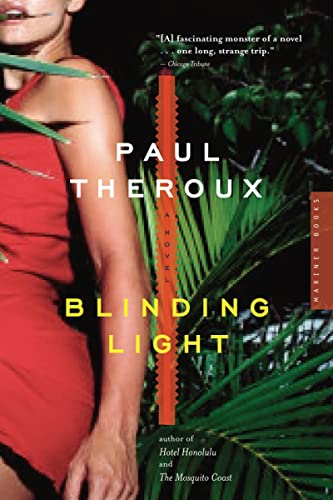

Items related to Blinding Light: A Novel

Synopsis

From the New York Times best-selling author Paul Theroux, Blinding Light is a slyly satirical novel of manners and mind expansion. Slade Steadman, a writer who has lost his chops, sets out for the Ecuadorian jungle with his ex-girlfriend in search of inspiration and a rare hallucinogen. The drug, once found, heightens both his powers of perception and his libido, but it also leaves him with an unfortunate side effect: periodic blindness. Unable to resist the insights that enable him to write again, Steadman spends the next year of his life in thrall to his psychedelic muse and his erotic fantasies, with consequences that are both ecstatic and disastrous.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Paul Theroux is the author of many highly acclaimed books. His novels include Burma Sahib, The Bad Angel Brothers, The Lower River, Jungle Lovers, and The Mosquito Coast, and his renowned travel books include Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, On the Plain of Snakes, and Dark Star Safari. He lives in Hawaii and on Cape Cod.

From the Back Cover

From the jungles of Ecuador to the island of Martha's Vineyard, Paul Theroux's new novel titillates with eroticism, intelligence, and wit.

Slade Steadman is the ultimate one-book wonder. His lone opus, published twenty years ago, was a cult classic about his travels through dozens of countries without benefit of passport. With his soon-to-be-ex-girlfriend in tow, he sets out for Ecuador's easternmost jungle in search of a rare hallucinogenic drug and what he hopes will be the cure for his writer's block.

But his world is altered profoundly when he becomes addicted to the drug and the insights it provides, only to have them desert him, along with his sight. Will he regain his vision? His visions? Or will he forgo the world of his imagining and his ambition? As Theroux leads us toward the answers, he makes fresh magic out of the venerable, intertwined themes of sight and insight. He also offers incisive, sometimes hilarious takes on the manifold ironies of travel and the trappings of the writer's life -- from the fear of the blank page to the unexpected challenges of the book tour.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Blinding Light

By Paul TherouxMariner Books

Copyright © 2006 Paul TherouxAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780618711963

Wishing to go where you don't belong is the condition of most people in the

world" was the opening sentence of Trespassing. The man with that sentence

in his head had turned and lifted his sleep mask to glance back at the

passengers who were masked and sleeping in their seats on the glary one-

class night flight.

The blindfolded people were strapped down, slumped sideways on

their safety straps, with tilted faces and gaping mouths, enclosed by the howl

of monologuing jet engines. The man excited his imagination by seeing them

as helpless captives or hostages, yet he knew better. Like him, they were

tired travelers going south — maybe some of them on the same drug tour,

but he hoped not. This man slipping back into his seat and readjusting his

mask was Slade Steadman, the author of Trespassing.

"Travel book" was the usual inadequate way of describing this

work, his only published book, but one that had made him famous, and later,

for unexpected reasons, very wealthy. He was so famous he would hide

himself, so wealthy he would never have to write another word for money.

This account of one of the riskiest and most imaginative journeys of the

modern era was an obvious stunt remembered as an epic.

The idea could not have been simpler, but his seeing it through to

a successful conclusion was another matter; that he had survived to tell the

whole story was his achievement. Steadman had traveled through Europe,

Asia, and Africa, twenty-eight countries and fifty-odd border crossings,

defying authority, for all of it — arrests, escapes, illegal entries, dangerous

flights, near disasters, river fordings, sneaking over frontiers — had been

accomplished without a passport. No papers, no visas, no credit cards, no ID

at all. Covert Insertions — the military term for his mission — had been a

working title, but squirming at its ambiguity, the publisher had discouraged

Steadman from using it.

