Items related to South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking...

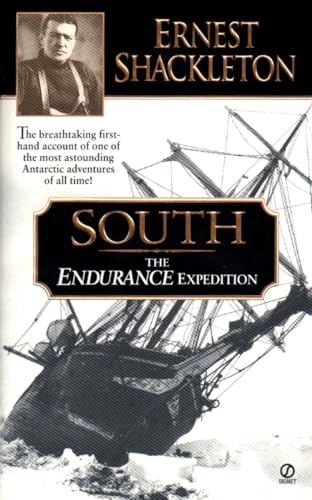

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of All Time - Softcover

Synopsis

In 1914, a party led by veteran explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton sets out to become the first to traverse the continent of Antarctica. Their initial optimism is short-lived, however, as the ice field slowly thickens, encasing the ship Endurance in a death-grip, crushing their craft, and marooning 28 men on a polar ice floe....

In an epic struggle of man versus the elements, Shackleton leads his team on a harrowing quest for survival over some of the most unforgiving terrain in the world. Icy, tempestuous seas full of gargantuan waves, mountainous glaciers and icebergs, unending brutal cold, and ever-looming starvation are their mortal foes as Shackleton and his men struggle to stay alive. What happened to those brave men forever stands as a testament to their strength of will and the power of human endurance. This is their story, as told by the man who led them."synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Sir Ernest Shackleton, C.V.O. (1874-1922) is regarded as perhaps the greatest of all Antarctic explorers. He was a member of Captain Scott's 1901-1903 expedition to the South Pole, and in 1907 led his own expedition on the whaler Nimrod, coming within ninety-seven miles of the South Pole, the feat for which he was knighted. The events of that expedition are chronicled in his first book, The Heart of the Antarctic. He is considered one of England's greatest heroes for his actions during the ill-fated Endurance expedition, leading all of his men to safety after being marooned for two years on the polar ice. South is his recounting of this expedition. He died at age forty-seven during his final expedition, and was buried in the whaler's cemetary on South Georgia Island in the South Atlantic.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

South

The Endurance ExpeditionBy Ernest Henry ShackletonSignet Book

Copyright © 1999 Ernest Henry ShackletonAll right reserved.

ISBN: 0451198808

Chapter One

CROSSING THE SOUTH POLE

INTO THE WEDDELL SEA

I had decided to leave South Georgia about December 5, and inthe intervals of final preparation scanned again the plans for thevoyage to winter quarters. What welcome was the Weddell Seapreparing for us? The whaling captains at South Georgia weregenerously ready to share with me their knowledge of the watersin which they pursued their trade, and, while confirming earlierinformation as to the extreme severity of the ice conditions in thissector of the Antarctic, they were able to give advice that was worthattention.

It will be convenient to state here briefly some of the considerationsthat weighed with me at that time and in the weeks thatfollowed. I knew that the ice had come far north that season,and, after listening to the suggestions of the whaling captains, haddecided to steer to the South Sandwich Group, round UltimaThule, and work as far to the eastward as the fifteenth meridianwest longitude before pushing south. The whalers emphasizedthe difficulty of getting through the ice in the neighbourhood ofthe South Sandwich Group. They told me they had often seenthe floes come right up to the Group in the summer-time, and theythought the Expedition would have to push through heavy pack inorder to reach the Weddell Sea. Probably the best time to getinto the Weddell Sea would be the end of February or the beginningof March. The whalers had gone right round the SouthSandwich Group and they were familiar with the conditions.The predictions they made had induced me to take the deck-load ofcoal, for if we had to fight our way through to Coats' Land wewould need every ton of fuel the ship could carry.

I hoped that by first moving to the east as far as the fifteenthmeridian west we would be able to go south through looser ice,pick up Coats' Land and finally reach Vahsel Bay, where Filchnermade his attempt at landing in 1912. Two considerations wereoccupying my mind at this juncture. I was anxious for certainreasons to winter the Endurance in the Weddell Sea, but thedifficulty of finding a safe harbour might be very great. If no safeharbour could be found, the ship must winter at South Georgia.It seemed to me hopeless now to think of making the journey acrossthe continent in the first summer, as the season was far advancedand the ice conditions were likely to prove unfavourable. Inview of the possibility of wintering the ship in the ice, we tookextra clothing from the stores at the various stations in SouthGeorgia.

