Items related to Theories of Resistance: Anarchism, Geography, and the...

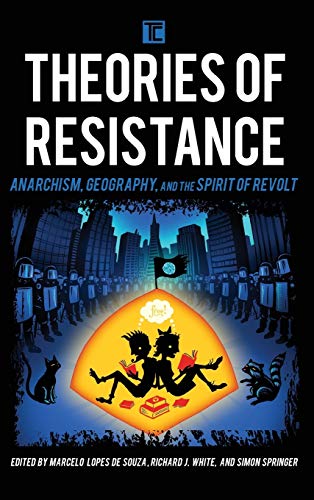

Theories of Resistance: Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt (Transforming Capitalism) - Hardcover

Synopsis

Space is never a neutral 'stage' on which social actors play their roles, sometimes cooperating with each other, sometimes struggling against each other. Space has multiple and complex functions in the development of social relations, it is a reference for identity-building, a material condition for existence, and an instrument of power. This book explores the ways in which space has been used for resistance, especially in left-libertarian contexts. From the early anarchist organizing efforts in the 19th century to the contemporary social movements of the Mexican Zapatistas, the chapters examine a range of cases to illustrate both the limits and potentialities of utilizing space within anarchist practice. By theorizing the production of anarchist spaces, the book aims to foster new geographical imaginations that energetically cultivate alternative practices to challenge the status quo. It shows that spatial re-organization, spatial practices and spatial resources are also a basic condition for human emancipation, autonomy and freedom.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Marcelo Lopes de Souza is Professor of Geography at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil. Richard J. White is Reader in Economic Geography at Sheffield Hallam University, UK. Simon Springer is Associate Professor of Geography at University of Victoria, Canada.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Theories of Resistance

Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt

By Marcelo Lopes de Souza, Richard J. White, Simon SpringerRowman & Littlefield International, Ltd.

All rights reserved.

Contents

Acknowledgements, ix,

Introduction: Subverting the Meaning of 'Theory' Marcelo Lopes de Souza, Richard J. White, and Simon Springer, 1,

1 'Libertarian,' Libertaire, Libertario ...: Conceptual Construction and Cultural Diversity (and Vice Versa) Marcelo Lopes de Souza, 19,

2 Non-Domination, Governmentality and the Care of the Self Nathan Eisenstadt, 27,

3 Post-Statist Epistemology and the Future of Geographical Knowledge Production Gerónimo Barrera de la Torre and Anthony Ince, 51,

4 What Do We Resist When We Resist the State? Erin Araujo, 79,

5 Towards a Theory of 'Commonization' Nick Clare and Victoria Habermehl, 101,

6 'Feuding Brothers'?: Left-Libertarians, Marxists and Socio-Spatial Research at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century Marcelo Lopes de Souza, 123,

7 The Citizen and the Nomad: Bookchin and Bey on Space and Temporality Benjamin J. Pauli, 155,

8 Swimming Against the Current: Towards an Anti-Colonial Anarchism in British Columbia, Canada Vanessa Sloan Morgan, 177,

9 Anarchy, Space, and Indigenous Resistance: Developing Anti-Colonial and Decolonizing Commitments in Anarchist Theory and Practice Adam Gary Lewis, 207,

10 Celebrating the Invasive: The Hidden Pleasures and Political Promise of the Unwanted Nick Garside, 237,

Index, 253,

About the Contributors, 257,

CHAPTER 1

'Libertarian,' Libertaire, Libertario ...

Conceptual Construction and Cultural Diversity (and Vice Versa)

Marcelo Lopes de Souza

This short chapter was originally intended as a section (titled 'For the Sake of Clarity (and Justice): Who Are the '(Left-)Libertarians'?) of my chapter '"Feuding Brothers"? Left-Libertarians, Marxists and Socio-Spatial Research at the Beginning of the Twenty-First Century' (see this volume). Following a suggestion made by our publishers, however, I decided to make that other chapter more concise by means of transforming this conceptual discussion into an autonomous piece. Considering the importance of this terminological/ conceptual debate beyond the borders of the specific problem analysed in that text on the complex and difficult relationship between (left-)libertarians and Marxists, an autonomous existence of this piece can be of advantage by means of shedding light upon a crucial challenge in terms of intercultural communication inside the (left-)libertarian field.