Not only had he been undocumented during his entire yearlong

trip, alone, an alien, struggling against officialdom to keep alive and moving;

he had not carried a bag. "If it doesn't fit into my pocket I don't need it," he

had written, and it was now as well known a line as the one about wishing to

go where you don't belong. Around the World Without a Passport was the

subtitle of the book: the plight of a fugitive. It was the way he felt right now,

twenty years later, restless in his aisle seat on the flight to Quito with the

blindfolded passengers who were trying to sleep. For all of those twenty

years he had tried to write a second book.

He had not been surprised to see the young woman snoring in the

seat behind him with a recent edition of his book on her lap. Readers of

Trespassing — and over the years there had been millions — often took trips

like this, involving distance and a hint of risk. The book had inspired

imitations — the journey as a stunt — though no other writer had matched

him in his travel. Even Steadman himself, who now saw Trespassing as

something of a fluke, had failed to follow it up with an equally good book — or

any book — in the decades since publication. And that was another reason

he was on this plane.

They were two hours into the flight, after a long unscheduled

layover in Miami, but the delay had been eased for Steadman by his spotting

the woman at his gate reading a copy of Trespassing. It was the edition with

the TV series tie-in cover showing the handsome actor who played the twenty-

nine-year-old illegal border-crosser. And of course the actor wore a leather

jacket. At the time of publication much was made of the fact that Steadman

had traveled without luggage, wearing only a leather jacket. He had not

realized how this simple expedient of not carrying a bag had made him more

of a hero. The bruised and scuffed jacket with its many pockets was part of

his identity, but when it became a standard prop in the television show,

Steadman stopped wearing a leather jacket.

Watching the woman read his book with rapt attention — she did

not see him or even glance up — and liking her trance-like way of turning the

pages, helped pass the time for Steadman. He felt self-conscious at the sight

of this old success, but gratified that so many people still read the book,

even the ones who were following the reruns of the TV series. He had

wondered if the woman reading it would be among the passengers on this

Ecuador flight, looking helpless and passive. And of course she was.

In the seat next to Steadman, his girlfriend, Ava Katsina, stirred in

her sleep. Seeing her, too, blindfolded like a hostage, he felt a throb of lust.

The blood whipping through his gut and his fingers and his eyes made him

jittery with desire.

That was welcome. The sexual desire he had once described in

starved paragraphs of solitude in Trespassing as akin to cannibal hunger was

something he had not tasted for a long time. Ava, a medical doctor, had

said, "Are you past it? Do you want me to write you a prescription?"

At fifty Steadman was sure he was not past it, but his years of

struggling to attempt another book had afflicted him and visited impotence on

him too many times for him to believe it was a coincidence. Virility, he

thought, was not just an important trait in an imaginative person but was a

powerful determiner of creativity. Women writers were no different: the best of

them could be lavish lovers, as ramping and reckless as men — at least the

ones he had known when he had been the same. But those days were gone.

This slackness was another reason he and Ava had decided to

split up, and the decision had been made months ago. The trip they had

planned as a couple could not be canceled, and so, rather than lose their

deposit and forgo the tour, they were traveling together. What looked like

commitment, the quiet couple sharing the elbow rest, sitting side by side on

this long flight, was their following through on the promise, a favor more than

a duty, with no expectation of pleasure. When the trip was over, their

relationship was over. The trip itself was a gesture of finality — this flight was

part of their farewell, something civilized to share before they parted. And

here he was, wanting to eat her.

For years Steadman had felt well enough established as a writer

to shun rather than seek publicity. Now, he did not in the least resemble the

author of Trespassing. That reckless soul was falsely fixed in people's minds

as only a one-book author can be, a brooding one-dimensional pinup in a

leather jacket. This man was his book, the narrator of that amazing journey.