The other question that was giving me anxious thought was thesize of the shore party. If the ship had to go out during thewinter, or if she broke away from winter quarters, it would bepreferable to have only a small, carefully selected party of menashore after the hut had been built and the stores landed. Thesemen could proceed to lay out depots by man-haulage and makeshort journeys with the dogs, training them for the long earlymarch in the following spring. The majority of the scientificmen would live aboard the ship, where they could do their workunder good conditions. They would be able to make short journeys,if required, using the Endurance as a base. All these planswere based on an expectation that the finding of winter quarterswas likely to be difficult. If a really safe base could be establishedon the continent, I would adhere to the original programme ofsending one party to the south, one to the west round the head ofthe Weddell Sea towards Graham Land, and one to the east towardsEnderby Land.

We had worked out details of distances, courses, stores required,and so forth. Our sledging ration, the result of experience as wellas close study, was perfect. The dogs gave promise, after training,of being able to cover fifteen to twenty miles a day withloaded sledges. The trans-continental journey, at this rate, shouldbe completed in 120 days unless some unforeseen obstacle intervened.We longed keenly for the day when we could begin thismarch, the last great adventure in the history of South Polarexploration, but a knowledge of the obstacles that lay between usand our starting-point served as a curb on impatience. Everythingdepended upon the landing. If we could land at Filchner'sbase there was no reason why a band of experienced men shouldnot winter there in safety. But the Weddell Sea was notoriouslyinhospitable, and already we knew that its sternest face was turnedtowards us. All the conditions in the Weddell Sea are unfavourablefrom the navigator's point of view. The winds are comparativelylight, and consequently new ice can form even in the summer-time.The absence of strong winds has the additional effectof allowing the ice to accumulate in masses, undisturbed. Thengreat quantities of ice sweep along the coast from the east underthe influence of the prevailing current, and fill up the bight of theWeddell Sea as they move north in a great semicircle. Some ofthis ice doubtless describes almost a complete circle, and is held upeventually, in bad seasons, against the South Sandwich Islands.The strong currents, pressing the ice masses against the coasts,create heavier pressure than is found in any other part of theAntarctic. This pressure must be at least as severe as the pressureexperienced in the congested North Polar basin, and I aminclined to think that a comparison would be to the advantage ofthe Arctic. All these considerations naturally had a bearingupon our immediate problem, the penetration of the pack and thefinding of a safe harbour on the continental coast.

The day of departure arrived. I gave the order to heaveanchor at 8.45 a.m. on December 5, 1914, and the clanking of thewindlass broke for us the last link with civilization. The morningwas dull and overcast, with occasional gusts of snow andsleet, but hearts were light aboard the Endurance. The long daysof preparation were over and the adventure lay ahead.

We had hoped that some steamer from the north would bringnews of the war and perhaps letters from home before our departure.A ship did arrive on the evening of the 4th, but she carriedno letters, and nothing useful in the way of informationcould be gleaned from her. The captain and crew were all stoutlypro-German, and the "news" they had to give took the unsatisfyingform of accounts of British and French reverses. Wewould have been glad to have had the latest tidings from a friendliersource. A year and a half later we were to learn that theHarpoon, the steamer which tends the Grytviken station, had arrivedwith mall for us not more than two hours after the Endurancehad proceeded down the coast.

The bows of the Endurance were turned to the south, and thegood ship dipped to the south-westerly swell, Misty rain fellduring the forenoon, but the weather cleared later in the day, andwe had a good view of the coast of South Georgia as we movedunder steam and sail to the south-east. The course was laid tocarry us clear of the island and then south of South Thule, SandwichGroup. The wind freshened during the day, and all squaresail was set, with the foresail reefed in order to give the look-outa clear view ahead; for we did not wish to risk contact with a"growler," one of those treacherous fragments of ice that floatwith surface awash. The ship was very steady in the quarterlysea, but certainly did not look as neat and trim as she had donewhen leaving the shores of England four months earlier. We hadfilled up with coal at Grytviken, and this extra fuel was storedon deck, where it impeded movement considerably. The carpenterhad built a false deck, extending from the poop-deck to thechart-room. We had also taken aboard a ton of whale-meat forthe dogs. The big chunks of meat were hung up in the rigging,out of reach but not out of sight of the dogs, and as the Endurancerolled and pitched, they watched with wolfish eyes for a windfall.

I was greatly pleased with the dogs, which were tethered aboutthe ship in the most comfortable positions we could find for them.They were in excellent condition, and I felt that the expeditionhad the right tractive-power. They were big, sturdy animals,chosen for endurance and strength, and if they were as keen topull our sledges as they were now to fight one another all wouldbe well. The men in charge of the dogs were doing their workenthusiastically, and the eagerness they showed to study the naturesand habits of their charges gave promise of efficient handlingand good work later on.

