David Littlejohn

I was born in San Francisco, as were my parents and grandparents. My grandfather’s grandfather came to California in 1850, along with a lot of other people. My children and grandchildren still live here. I’ve come to regard this state as a unique and explosively creative culture of its own, and have crafted my life so as to be able to live, work and write here--as often as not, writing about California.

I went to Berkeley to study architecture (it was nearby, and it was cheap). By my junior year, I discovered that I was a better writer than I was an architect. (I still travel to see and write about as many interesting buildings and cities as I can.) During those years, I also discovered what an exciting, tolerant, worldly place Berkeley was, and vowed to make it my home. I only went east to graduate school in order to get a position on the faculty at Cal--a dream job that I held for 35 years.

The English Department (where I started), and even more the Graduate School of Journalism (where I moved after six years), encouraged me to keep up my own writing. I had begun writing book reviews and articles for national magazines to pay graduate school bills. Back in Berkeley, I expanded my field to writing criticism of all the arts--I love good criticism, as much as I hate bad criticism--which led to ten years of television programs on KQED and the PBS network (268 programs) as their “Critic at Large.” At the same time, the university’s generous provisions for sabbatical and research leaves enabled me and my family to spend extended periods in England , France and Italy--I can handle French and Italian, and am working on Russian. During these leaves, and the long summer breaks, I was able to write most of my 14 books, eleven of them (including two novels) for commercial publishers, the other three privately printed.

One of the great things about teaching in Berkeley’s journalism school was that I was able to combine, as Robert Frost once wrote, my vocation with my avocation. As a writer, I was writing critical reviews, crafting interviews and profiles of artists and art institutions (from jazz clubs to opera companies), and trying to turn my nonfiction reporting into something like literature, in the Dickens-to-Didion tradition. At the same time, I was paid to teach courses in The Critical Review, Reporting on Cultural Events, and Reporting as Literature. Trying to turn good writers into better writers for 35 years was not only a rewarding challenge in itself. It also forced me to be more careful, honest and conscientious as a writer myself. I also learned to love collaboration. My late wife Sheila (who was English) took all the great pictures for our book on English country houses. My last (and best) graduate seminar wrote all of the chapter/essays for our book on Las Vegas: my job was just to whip them along, edit edit edit, and write the bookending intro and afterword. Both these projects ended up as books published by Oxford University Press.

I’m now retired from teaching--35 years was enough, and my physical strength was giving out--but not from writing. I still try to do my more-or-less monthly “reports from California” for the Wall Street Journal (I admire their reporters’ industry and integrity, and the arts editor’s high standards--if not their editorial-page politics), write articles and introductions when asked by good friends, and have finished two (as yet unpublished) books since my retirement.

For me, writing is like breathing. When you stop it, you die. I broke my neck diving in a lake in the Sierra at 14, and had to walk around the world on crutches after that. Nerves and muscles took another dip later in life, and I’ve been using a wheelchair for the past ten years. There may be a book in that story also, if I ever achieve sufficient detachment to tell it straight.

Popular items by David Littlejohn

View all offers-

The Ultimate Art – Essays Around & About Opera: Essays Around and About Opera

Littlejohn, David

Item prices starting from

View 47 offers£ 4.26

-

The Fate of the English Country House

Littlejohn, David

Item prices starting from

View 70 offers£ 5.74

-

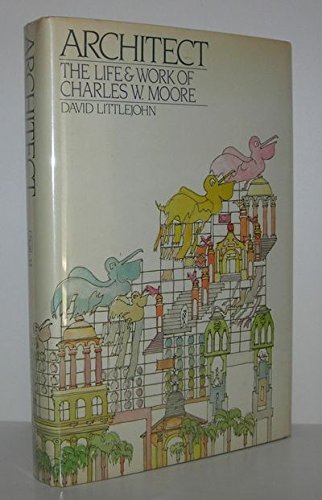

Architect: The Life and Work of Charles W. Moore

Littlejohn, David.

Item prices starting from

View 19 offers£ 7.47

-

-

-

-

-

The Big One: A Story of San Francisco

Littlejohn, David

Item prices starting from

View 4 offers£ 16.34

You've viewed 8 of 12 titles