Maybe it is a surprise for some, but 'libertarian' is an astonishingly polysemous word. For several reasons, this is not a minor question, and several misunderstandings have arisen from this polysemy — a phenomenon largely connected with cultural diversity. Although it is certainly not the case of simply advocating some culturally embedded discursive context detrimental to others, it is surely important to clarify what different authors and peoples/ (political) cultures understand and have understood as 'libertarian.' This task is necessary not only because the meaning of this word has been very often reduced to anarchism, especially to what I have called 'classical anarchism'— an oversimplified interpretation that must be challenged — but also because this term has gotten a peculiar meaning among Anglophone people, particularly in the United States. This U.S.-specific meaning strongly contrasts with the one that has shaped the continental European (French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese and even German) and Latin American traditions.

* * *

The French word libertaire was coined by writer and poet Joseph Déjacque in a letter to Pierre-Joseph Proudhon written in 1857, in which he criticizes the latter for the scandalously misogynous aspects of his thought (see Déjacque 2014). Since then, 'anarchist' and 'libertarian' are terms which have inextricably connected with each other to the point of being regarded practically as synonymous in almost all countries.

A broader, more plastic view, however, is possible — and indeed convenient or even necessary. In my works (see, for instance, Souza 2012a, 2012b, 2012c, 2014, and 2015), the adjective (left)libertarian covers a wider spectrum of political-philosophical streams and types of political and spatial practice than that set of authors, movements and experiences directly related to anarchism in a strict sense. In fact, it covers the set of approaches to society which historically evolved within the framework of what can be called a 'two-front-war,' in the context of which (left-)libertarians have theoretically and politically fought simultaneously against capitalism and against 'authoritarian' approaches to socialism (above all, Marxism's statism and centralism). In spite of the essential convergence of all left-libertarian positions within the framework of this 'two-front-war,' the aforementioned set of approaches has become increasingly heterogeneous since the middle of the twentieth century, as several conceptual and theoretical aspects and premises shared by nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century anarchists 1 have begun to be criticized or strongly relativized from new libertarian perspectives. In other words, left-libertarian thought and praxis should not be taken as synonymous with anarchism in a strict sense which I have proposed calling classical anarchism (whose maximum influence stretched from the second half of the nineteenth century to the 1930s); we must also include in the left-libertarian 'galaxy' the approaches that have been developed since the second half of the twentieth century and which tacitly or explicitly challenge the classical heritage in various degrees, mainly encompassing the several forms of neo-anarchism (e.g., Murray Bookchin's 'libertarian municipalism') and autonomism (brilliantly represented by Cornelius Castoriadis's 'projet d'autonomie').

As I already pointed out in Souza (2014), classical anarchism, regardless of its enduring importance as a source of inspiration in some respects, has also presented several limitations, which were stressed for instance by both U.S.-American neo-anarchist Murray Bookchin and Graeco-French autonomist Cornelius Castoriadis many years ago (from partly convergent and partly different perspectives, but always from an essentially [left-]libertarian viewpoint, as both were at the same time radically anti-capitalist and consistently anti-Marxist minded). One of their objections is that one related to the understanding of concepts such as power, law and government. In contrast to classical anarchists, who typically used the term 'power' as synonymous with something necessarily bad, Bookchin refused to reduce power to heteronomous power (i.e., structural power asymmetry, control, verticality). Symptomatically, among his criticisms against Foucault was precisely the fact that the latter assigned in a way more or less similar to classical anarchists' style a pejorative connotation to the word which corresponds, in Bookchin's (1995, 228–29) opinion, to a pernicious narrow-mindedness. Castoriadis (1983) expressed a similar disapproval of this kind of conceptualization typical of classical anarchism, and in a number of works he showed the reasons why concepts like 'power' and 'law' deserve to be understood in a non-reductionist way — a position that far from being detrimental to a radically anti-capitalist approach in fact enhances a deeper grasping of the circumstances under which human emancipation is realistically possible (see Castoriadis 1983, 1990, 1996). Bookchin also pleaded for a broader, more flexible understanding, admonishing orthodox anarchists for making the mistake of reducing the meaning of concepts such as 'government' and 'law' to the state apparatus.