During December 6 the Endurance made good progress on asouth-easterly course. The northerly breeze had freshened duringthe night and had brought up a high following sea. The weatherwas hazy, and we passed two bergs, several growlers, and numerouslumps of ice. Staff and crew were settling down to the routine.Bird life was plentiful, and we noticed Cape pigeons,whale-birds, terns, mollymauks, nellies, sooty, and wanderingalbatrosses in the neighbourhood of the ship. The course was laidfor the passage between Sanders Island and Candlemas Volcano.December 7 brought the first check. At six o'clock that morningthe sea, which had been green in colour all the previous day,changed suddenly to a deep indigo. The ship was behaving wellin a rough sea, and some members of the scientific staff were transferringto the bunkers the coal we had stowed on deck. SandersIsland and Candlemas were sighted early in the afternoon, andthe Endurance passed between them at 6 p.m. Worsley's observationsindicated that Sanders Island was, roughly, three mileseast and five miles north of the charted position. Large numbersof bergs, mostly tabular in form, lay to the west of the islands,and we noticed that many of them were yellow with diatoms.One berg had large patches of red-brown soil down its sides. Thepresence of so many bergs was ominous, and immediately afterpassing between the islands we encountered stream-ice. All sailwas taken in and we proceeded slowly under steam. Two hourslater, fifteen miles north-east of Sanders Island, the Endurancewas confronted by a belt of heavy pack-ice, half a mile broadand extending north and south. There was clear water beyond,but the heavy south-westerly swell made the pack impenetrablein our neighbourhood. This was disconcerting. The noon latitudehad been 57 [degrees] 26' S., and I had not expected to find pack-icenearly so far north, though the whalers had reported pack rightup to South Thule.

The situation became dangerous that night. We pushed intothe pack in the hope of reaching open water beyond, and foundourselves after dark in a pool which was growing smaller andsmaller. The ice was grinding around the ship in the heavyswell, and I watched with some anxiety for any indication of achange of wind to the east, since a breeze from that quarterwould have driven us towards the land. Worsley and I were ondeck all night, dodging the pack. At 3 a.m. we ran south, takingadvantage of some openings that had appeared, but met heavyrafted pack-ice, evidently old; some of it had been subjected tosevere pressure. Then we steamed north-west and saw openwater to the north-east. I put the Endurance's head for the opening,and, steaming at full speed, we got clear. Then we went eastin the hope of getting better ice, and five hours later, after somedodging, we rounded the pack and were able to set sail oncemore. This initial tussle with the pack had been exciting attimes. Pieces of ice and bergs of all sizes were heaving andjostling against each other in the heavy south-westerly swell. Inspite of all our care the Endurance struck large lumps stem on,but the engines were stopped in time and no harm was done.The scene and sounds throughout the day were very fine. Theswell was dashing against the sides of huge bergs and leapingright to the top of their icy cliffs. Sanders Island lay to thesouth, with a few rocky faces peering through the misty, swirlingclouds that swathed it most of the time, the booming of the searunning into ice caverns, the swishing break of the swell on theloose pack, and the graceful bowing and undulating of the innerpack to the steeply rolling swell, which here was robbed of itsbreak by the masses of ice to windward.

We skirted the northern edge of the pack in clear weather witha light south-westerly breeze and an overcast sky. The bergswere numerous. During the morning of December 9 an easterlybreeze brought hazy weather with snow, and at 4.30 p.m. we encounteredthe edge of pack-ice in Int. 58 [degrees] 27' S., long. 29 [degrees] 08' W.It was one-year-old ice interspersed with older pack, ail heavilysnow-covered and lying west-south-west to east-north-east. We enteredthe pack at 5 p.m., but could not make progress, and clearedit again at 7.40 p.m. Then we steered east-north-east and spentthe rest of the night rounding the pack. During the day we hadseen adelie and ringed penguins, also several humpback and finnerwhales. An ice-blink to the westward indicated the presence ofpack in that direction. After rounding the pack we steered S.40 [degrees] E., and at noon on the 10th had reached lat. 58 [degrees] 28' S.,long. 20 [degrees] 28' W. Observations showed the compass variation to be1 1/2 [degrees] less than the chart recorded. I kept the Endurance onthe course till midnight, when we entered loose open ice about ninetymiles south-east of our noon position. This ice proved to fringethe pack, and progress became slow. There was a long easterlyswell with a light northerly breeze, and the weather was clearand fine. Numerous bergs lay outside the pack.

