Glass"), and numerous others, though to my eye the Millikan paper is the most significant.

-

A new modification of the cloud method of determining the elementary electrical charge and the most probable value of that charge, in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine, Volume XIX, Sixth Series, 1910, pp. 209-228

Published by Taylor and Francis, London, 1910

Seller: Atticus Rare Books, West Branch, IA, U.S.A.

First Edition

1st Edition. FIRST EDITION OF THE IMPORTANT PRECURSOR TO ROBERT MILLIKAN'S FAMOUS OIL DROP EXPERIMENT, THIS THE â??BALANCED-DROPLET' EXPERIMENT. In his autobiography, Millikan notes that this paper established the "first definite, sharp, unambiguous proof that electricity was definitely unitary in structure and that it only appeared in exact multiples of that unit." - a scenario that in essence made possible the measurement of the electrical charge. In this paper, Millikan makes "the important discovery that individual drops always carried an exact multiple of the smallest charge measured - this being the first accurate measurement of the charge of the electron" ( Davis, Science in the Making, Volume 3, 10-11). At the time of Millikan's writing, no one had yet obtained a reliable value for this fundamental constant, and some antiatomistic Continental physicists were insisting that it was not the constant of a unique particle but a statistical average of diverse electrical energies" (DSB, 9, pp. 395). "Millikan launched his investigation with a technique developed by the British-born physicist H. A. Wilson; it consisted essentially of measuring, first, the rate at which a charged cloud of water vapor fell under the counterforce of an electric field. Using Stokes's law of fall to determine the mass of the cloud, one could in principle compute the ionic charge. Millikan quickly recognized the numerous uncertainties in this technique, including the fact that evaporation at the surface of the cloud confused the measure of its rate of fall. Hoping to correct for this effect, he decided to study the evaporation history of the cloud while a strong electric field held it in a stationary position. But when Millikan switched on the powerful field, the cloud disappeared; in its place were a few charged water drops moving slowly in response to the imposed electrical force. "He quickly realized that it would be a good deal more accurate to determine the electronic charge by working with a single drop than with the swarm of particles in a cloud. Finding that he could make measurements on water drop s for up to forty-five seconds before they evaporated, Millikan arrived at a value for e in 1909 which he considered accurate to within 2 percent. More important, he observed that the charge on any given water drop was always an integral multiple of an irreducible value. This result provided that most persuasive evidence yet that electrons were fundamental particles of identical charge and mass" (ibid, 396). Here Millikan makes "the important discovery that individual drops always carried an exact multiple of the smallest charge measured - this being the first accurate measurement of the charge of the electron" ( Davis, Science in the Making, Volume 3, 10-11). Millikan recorded the "most probable value of the elementary electrical charge" to have "a weighted mean of 4.65 x 10 (-10) e.s.u. - a significant increase over previously determined values of e, but in excellent agreement with half the value Rutherford and Geiger had obtained for the charge on alpha particles in 1908" (Holton, 1978, 51; Davis, 11). Robert A. Millikan was an American physicist. He received the Nobel prize in 1923 "for his work on the elementary charge of electricity and on the photoelectric effect" (Nobel Portal). CONDITION & DETAILS: London: Taylor & Francis. (9 x 5.75 inches; 225 x 144mm). Complete. [4], viii, [924], 4. Thirteen plates and in-text illustrations throughout. Armorial bookplate on front pastedown (St. John's College, Oxford) and small stamp on the rear of the title page. No other library markings inside or out. Handsomely, solidly, and tightly rebound in three quarter brown calf over cloth boards; a line of slight toning on the front board (see scan); slight scuffing at the edges. Five gilt-ruled raised bands at the spine; gilt armorial devices in the compartments. Gilt-lettered red and black morocco spine labels. Bright and clean. Near fine condition.