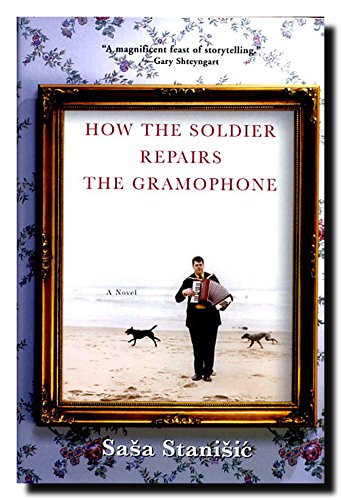

Items related to How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Synopsis

<div>For young Aleksandar Krsmanoviæ, his grandfather Slavko’s credo--“the most valuable gift of all is invention, imagination is your greatest wealth”--endows life in Višegrad, Bosnia-Herzegovina with a mythic quality, a kaleidoscopic brilliance. So when his grandfather dies suddenly, Aleks summons this gift of storytelling to see him through his grief. It is a gift he will have to call on again when soldiers transform Višegrad--a town previously unconscious of racial and religious divides--into a nightmarish landscape of terror and violence. Though Aleks and his family flee to Germany, he is haunted by his past, and especially by Asija, the mysterious girl he tried to save. Desperate to learn of her fate, he sends manic, anguished letters out into the abyss, again turning to language to conjure all that he’s had to forfeit--his homeland, his mother tongue, his innocence. Beneath the infectious vibrancy of Stanišiæ’s voice is a sweetness and pathos that will haunt the reader long after the book ends. Powerful, vivid, funny, and devastating, <i>How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone</i> captures the catastrophe of war through a child’s eyes and shows how words have the ability to mend what is broken and resurrect what is lost.</div>

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

How the Soilder Repairs the Gramophone

By Sasa StanisicGrove Press

Copyright © 2006 Luchterhand Literaturverlag, MunchAll right reserved.

ISBN: 978-0-8021-1866-0

Contents

How long a heart attack takes over a hundred metres, how heavy a spider's life weighs, why my sad man writes to the cruel river, and what magic the comrade-in-chief of all that's unfinished can work.....................1How sweet dark red is, how many oxen you need to pull down a wall, why Kraljevic Marko's horse is related to Superman, and how war can come to a party.....................................................................20Who wins when Walrus blows the whistle, what a band smells of, when you can't cut fog, and how a story leads to an agreement...............................................................................................40When flowers are just flowers, how Mr Hemingway and Comrade Marx feel about each other, who's the real Tetris champion, and the indignity suffered by Bogoljub Balvan's scarf..............................................46When something is an event, when it's an experience, how many deaths Comrade Tito can die, and how the once famous three-point shooter gets behind the wheel of a Centrotrans..............................................53What Milenko Pavlovic, known as Walrus, brings back from his wonderful trip, how the station-master's leg loses control of itself, what the French are good for, and why we don't need quotation marks.....................68Where bad taste in music gets you, what the three-dot-ellipsis man denounces, and how fast war moves once it really gets going.............................................................................................73What we play in the cellar, what the peas taste like, why silence bares its fangs, who has the right sort of name, what a bridge will bear, why Asija cries, how Asija smiles..............................................82How the soldier repairs the gramophone, what connoisseurs drink, how we're doing in written Russian, why chub eat spit, and how a town can break into splinters............................................................94Emina carried through her village in my arms...............................................................................................................................................................................10526 April 1992..............................................................................................................................................................................................................1079 January 1992.............................................................................................................................................................................................................11017 July 1993...............................................................................................................................................................................................................1138 January 1994.............................................................................................................................................................................................................116Hi, who? Aleksandar! Hey, where are you calling from? Oh, not bad! Well, lousy really, how about you?......................................................................................................................11816 December 1995...........................................................................................................................................................................................................120what I really want.........................................................................................................................................................................................................1221 May 1999.................................................................................................................................................................................................................124Aleksandar, I really, really want to send you this package.................................................................................................................................................................128When everything was all right. By Aleksandar Krsmanovi, with a foreword by Granny Katarina and an essay for Mr Fazlagi.....................................................................................................13111 February 2002...........................................................................................................................................................................................................180I'm Asija. They took Mama and Papa away with them. My name means something. Your pictures are horrible.....................................................................................................................181Out of three hundred and thirty Sarajevo numbers rung at random, about every fifteenth has an answering machine............................................................................................................188What makes the Wise Guys wise, how much you ought to bet on your own memory, who is found and who is still made up.........................................................................................................193What goes on behind God's feet, why Kiko picks up the cigarette, where Hollywood is, and how Mickey Mouse learns to answer.................................................................................................199I've made lists............................................................................................................................................................................................................218Comrade-in-chief of all that's unfinished..................................................................................................................................................................................256