The Endurance steamed through loose open ice till 8 a.m. onthe 11th, when we entered the pack in lat. 59 [degrees] 46' S., long.18 [degrees] 22' W. We could have gone further east, but the pack extendedfar in that direction, and an effort to circle it might have involveda lot of northing. I did not wish to lose the benefit of theoriginal southing. The extra miles would not have mattered to aship with larger coal capacity than the Endurance possessed, butwe could not afford to sacrifice miles unnecessarily. The packwas loose and did not present great difficulties at this stage. Theforesail was set in order to take advantage of the northerly breeze.The ship was in contact with the ice occasionally and receivedsome heavy blows. Once or twice she was brought up all standingagainst solid pieces, but no harm was done. The chief concernwas to protect the propeller and rudder. If a collision seemedto be inevitable the officer in charge would order "slow" or"half speed" with the engines, and put the helm over so as tostrike the floe a glancing blow. Then the helm would be put overtowards the ice with the object of throwing the propeller clearof it, and the ship would forge ahead again. Worsley, Wild,and I, with three officers, kept three watches while we were workingthrough the pack, so that we had two officers on deck all the time.The carpenter had rigged a six-foot wooden semaphore on thebridge to enable the navigating officer to give the seamen orscientists at the wheel the direction and the exact amount of helmrequired. This device saved time as well as the effort of shouting.We were pushing through this loose pack all day, and theview from the crow's-nest gave no promise of improved conditionsahead. A Weddell seal and a crab-eater seal were noticedon the floes, but we did not pause to secure fresh meat. It wasimportant that we should make progress towards our goal asrapidly as possible, and there was reason to fear that we shouldhave plenty of time to spare later on if the ice conditions continuedto increase in severity.

On the morning of December 12 we were working through loosepack which later became thick in places. The sky was overcastand light snow was falling. I had all square sail set at 7 a.m. inorder to take advantage of the northerly breeze, but it had to comein again five hours later when the wind hauled round to the west.The noon position was lat. 60 [degrees] 26' S., long. 17 [degrees] 58' W.,and the run for the twenty-four hours had been only 33 miles. The icewas still badly congested, and we were pushing through narrowleads and occasional openings with the floes often close abeam oneither side. Antarctic, snow, and stormy petrels, fulmars, white-rumpedterns, and adelies were around us. The quaint little penguinsfound the ship a cause of much apparent excitement andprovided a lot of amusement aboard. One of the standing jokeswas that all the adelies on the floe seemed to know Clark and,when he was at the wheel, rushed along as fast as their legs couldcarry them, yelling out "Clark! Clark!" and apparently veryindignant and perturbed that he never waited for them or evenanswered them.

We found several good leads to the south in the evening, andcontinued to work southward throughout the night and the followingday. The pack extended in all directions as far as the eyecould reach. The noon observation showed the run for thetwenty-four hours to be 54 miles, a satisfactory result under theconditions. Wild shot a young Ross seal on the floe, and wemanoeuvred the ship alongside. Hudson jumped down, bent aline on to the seal, and the pair of them were hauled up. Theseal was 4 ft. 9 in. long and weighed about ninety pounds. Hewas a young male and proved very good eating, but when dressedand minus the blubber made little more than a square meal forour twenty-eight men, with a few scraps for our breakfast and tea.The stomach contained only amphipods about an inch long, alliedto those found in the whales at Grytviken.

The conditions became harder on December 14. There wasa misty haze, and occasional falls of snow. A few bergs were insight. The pack was denser than it had been on the previousdays. Older ice was intermingled with the young ice, and ourprogress became slower. The propeller received several blowsin the early morning, but no damage was done. A platform wasrigged under the jibboom in order that Hurley might secure somekinematograph pictures of the ship breaking through the ice.The young ice did not present difficulties to the Endurance, whichwas able to smash a way through, but the lumps of older icewere more formidable obstacles, and conning the ship was a taskrequiring close attention. The most careful navigation could notprevent an occasional bump against ice too thick to be broken orpushed aside. The southerly breeze strengthened to a moderatesouth-westerly gale during the afternoon, and at 8 p.m. we hoveto, stem against a floe, it being impossible to proceed withoutserious risk of damage to rudder or propeller. I was interested tonotice that, although we had been steaming through the pack forthree days, the north-westerly swell still held with us. It addedto the difficulties of navigation in the lanes, since the ice wasconstantly in movement.

The Endurance remained against the floe for the next twenty-fourhours, when the gale moderated. The pack extended to thehorizon in all directions and was broken by innumerable narrowlanes. Many bergs were in sight, and they appeared to be travellingthrough the pack in a south-westerly direction under thecurrent influence. Probably the pack itself was moving northeastwith the gale. Clark put down a net in search of specimens,and at two fathoms it was carried south-west by the current andfouled the propeller. He lost the net, two leads, and a line.Ten bergs drove to the south through the pack during the twentyfour hours. The noon position was lat. 61 [degrees] 31' S., long.18 [degrees] 12' W. The gale had moderated at 8 p.m., and we made five milesto the south before midnight and then stopped at the end of a longlead, waiting till the weather cleared. It was during this shortrun that the captain, with semaphore hard-a-port, shouted to thescientist at the wheel: "Why in Paradise don't you port!"The answer came in indignant tones: "I am blowing my nose."