Besides all that, there is a further, broader problem that Bookchin apparently did not become aware of: the exaggerated attachment of classical anarchism to physis (i.e., Greek 'nature' in the strict sense of 'first nature,' erste Natur) — in other words, its 'naturalism' — and its underestimation or even its relative neglect of nomos (i.e., Greek 'law,' broadly understood as rules, norms, habits and customs, or as the proper domain of society and culture in an even broader sense). It is not difficult to see that this problem conditioned several of classical anarchism's limitations. Convinced that the 'laws of nature' decisively influence human behaviour and condition human possibilities from the very beginning, classical anarchists typically believed 'harmony' and 'progress' could be achieved through learning and respecting these 'laws'; society should, hence, adjust to them, and the main problem of state power, laws and authority (or, in direct spatial terms, state boundaries and socio-spatial identities conditioned by them) would lie in the supposed fact that they were not 'natural' enough. This kind of 'naturalizing' of society, which actually goes far beyond vulgar 'environmental determinism,' can be clearly illustrated by Piotr Kropotkin's case. For him, 'mutual aid' among human beings is as much a fact of 'human nature' as it is a component of nature as a whole. Considering this, it is not a surprise that Kropotkin explicitly rejected dialectics, advocating instead positivism and championing the inductive method of experimental sciences within the framework of an approach to nature and society according to which science and natural science are ultimately synonymous. This 'naturalizing' way of thinking, systematically defended by Kropotkin but strongly present in most of classical anarchism altogether, is also a factor behind beliefs such as those related to the teleology of 'progress,' the optimistic (and we should add unhistorical) view of an immutable and essentially good 'human nature' and the belief according to which 'power' and 'law' are always to be seen as something negative — the alternative being a society supposedly based on 'spontaneity,' and it is clear that this 'naturalistic' ideology prevented classical anarchists from seeing that rules (even self-imposed and self-managed ones, that is autonomy [autos + nomos]) are unavoidable, and that explicit, easily and regularly changeable rules are preferable than the insistence on a metaphysical, unrealistic state of 'pure spontaneity.' It is interesting to notice that even Élisée Reclus, a very sophisticated author in several respects, had his creativity restricted by the chains of a largely (though increasingly relativized throughout his life) physis-oriented approach.

Murray Bookchin had shown reservations towards the nostalgic traditionalism of many anarchists. In a very symptomatic way, at the beginning of a lecture in 1980, he announced his intention with that speech: 'My remarks are intended to emphasize the extreme importance today of viewing Anarchism in terms of the changing social contexts of our era — not as an ossified doctrine that belongs to one or another set of European thinkers, valuable as their views may have been in their various times and places' (Book- chin 2012, np). As far as Castoriadis is concerned, his criticisms against (classical) anarchism date back to the late 1940s and comprise objections against anarchism's individualism (a real problem in many cases, but which was grossly oversimplified and exaggerated by Castoriadis) and against the typically reductionist understanding of concepts such as 'power' and 'law.' Bookchin and Castoriadis, on the one hand, and also many social movements such as Mexican Zapatistas, on the other, illustrate the necessity of widening the scope of the term 'libertarian' in order to do justice to contemporary reflections and forms of emancipatory praxis.

* * *

Last but not least, a further clarification is very much needed, envisaging U.S.-American readers. While 'libertarian' is a word inextricably connected with leftist traditions in all Latin languages (and even in German), it has often a different meaning in English, particularly in the United States.