Chapter One

How long a heart attack takes over a hundred metres, how heavy a spider's life weighs, why a sad man writes to the cruel river, and what magic the comrade-in-chief of the unfinished can work

Grandpa Slavko measured my head with Granny's washing line, I got a magic hat, a pointy magic hat made of cardboard, and Grandpa Slavko said: I'm really still too young for this sort of thing, and you're already too old.

So I got a magic hat with yellow and blue shooting stars on it, trailing yellow and blue tails, and I cut out a little crescent moon to go with them and two triangular rockets. Gagarin was flying one, Grandpa Slavko was flying the other.

Grandpa, I can't go out in this hat!

I should just hope not!

On the morning of the day when he was to die in the evening, Grandpa Slavko made me a magic wand from a stick and said: there's magic in that hat and wand. If you wear the hat and wave the wand you'll be the most powerful magician in the non-aligned states. You'll be able to revolutionise all sorts of things, just so long as they're in line with Tito's ideas and the statutes of the Communist League of Yugoslavia.

I doubted the magic, but I never doubted my grandpa. The most valuable gift of all is invention, imagination is your greatest wealth. Remember that, Aleksandar, said Grandpa very gravely as he put the hat on my head, you remember that and imagine the world better than it is. He handed me the magic wand, and I doubted nothing any more.

It's usual for people to think sadly of the dead now and then. In our family that happens when Sunday, rain, coffee and Granny Katarina all come together at the same time. Granny sips from her favourite cup, the white one with the cracked handle, she cries and remembers all the dead and the good things they did before dying got in the way. Our family and friends are at Granny's today because we're remembering Grandpa Slavko who's been dead for two days, dead for now anyway, just until I can find my magic wand and my hat again.

Still not dead in my family are Mother, Father, and Father's brothers-Uncle Bora and Uncle Miki. Nena Fatima, my mother's mother, is well in herself, it's only her ears and her tongue that have died-she's deaf as a post and silent as a snowfall, as they say. Auntie Gordana isn't dead yet either, she's Uncle Bora's wife and pregnant. Auntie Gordana, a blonde island in the dark sea of our family's hair, is always called Typhoon because she's four times livelier than normal people, she runs eight times faster and talks at fourteen times the usual speed. She even sprints from the loo to the wash basin, and at the cash desk in shops she's worked out the price of everything before the cashier can tap it in.

They've all come to Granny's because of Grandpa Slavko's death, but they're talking about the life in Auntie Typhoon's belly. Everyone is sure she'll have her baby on Sunday at the latest, or at the very, very latest on Monday, months early but already as perfect as if it were in the ninth month. I suggest calling the baby Speedy Gonzales. Auntie Typhoon shakes her blonde curls, says all in a rush: are-we-Mexicans-or-what? It'll-be-a-girl- not-a-mouse! She's-going-to-be-called-Ema.

Or Slavko, adds Uncle Bora quietly, Slavko if it's a boy.

There's a lot of love around for Grandpa Slavko today among all the people in black drinking coffee with Granny Katarina, and taking surreptitious looks at the sofa where Grandpa was sitting when Carl Lewis set the new world record in Tokyo. Grandpa died in 9.86 seconds flat, his heart was racing right up there with Carl Lewis, they were neck and neck. Then his heart stopped and Carl ran on like crazy. Grandpa gasped, and Carl flung his arms up in the air and threw an American flag over his shoulders.

