About this Item

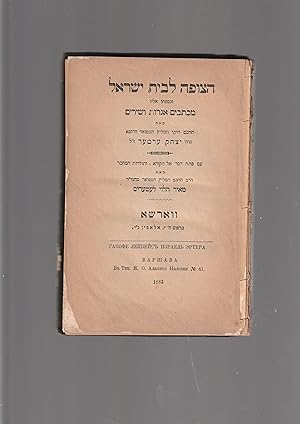

In Hebrew. XX, 142 pages. 198 x 132 mm. Includes a biography of the author. Blank front endpaper has rubber stamp impression of early owner: "Lev Genikhovich Spiegel 11 sept. [18]86". Boards and a few leaves detached. Yellowed and brittle. Isaac Erter was a Polish-Jewish satirist. He spent the first part of his life in hardships, spent many years associated with the Hasidim, settled at Lemberg; and through the efforts of some of his friends, Rapoport, Krochmal, and others, he obtained pupils he instructed in Hebrew and other subjects. But after 3 years (1813-1816), Jacob Orenstein, chief rabbi of Lemberg, learned that Erter and his disciples were pursuing secular subjects, he put a ban on them all. Deprived thus of his pupils, the only means of his subsistence, he moved to neighboring Brody, where he struggled for a while, until he decided to study medicine. In 1825 he enrolled in the University of Budapest, studied medicine for five years and passing all the examinations, he then practiced medicine in various Galician towns, including Brody, where he made himself especially popular among the poor and needy, who found in him a kindly benefactor. He composed a number of Hebrew satires, giving him a prominent place among modern Hebrew satirists. For a time he edited the Hebrew periodical "He-Halutz," which promoted culture and enlightenment among the Galician Jews. The periodical also advocated the establishment in Galicia of agricultural colonies for the employment and benefit of young Jews. Erter's fame rests chiefly on his 6 satires, published under the title "Ha-Tzofeh le-Bet Yisrael" (Vienna, 1858; 1864): "Mozne Mishqal"; "Ha-Tzofeh be-Shubo mi-Karlsbad"; "Gilgul ha-Nefesh"; "Tashlikh"; "Telunat Sani we-Sansani we-Samangaluf"; "?asidut we-?okmah." The most attractive of these is "Gilgul ha-Nefesh," the story of the many adventures of a soul during a long earthly career; how it frequently passed from one body into another, and how it had once left the body of an ass for that of a physician. The soul gives the author the following six rules, by observing which he might succeed in his profession: 1. Powder your hair white, and keep on the table of your study a human skull and some animal skeletons. Those coming to you for medical advice will then think your hair has turned white through constant study and overwork in your profession. 2. Fill your library with large books, richly bound in red and gold. Though you never even open them people will be impressed with your wisdom. 3. Sell or pawn everything, if that is necessary, to have a carriage of your own. 4. When called to a patient pay less attention to him than to those about him. On leaving the sick-room, assume a grave face, and pronounce the case a most critical one. Should the patient die, you will be understood to have hinted at his death; if, on the other hand, he recovers, his relations and friends will naturally attribute his recovery to your skill. 5. Have as little as possible to do with the poor; as they will only send for you in hopeless and desperate cases you will gain neither honor nor reward by attending them. Let them wait outside your house, that passers may be amazed at the crowd waiting patiently to obtain your services. 6. Consider every medical practitioner as your natural enemy, and speak of him always with the utmost disparagement. If he be young, you must say he has not had sufficient experience; if he be old, you must declare that his eyesight is bad, or that he is more or less crazy, and not to be trusted in important cases. When you take part in a consultation with other physicians, you would act wisely by protesting loudly against the previous treatment of the case by your colleagues. Seller Inventory # 015583

Contact seller

Report this item

![]()