The English adjective libertarian was apparently coined at the end of the eighteenth century by late-Enlightenment freethinkers, initially meaning just an anti-deterministic belief in free will. However, while in France libertaire eventually became strongly associated with anarchism, in the course of time a quite different meaning has developed on the other side of the Atlantic. In the United States, where political-cultural ideas and values have been inextricably conditioned by a long tradition of individualism and privatism, the term libertarian often designates a kind of ultraliberal ideology and the defence of a 'minimum state' commonly in the absence of any trace of criticism against possessive individualism and capitalism, as exemplified by bizarre phenomena such as 'anarcho-capitalism' and the Libertarian Party (formed in 1971). As a consequence, it is usually necessary in the United States to differentiate between 'right-libertarian' and 'left-libertarian' — a precaution that is virtually superfluous or even confusing in most other countries. In fact, the historical role of individualism and privatism in U.S.- American political culture has been so overwhelming that even anarchism in a strict sense has been often represented in that country by 'individualist anarchists' like Benjamin Tucker and, to a large extent, even Emma Goldman. Be that as it may, it is important to notice that there have been outstanding Anglophone thinkers and activists who have always used the term in its original, left-libertarian meaning, such as George Woodcock, Murray Bookchin, and Noam Chomsky.

In light of all the above considerations, from a Latin American (or continental European) perspective, the struggle over the meaning of the term 'libertarian' is worthwhile.

CHAPTER 2Non-Domination, Governmentality and the Care of the Self

Nathan Eisenstadt

Non-domination has been powerful concept for contemporary anarchist scholarship (Newman 2001; May 1994, 2007; Gordon 2008, 2010). It is attentive to multiple and intersecting modes of oppression that delimit possibilities for human becoming. It refuses a hierarchy of oppressions, and thus avoids privileging a particular mode revolutionary subjectivity as primary. And it links the freedom of one to the freedom of all. Domination, May argues, is but one deleterious effect of power — one that arises in situations of inequality (2007, 21; 2008). Thus, non-domination requires a maximal equality of power relations — it renders freedom and equality inseparable while avoiding defining freedom through recourse to an essentialized human subject. The contemporary preoccupation with non-domination has its roots in the thought of finde-siècle and early twentieth-century anarchists like Bakunin, Kropotkin, Reclus, Goldman, Landauer and others — who were famously attentive to the inseparability of freedom from equality and to the diffuse and situated character of power whether manifested in state, religion, class relations, the family unit, gender norms or any other hierarchically organized social form (Antliff 2007; Franks 2007).

In this chapter I take issue with what is arguably the dominant conceptualization of non-domination within contemporary anarchist movements — non-domination as empowerment as advanced by Gordon (2008). I argue that while this concept is useful in attentiveness to intersectionality and its linking of freedom with equality, it lacks an account of the disciplinarity of the call to empower others and thus of the constitutive character of power. In so doing, non-domination-as-empowerment reestablishes the idea of a sovereign subject, and thus, the humanist essentialism that contemporary scholars, in particular, have been at pains to avoid. In the second part of the chapter I draw on governmentality scholarship to account for the disciplinary character of anarchism's 'will to empower' others. However, while governmentality scholarship is useful, I argue that it lacks the tools to differentiate between liberal and illiberal forms of empowerment and thus to articulate a more liberating mode of governing through freedom, despite its crypto-normative (Heyes 2007, 11) claim that the freedom we are invited to embrace under liberalism is insufficiently liberating. In order to articulate a more liberating mode of governing through freedom without recourse to the liberal subject, I draw together Foucault's later work on the care of the self, late twentieth-century Black Feminist critique, and contemporary anarchist anti-oppressive practices. The claims I make are based on a four-year autoethnographic engagement of two anarchist social centres and associated projects in Bristol, England.