The Endurance made some progress on the following day.Long leads of open water ran towards the south-west, and the shipsmashed at full speed through occasional areas of young ice tillbrought up with a heavy thud against a section of older floe.Worsley was out on the jibboom end for a few minutes whileWild was conning the ship, and he came back with a glowingaccount of a novel sensation. The boom was swinging high andlow and from side to side, while the massive bows of the shipsmashed through the ice, splitting it across, piling it mass on massand then shouldering it aside. The air temperature was 37 [degrees]Fahr., pleasantly warm, and the water temperature 29 [degrees] Fahr.We continued to advance through fine long leads till 4 a.m. onDecember 17, when the ice became difficult again. Very largefloes of six-months-old ice lay close together. Some of these floespresented a square mile of unbroken surface, and among themwere patches of thin ice and several floes of heavy old ice. Manybergs were in sight, and the course became devious. The shipwas blocked at one point by a wedge-shaped piece of floe, but weput the ice-anchor through it, towed it astern, and proceededthrough the gap. Steering under these conditions required muscleas well as nerve. There was a clatter aft during the afternoon,and Hussey, who was at the wheel, explained that: "The wheelspun round and threw me over the top of it." The noon positionwas lat. 62 [degrees] 13' S., long. 18 [degrees] 53' W., and the run forthe preceding twenty-four hours had been 32 miles in a south-westerlydirection. We saw three blue whales during the day and oneemperor penguin, a 58-lb. bird, which was added to the larder.

The morning of December 18 found the Endurance proceedingamongst large floes with thin ice between them. The leads werefew. There was a northerly breeze with occasional snow-flurries.We secured three crab-eater seals--two cows and a bull. Thebull was a fine specimen, nearly white all over and 9 ft. 3 in.long; he weighed 600 lb. Shortly before noon further progresswas barred by heavy pack, and we put an ice-anchor on the floeand banked the fires. I had been prepared for evil conditions inthe Weddell Sea, but had hoped that in December and January,at any rate, the pack would be loose, even if no open water wasto be found. What we were actually encountering was fairlydense pack of a very obstinate character. Pack-ice might be describedas a gigantic and interminable jigsaw puzzle devised bynature. The parts of the puzzle in loose pack have floatedslightly apart and become disarranged; at numerous places theyhave pressed together again; as the pack gets closer the congestedareas grow larger and the parts are jammed harder till finally itbecomes "close pack," when the whole of the jigsaw puzzle becomesjammed to such an extent that it can with care and labourbe traversed in every direction on foot. Where the parts do notfit closely there is, of course, open water, which freezes over in afew hours after giving off volumes of "frost-smoke." In obedienceto renewed pressure this young ice "rafts," so formingdouble thicknesses of a toffee-like consistency. Again the opposingedges of heavy floes rear up in slow and almost silent conflict,till high "hedgerows" are formed round each part of the puzzle.At the junction of several floes chaotic areas of piled-up blocksand masses of ice are formed. Sometimes 5-ft. to 6-ft. piles ofevenly shaped blocks of ice are seen so neatly laid that it seemsimpossible for them to be Nature's work. Again, a winding canyonmay be traversed between icy walls 6 ft. to 10 ft. high, or adome may be formed that under renewed pressure bursts upwardlike a volcano. All through the winter the drifting pack changes--grows by freezing, thickens by rafting, and corrugates by pressure.If, finally, in its drift it impinges on a coast, such as thewestern shore of the Weddell Sea, terrific pressure is set up andan inferno of ice-blocks, ridges, and hedgerows results, extendingpossibly for 150 or 200 miles off shore. Sections of pressure icemay drift away subsequently and become embedded in new ice.

I have given this brief explanation here in order that the readermay understand the nature of the ice through which we pushedour way for many hundreds of miles. Another point that mayrequire to be explained was the delay caused by wind while wewere in the pack. When a strong breeze or moderate gale wasblowing the ship could not safely work through any except youngice, up to about two feet in thickness. As ice of that nature neverextended for more than a mile or so, it followed that in a galein the pack we had always to lie to. The ship was 3 ft. 3 in.down by the stern, and while this saved the propeller and ruddera good deal, it made the Endurance practically unmanageablein close pack when the wind attained a force of six miles an hourfrom ahead, since the air currents had such a big surface forwardto act upon. The pressure of wind on bows and the yards of theforemast would cause the bows to fall away, and in these conditionsthe ship could not be steered into the narrow lanes and leadsthrough which we had to thread our way. The falling away ofthe bows, moreover, would tend to bring the stern against theice, compelling us to stop the engines in order to save the propeller.Then the ship would become unmanageable and driftaway, with the possibility of getting excessive sternway on her andso damaging rudder or propeller, the Achilles' heel of a ship inpack-ice.