The mourners bring chocolates and sugar cubes, cognac and schnapps. They want to console Granny with sweet things in her grief, they want to comfort themselves for their own grief with drink. Male mourning smells of after-shave. It stands in small groups in the kitchen, getting sozzled. Female mourning sits around the living-room table with Granny suggesting names for the new life in Auntie Typhoon's belly and discussing the right way to put a baby down to sleep in its first few months. When anyone mentions Grandpa's name the women cut up cake and hand slices round. They add sugar to their coffee and stir it with spoons that look like toys.

Women always praise the virtues of cake.

Great-Granny Mileva and Great-Grandpa Nikola aren't here because their son is going home to them in Veletovo, to be buried in the village where he was born. What the two have to do with each other I don't know. You should be allowed to be dead where you really liked being when you were alive. My father down in our cellar, for instance, which he calls his studio and he hardly ever leaves it, among his canvases and brushes. Granny anywhere just so long as her women neighbours are there too and there's coffee and chocolates. Great-Granny and Great-Grandpa under the plum trees in their orchard in Veletovo. Where has my mother really liked being?

Grandpa Slavko in his best stories, or underneath the Party office.

I may be able to manage without him for another two days. My magic things are sure to turn up by then.

I'm looking forward to seeing Great-Grandpa and Great-Granny again. Ever since I can remember they haven't smelled very sweet, and their average age is about a hundred and fifty. All the same, they're the least dead and the most alive of the whole family if you leave out Auntie Typhoon, who doesn't count, she's more of a natural catastrophe than a human being and she has a propeller in her backside. So Uncle Bora sometimes says, kissing his natural catastrophe's back.

Uncle Bora weighs as many kilos as my great-grandparents are old.

Someone else in my family who's not dead yet is Granny Katarina, although on the evening when Grandpa's great heart died of the fastest illness in the world she wished she was and wailed: all alone, what's to become of me without you, I don't want to be all alone, Slavko, oh, my Slavko, I'm so sad!

I was less afraid of Grandpa's death than of Granny's great grief crawling about on its knees like that: all alone, how am I going to live all alone? Granny beat her breast at Grandpa's dead feet and begged to be dead herself. I was breathing fast, but not easily. Granny was so weak that I imagined her body going all soft on the floor, soft and round. On TV a large woman jumped into the sand and looked happy about it. At Grandpa's feet, Granny shouted to the neighbours to come round, they unbuttoned his shirt, Grandpa's glasses slipped, his mouth was twisted to one side-I cut things out in my mind, the way I always do when I'm at a loss, more stars for my magic hat. In spite of being afraid, and though it was so soon after a death, I noticed that Granny's china dog on the TV set had fallen over and the plate with fishbones left from supper was still standing on the crochet tablecloth. I could hear every word the neighbours said as they bustled about, I heard it all in spite of Granny's whimpering and howling. She tugged at Grandpa's legs, Grandpa slid forward off the sofa. I hid in the corner behind the TV. But not a thousand TV sets could have hidden Granny's distorted face from me, or Grandpa falling off the sofa twisted all sideways, or the thought that I'd never seen my grandparents look uglier.

I'd have liked to put my hand on Granny's shaking back-her blouse would have been wet with sweat-and I'd have liked to say: Granny, don't! It will be all right. After all, Grandpa's a Party member, and the Party agrees with the Statutes of the Communist League, it's just that I can't find my magic wand at the moment. It's going to be all right again, Granny.

But her grief-stricken madness silenced me. The louder she cried, flailing around: leave me alone! the less courageous I felt in my hiding-place. The more the neighbours turned away from Grandpa and went to Granny instead, trying to console someone obviously inconsolable, as if they were selling her something she didn't need in the least, the more frantically she defended herself. As more and more tears covered her cheeks, her mouth, her lamentation, her chin, like oil coating a pan, I cut out more and more little details of the living-room: the bookcase with works by Marks, Lenin and Kardelj, Das Kapital at the left on the bottom shelf, the smell of fish, the branches of the pattern on the wallpaper, four tapestry pictures on the wall-children playing in a village street, brightly coloured flowers in a brightly coloured vase, a ship on a rough sea, a little cottage in the forest-a photograph of Tito and Gandhi shaking hands, right above and between the ship and the cottage, someone saying: how do we get her off him?