The book was all that was known. The mentions of him in the press — fewer

as time passed, dwindling to a handful in recent years — described someone

he no longer recognized.

Trespassing was still selling, its title a byword for adventure. He

had paid his debts with his first profits and then began living well on the

paperback rights. The big house up-island on Martha's Vineyard he had

bought with the movie money. The TV series that came later made him

wealthy beyond any of his earlier dreams of success. But the author who

went under his name was a public fiction, elaborated and improved upon by

the movie and the TV shows. The TV host and traveler was now pictured on

the book jacket, and that well-known actor was fixed in the public mind and

more recognizable than Steadman himself, but possessing the traits

Steadman had established in the book. He was elusive, a risk taker,

unapproachable, inventive, uncompromising, a free spirit, highly educated,

physically strong, something of a Boy Scout, demanding, enigmatic, sexual,

full of surprises.

The handsome actor who was identified with the TV dramatization

of Steadman's book often made statements about travel, risk, and heroism —

even about writing, with enormous confidence, even when Steadman could

do almost no writing himself. As a stand-in for the reclusive Steadman, the

actor was now and then employed as a motivational speaker, using the

challenges of his television experiences making the show — most of it was

filmed in Mexico — as his text. He did so portentously, in the tone of a

seasoned traveler, as though he were responsible for the book. And

Trespassing had spawned so many imitators it created a genre, inspiring a

sort of travel of which this Ecuador trip was typical: a leap in the dark. Before

Trespassing there had been travel of this kind but few persuasive books about

it. Steadman had made it an accessible narrative, popularized it, given it

drama. He had succeeded in making the world seem dangerous and difficult

again, full of unpredictable people and narrow escapes, a debauch of

experience, as in an earlier age of travel.

The merchandising that came later astonished him. Just the

notion of it seemed weird, especially since he had not published any other

book. A man he despised at the agency that had promoted it and sold it had

said to him: "Don't write anything else, or if you do, make it another

Trespassing. Don't you see what you've done? By not writing another book

you've made yourself into a brand."

After Steadman licensed the name, it was more than a name; it

was a logo, a lifestyle, a clothing line that was expressly technical, a range

of travel gear, of sunglasses and accessories — knives, pens, lighters. The

leather jacket had been the first piece of merchandise, and as a signature

item it was still selling. The luggage came later. The clothing changed from

year to year. The newest line was watches ("timepieces — 'watches' does

not describe them"), some of them very expensive: chronometers for divers,

certified for two hundred meters; a model with a built-in altimeter for pilots;

many for hikers; one in gold and titanium. The licensed brand was

Trespassing Overland Gear. The motto, a line from the book, was "Cross

borders — don't ask permission."

How popular was all this? He knew a great deal from the revenue,

which seemed to him vast and unspendable, but he often wondered what sort

of people bought the stuff, because he so seldom went out and he avoided

using any of it himself. Now he saw that the clothes on that woman behind

him with his book on her lap were from the catalogue; and the man next to

her, the others around her, all of them wore travel outfits bearing the TOG

logo of a small striding figure in a signature leather jacket.

Merchandising and relicensing the name produced such a large

and regular income that Steadman had long since stopped writing for money.

He wanted only to produce another book worthy of his first one, but fiction —

as brave an interior journey as Trespassing had been a global one. He had

started writing the book, and spoke of it as work in progress, but for years he

had regarded it privately as work in stoppage. What he published now, the

occasional magazine articles and opinion pieces, were merely to remind the

world that he was still alive, and this reminder was a way of promising

another book.

Steadman liked to think he was in the middle of his career. But he

knew that for an American writer there is no middle. You were a hot new

author and then you were either an old hand or else forgotten. He was

somewhere deep in the second half and wishing he were younger. Everything

he had gladly done in the early part of his career he now avoided: the

readings, the signings, the appearances, the visits to colleges and

bookstores, the posed photographs and interviews, the favors to editors, the

sideshows at book festivals — he refused them all and wanted the opposite,

silence, obscurity, and remoteness. His refusals created the impression of

snooty contempt; his brusque deflecting ironies were taken to be bad temper.