While we were waiting for the weather to moderate and the iceto open, I had the Lucas sounding-machine rigged over the rudder-trunkand found the depth to be 2810 fathoms. The bottomsample was lost, owing to the line parting 60 fathoms from theend. During the afternoon three adelie penguins approached theship across the floe while Hussey was discoursing sweet music onthe banjo. The solemn-looking little birds appeared to appreciate"It's a Long Way to Tipperary," but they fled in horror whenHussey treated them to a little of the music that comes fromScotland. The shouts of laughter from the ship added to theirdismay, and they made off as fast as their short legs would carrythem. The pack opened slightly at 6.15 p.m., and we proceededthrough lanes for three hours before being forced to anchor to afloe for the night. We fired a Hjort mark harpoon, No. 171, intoa blue whale on this day.

The conditions did not improve during December 19. A freshto strong northerly breeze brought haze and snow, and afterproceeding for two hours the Endurance was stopped again byheavy floes. It was impossible to manoeuvre the ship in the iceowing to the strong wind, which kept the floes in movement andcaused lanes to open and close with dangerous rapidity. The noonobservation showed that we had made six miles to the south-east inthe previous twenty-four hours. All hands were engaged duringthe day in rubbing shoots off our potatoes, which were found to besprouting freely. We remained moored to a floe over the followingday, the wind not having moderated; indeed, it freshened to agale in the afternoon, and the members of the staff and crew tookadvantage of the pause to enjoy a vigorously contested game offootball on the level surface of the floe alongside the ship. Twelvebergs were in sight at this time. The noon position was lat. 62 [degrees]42' S., long. 17 [degrees] 54' W., showing that we had drifted about sixmiles in a north-easterly direction.

Monday, December 21, was beautifully fine, with a gentle west-north-westerlybreeze. We made a start at 3 a.m. and proceededthrough the pack in a south-westerly direction. At noon we hadgained seven miles almost due east, the northerly drift of the packhaving continued while the ship was apparently moving to thesouth. Petrels of several species, penguins, and seals were plentiful,and we saw four small blue whales. At noon we entered along lead to the southward and passed around and between ninesplendid bergs. One mighty specimen was shaped like the Rockof Gibraltar but with steeper cliffs, and another had a naturaldock that would have contained the Aquitania. A spur of iceclosed the entrance to the huge blue pool. Hurley brought outhis kinematograph-camera in order to make a record of thesebergs. Fine long leads running east and south-east among bergswere found during the afternoon, but at midnight the ship wasstopped by small, heavy ice-floes, tightly packed against an unbrokenplain of ice. The outlook from the mast-head was not encouraging.The big floe was at least 15 miles long and 10 mileswide. The edge could not been seen at the widest part, and thearea of the floe must have been not less than 150 square miles.It appeared to be formed of year-old ice, not very thick and withvery few hummocks or ridges in it. We thought it must havebeen formed at sea in very calm weather and drifted up fromthe south-east. I had never seen such a large area of unbrokenice in the Ross Sea.

We waited with banked fires for the strong easterly breeze tomoderate or the pack to open. At 6.30 p.m. on December 22,some lanes opened and we were able to move towards the southagain. The following morning found us working slowly throughthe pack, and the noon observation gave us a gain of 19 milesS. 41 [degrees] W. for the seventeen and a half hours under steam. Manyyear-old adelies, three crab-eaters, six sea-leopards, one Weddelland two blue whales were seen. The air temperature, which had been downto 2.5 [degrees] Fahr. on December 21, had risen to 34 [degrees] Fahr.While we were working along leads to the southward in the afternoon,we counted fifteen bergs. Three of these were table-topped,and one was about 70 ft. high and 5 miles long. Evidentlyit had come from a barrier-edge. The ice became heavierbut slightly more open, and we had a calm night with fine longleads of open water. The water was so still that new ice wasforming on the leads. We had a run of 70 miles to our credit atnoon on December 24, the position being lat. 64 [degrees] 39' S., long.17 [degrees] 17' W. All the dogs except eight had been named. I do not knowwho had been responsible for some of the names, which seemed torepresent a variety of tastes. They were as follows: Rugby,Upton, Bristol, Millhill, Songster, Sandy, Mack, Mercury, Wolf,Amundsen, Hercules, Hackenschmidt, Samson, Sammy, Skipper,Caruso, Sub, Ulysses, Spotty, Bosun, Slobbers, Sadie, Sut, Sally,Jasper, Tim, Sweep, Martin, Splitlip, Luke, Saint, Satan, Chips,Stumps, Snapper, Painful, Bob, Snowball, Jerry, Judge, Sooty,Rufus, Sidelights, Simeon, Swanker, Chirgwin, Steamer, Peter,Fluffy, Steward, Slippery, Elliott, Roy, Noel, Shakespeare,Jamie, Bummer, Smuts, Lupoid, Spider, and Sailor. Some ofthe names, it will be noticed, had a descriptive flavour.