NON-DOMINATION AND THE CONSTITUTIVE CHARACTER OF POWER

The idea of non-domination as form of empowerment is rooted in eco-feminist-activist-writer Starhawk's proposal for a three-fold schematic for understanding power (Starhawk 1987). This differentiates between 'power-from-within' as personal capacity and 'inner strength'; 'power-over' as power wielded so as to dominate the will of another; and 'power-with' as power wielded non-coercively amongst people who see themselves as equals. Holloway (2002) uses this schematic, recasting it through Marx's theory of alienation and simplifying 'power-from-within' to 'power-to' as the capacity to affect reality. In Capitalism, Holloway argues, the worker's 'power-to' is sold as labour-power, transforming it into an owner's 'power-over,' thereby alienating human begins from their capacity to do (ibid., 36, 37). However, as Gordon points out, this fails to account for inequalities of 'power-to' in non-capitalist relations, such as within anarchist groups (2010, 44). In a brilliant and influential book based on extensive empirical research, Gordon (2008) articulates and re-confirms what is arguably the dominant understanding of power in contemporary anarchist praxis. This draws on Starhawk's three-fold framework to analyse the sources of inequalities of 'power-to' within anarchist groups and expose the tension between overt and covert forms of power. Through signalling the possibility of productive power (as 'power-to' and 'power-with'), this framing seems to avoid an account of power as a 'constitutive outside' from a benign human subject and is attentive to the multiple and intersecting forms that oppression can take.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Theories of Resistance by Marcelo Lopes de Souza, Richard J. White, Simon Springer. Copyright © 2016 Marcelo Lopes de Souza, Richard J. White, and Simon Springer. Excerpted by permission of Rowman & Littlefield International, Ltd..

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsBuy New

View this itemFREE shipping from U.S.A. to United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Theories of Resistance: Anarchism, Geography, and the...

THEORIES OF RESISTANCE: ANARCHISM, GEOGRAPHY, AND THE SPIRIT OF REVOLT

Seller: Basi6 International, Irving, TX, U.S.A.

Condition: Brand New. New. US edition. Expediting shipping for all USA and Europe orders excluding PO Box. Excellent Customer Service. Seller Inventory # ABEJUNE24-362302

Quantity: 1 available

Theories of Resistance : Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK, Woodford Green, United Kingdom

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 24321722-n

Quantity: Over 20 available

Theories of Resistance

Seller: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, United Kingdom

HRD. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # CW-9781783486663

Quantity: 15 available

Theories of Resistance: Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt (Transforming Capitalism)

Seller: ALLBOOKS1, Direk, SA, Australia

Seller Inventory # SHUB362302

Quantity: 1 available

Theories of Resistance: Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt (Transforming Capitalism)

Seller: Ria Christie Collections, Uxbridge, United Kingdom

Condition: New. In. Seller Inventory # ria9781783486663_new

Quantity: Over 20 available

Theories of Resistance : Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt

Seller: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 24321722-n

Quantity: Over 20 available

Theories of Resistance : Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt

Seller: GreatBookPricesUK, Woodford Green, United Kingdom

Condition: As New. Unread book in perfect condition. Seller Inventory # 24321722

Quantity: Over 20 available

Theories of Resistance (Hardcover)

Seller: CitiRetail, Stevenage, United Kingdom

Hardcover. Condition: new. Hardcover. Space is never a neutral stage on which social actors play their roles, sometimes cooperating with each other, sometimes struggling against each other. Space has multiple and complex functions in the development of social relations, it is a reference for identity-building, a material condition for existence, and an instrument of power.This book explores the ways in which space has been used for resistance, especially in left-libertarian contexts. From the early anarchist organizing efforts in the 19th century to the contemporary social movements of the Mexican Zapatistas, the chapters examine a range of cases to illustrate both the limits and potentialities of utilizing space within anarchist practice. By theorizing the production of anarchist spaces, the book aims to foster new geographical imaginations that energetically cultivate alternative practices to challenge the status quo. It shows that spatial re-organization, spatial practices and spatial resources are also a basic condition for human emancipation, autonomy and freedom. Part two of an innovative trilogy on anarchist geography, this text examines how we can better understand the ways in which space has been used for resistance Shipping may be from our UK warehouse or from our Australian or US warehouses, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781783486663

Quantity: 1 available

Theories of Resistance : Anarchism, Geography, and the Spirit of Revolt

Seller: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: As New. Unread book in perfect condition. Seller Inventory # 24321722

Quantity: Over 20 available

THEORIES OF RESISTANCE ANARCHICB

Seller: moluna, Greven, Germany

Gebunden. Condition: New. Part two of an innovative trilogy on anarchist geography, this text examines how we can better understand the ways in which space has been used for resistanceÜber den AutorMarcelo Lopes de Souza is Professor of Geography at the . Seller Inventory # 43952359

Quantity: Over 20 available