Simply saying no, he was seen as grumpy, uncooperative, a snob. He did

not want to convey to these strangers how desperate he was. Having all that

merchandising money somehow made it worse.

Rather than agreeing to interviews and public appearances to

correct the false impression that readers had of him, he withdrew even

further; and in seclusion, without the envious mockery of journalists and

profile writers, he began to suspect that he might have written better — that

he could do better. He was hardly thirty when he wrote Trespassing. The

book was full of hasty judgments, but why tidy it now? He was known as a

travel writer, but he felt sure that fiction writing was his gift. Because so much

of Trespassing had been fiction — embroidered incidents, improved-upon

dialogue, outright invention — he knew he had a great novel in him. There

was still time to finish the book that would prove this.

He had started writing it. Ava had praised it; they were lovers then,

sharing their lives. In the course of their breakup she told him frankly that she

hadn't liked what he had read to her after all. The novel in progress was a

reflection of him: selfish, suffocating, manipulative, pretentious, incomplete,

and sexless.

"Writing is your dolly. You just sit around playing with it."

This same woman, listening naked in their bed to him reading part

of a chapter, had once said, "It's genius, Slade."

"You're probably one of the few writers in America who can afford

to treat writing as your dolly."

He protested, ranting like a man in a cage. Instead of consoling

him, Ava said, "You are such a fucking diva." He was demoralized for the

moment. He told himself he would be better when she was completely out of

his life. He took work for magazines — his factual story-chasing journalism

had always been resourceful and vivid, even shocking. He said, "I write it with

my left hand." The novel was what mattered to him. Yet what editor ever

said, "Write us some fiction"? His struggle to continue his novel wrecked his

relationship with Ava.

"You're just selfish," they both said.

When their love was gone, replaced by indifference and boredom,

a new Ava was revealed — or, not a new Ava, but perhaps the essential

woman: ambitious, sarcastic, resilient, demanding, predatory, sensual, much

funnier and more resourceful than she had been as his lover. Her intelligence

made these traits into weapons.

The delay in Miami proved her toughness. In the lounge, seated in

the crossfire of intrusive questions and small talk, most of it from nearby

passengers, expressing their impatience by gabbling, Steadman kept himself

customarily stone-faced and silent, wearing the implacable mask he had

fashioned for himself over the years of his withdrawal.

"On a tour?" one of the men said.

He was a big man, as bulky as his own Trespassing duffel bag, in

his late thirties. His badly slouching posture made him seem slovenly and

arrogant, and his anger gave him an overbearing and elbowing confidence.

Steadman had noticed that he demanded more space than anyone else, an

extra seat here in the lounge for his briefcase, his arms on both armrests, his

bulgy duffel filling the overhead rack. Walking confidently on kicking feet

toward the plane, he filled the jetway, pulling his valise on wheels that

trapped people behind him, even his wife, who remained talking on a cell

phone until the plane took off, and was on it again, urgently, saying, "I'll send

you all the bumf with a packet of swatches."

Steadman took his time, and at last he said, "Are you?"

"For want of a better word," the man said, and looked up, hearing

his wife say, "Hack?"

A dark scruffy man, bug-eyed and with spiky hair, was arguing

with a clerk at the check-in desk, saying in an insistent German accent, "But

that is falsch. I am on the list — Manfred Steiger. I am American."

Steadman thought: You went away to be alone — or, in his and

Ava's case, on a deliberate self-assigned mission — and you discovered your

traveling companions to be the very people you were hoping to flee, the ones

you most disliked. In this case, young overequipped couples — rich,

handsome, heedless, privileged, undeserving, and profoundly lazy in a

special selfish way — from this generation of small-minded entrepreneurial

emperors. And most of them were dressed in his clothes.