Heavy floes held up the ship from midnight till 6 a.m. on December25, Christmas Day. Then they opened a little and wemade progress till 11.30 a.m., when the leads closed again. Wehad encountered good leads and workable ice during the earlypart of the night, and the noon observation showed that our runfor the twenty-four hours was the best since we entered the packa fortnight earlier. We had made 71 miles S. 4[degrees] W. The iceheld us up till the evening, and then we were able to followsome leads for a couple of hours before the tightly packed floesand the increasing wind compelled a stop. The celebration ofChristmas was not forgotten. Grog was served at midnight to allon deck. There was grog again at breakfast, for the benefit ofthose who had been in their bunks at midnight. Lees had decoratedthe wardroom with flags and had a little Christmas presentfor each of us. Some of us had presents from home to open.Later there was a really splendid dinner, consisting of turtle-soup,whitebait, jugged hare, Christmas pudding, mince-pies, dates,figs, and crystallized fruits, with rum and stout as drinks. Inthe evening everybody joined in a" sing-song." Hussey had madea one-stringed violin, on which, in the words of Worsley, he "discoursedquite painlessly." The wind was increasing to a moderatesouth-easterly gale and no advance could be made, so wewere able to settle down to the enjoyments of the evening.

The weather was still bad on December 26 and 27, and the Enduranceremained anchored to a floe. The noon position on the 26th waslat. 65 [degrees] 43' S., long. 17 [degrees] 36' W. We made anothersounding on this day with the Lucas machine and found bottomat 2819 fathoms. The specimen brought up was a terriginousblue mud (glacial deposit) with some radiolaria. Every onetook turns at the work of heaving in, two men working togetherin ten-minute spells.

Sunday, December 27, was a quiet day aboard. The southerlygale was blowing the snow in clouds off the floe and the temperaturehad fallen to 23 [degrees] Fahr. The dogs were having an uncomfortabletime in their deck quarters. The wind had moderatedby the following morning, but it was squally with snow-flurries,and I did not order a start till 11 p.m. The pack was still close,but the ice was softer and more easily broken. During the pausethe carpenter had rigged a small stage over the stern. A manwas stationed there to watch the propeller and prevent it strikingheavy ice, and the arrangement proved very valuable. It savedthe rudder as well as the propeller from many blows.

The high winds that had prevailed for four and a half daysgave way to a gentle southerly breeze in the evening of December29. Owing to the drift we were actually eleven miles furthernorth than we had been on December 25. But we made fairlygood progress on the 30th in fine, clear weather. The ship followeda long lead to the south-east during the afternoon andevening, and at 11 p.m. we crossed the Antarctic Circle. Anexamination of the horizon disclosed considerable breaks in thevast circle of pack-ice, interspersed with bergs of different sizes.Leads could be traced in various directions, but I looked in vainfor an indication of open water. The sun did not set that night,and as it was concealed behind a bank of clouds, we had a glow ofcrimson and gold to the southward, with delicate pale green reflectionsin the water of the lanes to the south-east.

The ship had a serious encounter with the ice on the morningof December 31. We were stopped first by floes closing aroundus, and then about noon the Endurance got jammed between twofloes heading east-north-east. The pressure heeled the ship oversix degrees while we were getting an ice-anchor on to the floe inorder to heave astern and thus assist the engines, which were runningat full speed. The effort was successful. Immediately afterwards,at the spot where the Endurance had been held, slabs ofice 50 ft. by 15 ft. and 4 ft. thick were forced ten or twelve feetup on the lee floe at an angle of 45 degrees. The pressure wassevere, and we were not sorry to have the ship out of its reach.The noon position was lat. 66 [degrees] 47' S., long. 15 [degrees] 52' W., and therun for the preceding twenty-four hours was 51 miles S. 29 [degrees] E.