More and more people came along, one taking another's place as if to catch up with something, or at least not miss out on anything else, anxious to be as lively as possible in the presence of death. Grandpa's death had been too quick. It upset the neighbours, it made them look guiltily at the floor. No one had been able to keep up with Grandpa's heart running its race, not even Granny: oh no, why, why, why, Slavko? Teta Amela from the second floor collapsed. Someone cried: oh, sacred heart of Jesus! Someone else immediately cursed the mother of Jesus and several other members of his family. Granny tugged at Grandpa's trouser legs, hit out at the two paramedics who appeared in the living-room with their little bags. Keep your hands off him, she cried. Under their white coats the paramedics wore lumberjacks' shirts, and they hauled Granny off Grandpa's legs as if prising a sea-shell off a rock. As Granny saw it, Grandpa wouldn't be dead until she let go of him. She wasn't letting go. The men in white coats listened to Grandpa's chest. One of them held a mirror to his face and said: no, nothing.

I shouted that Grandpa was still there, his death didn't conform to the aims and ideals of the Communist League. You just get out of the way, give me my magic wand and I'll prove it!

No one took any notice of me. The lumberjack-paramedics put their hands inside Grandpa's shirt and shone a pencil flashlight in his eyes. I pulled out the electric cable, and the TV shut off. There were loose cobwebs hanging in the corner next to the power point. How much lighter does a spider's death weigh than a human death? Which of her husband's dead legs does the spider's wife cling to? I decided that I would never put a spider in a bottle and run water slowly into it again.

Where was my magic wand?

I don't know how long I stood in the corner before my father grabbed my arm as if taking me prisoner. He handed me over to my mother, who hauled me down the stairs and out into the yard. The air smelled of mirabelles mashed to make schnapps, there were fires burning in the megdan. You can see almost the whole town from the megdan, perhaps you can even see into the yard in front of the big five-storey block, practically a high-rise building for Visegrad, where a young woman with long black hair and brown eyes was bending down to a boy with hair the same colour and the same almond-shaped eyes. She blew some strands of hair off his forehead, her eyes filled with tears. No one on the megdan could hear what she was whispering to the boy. And perhaps no one could see that after the woman had taken the boy in her arms and hugged him for a long, long time, he nodded. The way you nod when you're promising something.

On the evening of the third day after Grandpa Slavko's death I'm sitting in the kitchen, looking through photograph albums. I take all the photos of Grandpa Slavko out of the album. I still don't know what I'm going to do with them. Out in the yard our cherry tree is arguing with the wind, it's stormy. When I've fixed it so that Grandpa Slavko can come alive again, for my next trick I'll make us all able to keep hold of noises. Then we can put the wind in the cherry-tree leaves into an album of sounds, along with the rumble of thunder and dogs barking by night in summer. And this is me chopping wood for the stove-that's how we'll be proudly presenting our life in sounds, the way we show holiday snaps of the Adriatic. We'll be able to carry small sounds about by hand. I'd cover up the anxiety on my mother's face with the laughter she laughs on her good days.

The brownish photos with broad white rims smell of plastic tablecloths, and show people with funny trousers getting wider at the bottom. There's a short man in a railwayman's uniform standing in front of the faades of an unfinished Visegrad, looking straight ahead, upright as a soldier: Grandpa Rafik.

Grandpa Rafik, my mother's father, died for good a long time ago, he drowned in the river Drina. I hardly knew him, but I can remember one game we played, a simple game. Grandpa Rafik would point to something and I'd say its name, its colour, and the first thing that occurred me about it. He pointed to his penknife, and I said: knife, grey, and railway engine. He pointed to a sparrow, and I said: bird, grey, and railway engine. Grandpa Rafik pointed through the window out at the night, and I said: dreams, grey, and railway engine, and Grandpa tucked me up and said: sleep an iron sleep.

The time of my grey period was the time of my visits to the eye specialist, who diagnosed nothing except that I could see things too fast, for instance the sequence of little letters and big letters on his wall chart. You'll have to cure him of that somehow, Mrs Krsmanovic, said the eye specialist, and he prescribed drops for her own eyes, which were always reddened.