"God, how I loathe these people," Ava whispered to Steadman.

For one thing, they boasted of hating books and hardly read

newspapers. Trespassing didn't count, because it wasn't new and was better

known from movies and TV — Steadman was aware that some of the most

obnoxious people seemed to love it for its lawlessness, its self-indulgent rule-

breaking, and its tone of boisterous intrusion. I've only read one real book in

my life — yours, such people wrote him. That alone was enough, but it was

also an indication that you couldn't tell them anything. They didn't listen,

they didn't have to — they ran the whole world now. You turned me into a

world traveler.

The thing was to shut them down as quickly as possible.

Steadman had learned that, in an interview, if you fell silent and

watched and waited instead of answering, people volunteered more detail. In

this instance another man, a bystander, offered the detail.

"It's quote-unquote adventure travel," that man said.

"Eco-porn," Ava said. "Eco-chic. Voyeurism must be such a wet

dream for you."

That man winced, but the man named Hack said, "We're traveling

together. Didn't you see our T-shirts?"

He unbuttoned his khaki safari shirt, revealing the lettering on his

Tshirt: The Gang of Four.

"Until they finish the renovation on our house," the second man

was saying. "We're reconfiguring the interior of a lovely old Victorian.

We've got twelve thousand square feet. It's on an acre in a lovely

part of San Francisco. Sea Cliff? Robin Williams lives nearby, and so do

Hack and Janey."

"Marshall Hackler — call me Hack," said the big slouching man,

inviting a handshake with his carelessly thrust out arm.

And Janey was apparently the woman on the cell phone. She just

flapped her fingers and turned away, but another woman who had been

listening — she was pretty, bright-eyed, the one holding the paperback of

Trespassing, in a bush vest and green trousers, dressed for a safari —

smiled and said, "Ecuador. A year ago it was Rwanda. We were the last

people in there before the Africans massacred the people on that tour. We

had the same guide. He was almost killed. No one can go now. We were

incredibly lucky."

The woman speaking on the cell phone broke off and said, "We're

whole-hoggers. We want it all."

"Janey's doing the interior. But we're reconfiguring the outside,

too. Swales. Berms. I've got the footprint and the plans with me — still

working out siting of the lap pool. Downstream we'll be putting in a

guesthouse and sort of meld it with the landscaping."

Hack put his arm around the man and said, "This guy actually

wrote a book."

Dismissing this with a boastful smile, the man said, "For my

sins," then took a breath and added, "Anyway, I sold my company and got

into hedge funds. This was — oh, gosh — before the NASDAQ tanked in—

what? Last April?"

Steadman leaned toward him, saying nothing, smiling his obscure

smile at the self-conscious "oh, gosh."

"And I got in the high eight figures."

Hack said, "So he said to me, 'Let's get jiggy wid it.' 'Cause he's

an A-player. He's a well-known author, too."

At the mention of "high eight figures" — what was that, tens of

millions, right? — Ava barked loudly, as though at an outrage, and the

woman in the Trespassing vest glanced over her cell phone and said, "Do

keep it down. I'm talking."

"Wood worked for two solid years for that payday," the other

woman said, looking up from Steadman's book.

His name was Wood?

Janey, Hack's wife, was saying in a wiffling English accent into

her cell phone, "It seems frightful. But in point of fact, single people spend a

disproportionate amount of time in the loo. The laboratory, as you might say."

Both couples were dressed alike, mostly in Trespassing clothes

from the catalogue: trousers with zip-off legs that turned them into shorts,

shirts with zip-off sleeves, reversible jackets, thick socks, hiking shoes,

floppy hats, mesh-lined vests, and fanny packs at their waists.

Seeing them, Steadman wanted to say: I give away ten percent of

my pretax profits from catalogue sales to environmental causes. How much

do you contribute?

"This has something like seventeen pockets," the woman with the

book said, patting her vest, seeing that Ava was staring at it — but Ava was

staring at the TOG logo. She slapped it some more. "These gussets are

really useful. And check out this placket."