"Since noon the character of the pack has improved," wroteWorsley on this day. "Though the leads are short, the floes arerotten and easily broken through if a good place is selected withcare and judgment. In many cases we find large sheets of youngice through which the ship cuts for a mile or two miles at astretch. I have been conning and working the ship from thecrow's-nest and find it much the best place, as from there one cansee ahead and work out the course beforehand, and can also guardthe rudder and propeller, the most vulnerable parts of a ship inthe ice. At midnight, as I was sitting in the `tub,' I heard aclamorous noise down on the deck, with ringing of bells, andrealized that it was the New Year." Worsley came down fromhis lofty seat and met Wild, Hudson, and myself on the bridge,where we shook hands and wished one another a happy and successfulNew Year. Since entering the pack on December 11 wehad come 480 miles through loose and close pack-ice. We hadpushed and fought the little ship through, and she had stood thetest well, though the propeller had received some shrewd blowsagainst hard ice and the vessel had been driven against the floeuntil she had fairly mounted up on it and slid back rolling heavilyfrom side to side. The rolling had been more frequently causedby the operation of cracking through thickish young ice, wherethe crack had taken a sinuous course. The ship, in attemptingto follow it, struck first one bilge and then the other, causing herto roll six or seven degrees. Our advance through the pack hadbeen in a S. 10 [degrees] E. direction, and I estimated that the totalsteaming distance had exceeded 700 miles. The first 100 mileshad been through loose pack, but the greatest hindrances had beenthree moderate south-westerly gales, two lasting for three dayseach and one for four and a half days. The last 250 miles hadbeen through close pack alternating with fine long leads andstretches of open water.

During the weeks we spent manoeuvring to the south throughthe tortuous mazes of the pack it was necessary often to splitfloes by driving the ship against them. This form of attack waseffective against ice up to three feet in thickness, and the processis interesting enough to be worth describing briefly. When theway was barred by a floe of moderate thickness we would drivethe ship at half speed against it, stopping the engines just beforethe impact. At the first blow the Endurance would cut aV-shaped nick in the face of the floe, the slope of her cutwateroften causing her bows to rise till nearly clear of the water, whenshe would slide backwards, rolling slightly. Watching carefullythat loose lumps of ice did not damage the propeller, we wouldreverse the engines and back the ship off 200 to 300 yds. Shewould then be driven full speed into the V, taking care to hit thecentre accurately. The operation would be repeated until a shortdock was cut, into which the ship, acting as a large wedge, wasdriven. At about the fourth attempt, if it was to succeed at all,the floe would yield. A black, sinuous line, as though pen-drawnon white paper, would appear ahead, broadening as the eye tracedit back to the ship. Presently it would be broad enough to receiveher, and we would forge ahead. Under the bows and alongside,great slabs of ice were being turned over and slid back on thefloe, or driven down and under the ice or ship. In this way theEndurance would split a 2-ft. to 3-ft. floe a square mile in extent.Occasionally the floe, although cracked across, would be so held byother floes that it would refuse to open wide, and so graduallywould bring the ship to a stand-still. We would then go asternfor some distance and again drive her full speed into the crack,till finally the floe would yield to the repeated onslaughts.

Continues...

Excerpted from Southby Ernest Henry Shackleton Copyright © 1999 by Ernest Henry Shackleton. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBerkley Books

- Publication date1999

- ISBN 10 0451198808

- ISBN 13 9780451198808

- BindingMass Market Paperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages464

FREE shipping within United Kingdom

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking...

South: the Endurance Expedition

Seller: Goldstone Books, Llandybie, United Kingdom

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. All orders are dispatched within one working day from our UK warehouse. We've been selling books online since 2004! We have over 750,000 books in stock. No quibble refund if not completely satisfied. Seller Inventory # mon0005058729

Quantity: 1 available

South : The Endurance Expedition -- the Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of All Time

Seller: Better World Books Ltd, Dunfermline, United Kingdom

Condition: Good. Ships from the UK. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP89298188

Quantity: 1 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of All Time

Seller: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR002175251

Quantity: 1 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of All Time

Seller: WorldofBooks, Goring-By-Sea, WS, United Kingdom

Paperback. Condition: Fair. A readable copy of the book which may include some defects such as highlighting and notes. Cover and pages may be creased and show discolouration. Seller Inventory # GOR007107509

Quantity: 1 available

South: The Endurance Expedition

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: good. Befriedigend/Good: Durchschnittlich erhaltenes Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit Gebrauchsspuren, aber vollständigen Seiten. / Describes the average WORN book or dust jacket that has all the pages present. Seller Inventory # M00451198808-G

Quantity: 1 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Seller Inventory # G0451198808I3N00

Quantity: 3 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Seller Inventory # G0451198808I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Seller Inventory # G0451198808I3N00

Quantity: 3 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Seller Inventory # G0451198808I3N00

Quantity: 3 available

South: The Endurance Expedition -- The Breathtaking First-Hand Account of One of the Most Astounding Antarctic Adventures of

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Mass Market Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.55. Seller Inventory # G0451198808I3N00

Quantity: 3 available