I was very scared of trains and railway engines at that time. Grandpa Rafik had taken me to the disused railway tracks, he scratched flaking paint off the old engine, you've broken my heart, he whispered, rubbing the black paint between the palms of his hands. On the way home-paving-stone, grey, railway engine, my hand in his large one, black with sharp scraps of peeling paint-I decided to be nice to railway trains, because now he had me worried about my heart. But it was a long time since any trains had passed through our town. A few years later the first girl I loved, Danijela with her very long hair who didn't return my love, showed me how silly I'd been to protect my heart from being broken by trains, because she was the one who would show me the true meaning of a broken heart.

Peeling scraps of paint and the grey game are all I remember of Grandpa Rafik, unless old photos count as memories. And Grandpa Rafik is absent from our home in general. However often and however readily my family like to talk about themselves and other families and the dead, over coffee among themselves and with those other families, Grandpa Rafik is very seldom mentioned. No one ever looks at the coffee grounds in a cup and sighs: oh, Rafik, my Rafik, if only you were here! No one ever wonders what Grandpa Rafik would say about something, his name isn't spoken with either gratitude or disapproval.

No dead person can be less alive than Grandpa Rafik.

The dead are lonely enough in the earth where they lie, so why do we leave even the memory of Grandpa Rafik to be lonely?

Mother comes into the kitchen and opens the fridge. She's going to make sandwiches to take to work, she puts butter and cheese on the table. I look at her face, searching it for Grandpa Rafik's face in the photos.

Mama, do you look like Grandpa Rafik? I ask when she sits dwn at the table and unwraps the bread. She cuts up tomatoes. I wait and ask the question again, and only now does Mother stop, knife-blade on a tomato. What kind of grandpa was Grandpa Rafik? I ask again, why does no one talk about him? How am I ever going to know what kind of a grandpa I had?

Mother puts the knife aside and lays her hands in her lap. Mother raises her eyes. Mother looks at me.

You didn't have a real grandpa, Aleksandar, only a sad man. He mourned for his river and his earth. He would kneel down, scratch about in that earth of his until his fingernails broke and the blood came. He stroked the grass and smelled it and wept into the tufts of grass like a tiny child-my dear earth, you're trodden underfoot, at the mercy of any kind of weight. You didn't have a real grandpa, only a stupid man. He drank and drank. He ate earth, he brought earth up, then he crawled to the bank on all fours and washed his mouth out with water from the river. How that sad man loved his river! And his cognac-a stupid man who could love only what he saw as humbled and subjugated. Who could love only if he drank and drank.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from How the Soilder Repairs the Gramophoneby Sasa Stanisic Copyright © 2006 by Luchterhand Literaturverlag, Munch. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

£ 2.80 shipping within United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsBuy New

View this item£ 26.21 shipping from U.S.A. to United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, United Kingdom

Hardback. Condition: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR013643109

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, United Kingdom

Hardback. Condition: Good. The book has been read but remains in clean condition. All pages are intact and the cover is intact. Some minor wear to the spine. Seller Inventory # GOR014376795

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. First Edition, 1st printing in English. Ship within 24hrs. Satisfaction 100% guaranteed. APO/FPO addresses supported. Seller Inventory # 0802118666-8-1

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1ST. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 5967480-6

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1ST. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP68182619

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.22. Seller Inventory # G0802118666I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: Glands of Destiny First Edition Books, Sedro Woolley, WA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Like New. Publisher: Grove Press, New York, 2008.First Edition, First Printing. FINE hardcover book in FINE dust-jacket. Pristine. As new. Unread. All of our books with dust-jackets are shipped in fresh, archival-safe mylar protective sleeves. Seller Inventory # 2006300003

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: Abacus Bookshop, Pittsford, NY, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Fine copy in fine dust jacket. 1st. 8vo, 345 pp., Translated from the German by Anthea Bell. Seller Inventory # 102602

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone

Seller: 2Vbooks, Derwood, MD, U.S.A.

Hard cover. Condition: Fine in fine dust jacket. Sewn binding. Cloth over boards. 345 p. Audience: General/trade. No previous owner's name. Clean, tight pages. No bent corners. No remainder marks. HC 353. Seller Inventory # Alibris.0046974

Quantity: 1 available

How the Soldier Repairs the Gr

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00088609481

Quantity: 2 available