And when Ava's gaze drifted to the woman's expensive watch — it

was the Trespassing Mermaid — she said, "It's a chronometer. Titanium.

Certified for like a billion meters. That's your vacuum-release valve," and

twisted it. "We dive — Janey doesn't but she snorkels." The woman on the

phone turned away at the mention of her name and kept chewing on the

phone. "We're hoping to do some in the Galįpagos."

Steadman was so delighted to hear that they were going in the

opposite direction he did not tell them that snorkeling there was strictly

regulated, but encouraged her instead. The man he took to be her husband

was going through the sectioned-off pockets of his own padded vest. He

brought out a folded map and his boarding pass and a wallet that looked like

a small parcel, with slots for air tickets, dollar bills, and pesos. The wallet,

too, was a Trespassing accessory.

"What I love about American money is its tensile strength. It's the

high rag content. Leave a couple of bucks in a bathing suit and never mind.

All you have to do is dry it out. It actually stands up to a washer-dryer."

"You mean you can launder it?" Ava said.

Janey, the young woman with the English accent, said "Ta very

mooch for now" and "By-yee" and snapped her phone off, and collapsing it,

she turned it into a small dark cookie. The other woman reached into another

expensive catalogue item, the Trespassing Gourmet Lunch Tote, a padded

food satchel with a cooler compartment. She handed her husband a wrapped

sandwich.

"We always bring our own," Hack said, chewing between

bites. "It's smoked turkey with provolone and tomato and an herbed

vinaigrette dressing."

Noting that the man said "herbed," Ava frowned and turned away,

and the woman looked up from her book and offered Ava half a sandwich,

saying that she had plenty. Ava's tight smile meant "no thanks."

Tapping the cover of Trespassing, Hack put his arm around the

woman and said, "That must be one hell of a read."

The woman said, "It's awesome."

"Like how?"

"Like in its, um, modalities. In its, um, tropes."

"You've been reading it for weeks and ignoring me."

"I read real slow when I'm liking something."

"So who wrote it?"

Steadman, who had been listening closely, braced himself,

putting on his most implacable face.

The woman said, "This, like, you know, legendary has-been. The

outdoor- gear freak. He's more a lifestyle than a writer." Then, "You guys

married?"

Hearing "legendary has-been," Ava shut her eyes and smiled in

anger.

As for the question, everything about it, too, was wrong.

The "you," the "guys," the very word "married."

"I'm Sabra Wilmutt," the woman said.

"I'm Jonquil J. Christ."

Sabra's face looked suddenly slapped and lopsided. She said, "I

don't get it."

"The J is for Jesus."

As Ava spoke, the reboarding announcement was made.

What does it matter? Ava's expression said to Steadman, who

had heard it all. But Steadman had been attentive to the woman named

Sabra, immersed in Trespassing. It was just this awful flight to get through,

and after that they would never see any of them again.

Copyright © 2005 by Paul Theroux. Reprinted by permission of Houghton

Mifflin Company.

Continues...

Excerpted from Blinding Lightby Paul Theroux Copyright © 2006 by Paul Theroux. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Blinding Light: A Novel

Blinding Light: A Novel

Seller: Reliant Bookstore, El Dorado, KS, U.S.A.

Condition: good. This book is in good condition with very minimal damage. Pages may have minimal notes or highlighting. Cover image on the book may vary from photo. Ships out quickly in a secure plastic mailer. Seller Inventory # RDV.0618711961.G

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light: A Novel

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00079065821

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light: A Novel

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00071102105

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Reprint. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # GRP76408458

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Reprint. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 41913705-6

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.02. Seller Inventory # G0618711961I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.02. Seller Inventory # G0618711961I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.02. Seller Inventory # G0618711961I2N00

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.02. Seller Inventory # G0618711961I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Blinding Light: A Novel

Seller: HPB-Movies, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_430277227

Quantity: 1 available