Items related to Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict...

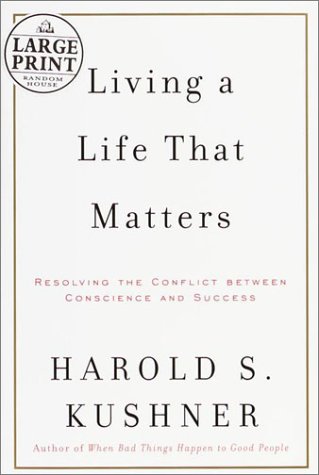

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success (Random House Large Print) - Hardcover

Synopsis

From the author of the huge bestseller When Bad Things Happen to Good People, a profound and practical book about doing well by doing good.

In this timely and compelling book, Harold Kushner addresses our craving for significance, the need to know that our lives and choices mean something. We do great things, and occassionally terrible things, to reassure ourselves that we matter to the world. We sometimes confuse fame, power, and wealth with true achievement. But finally we need to think of ourselves as good people and are troubled when we compromise our integrity to be successful and important.

Rabbi Kushner suggests that the path to a truly successful and significant life lies in friendship, family, acts of generosity and self-sacrifice, as well as God's forgiving nature. He describes how, in changing the life of even one person in a positive way, we make a difference in the world, give our lives meaning, and prove that we do in fact matter.

Persuasive and sympathetic, anecdotal and commonsensical, Living a Life that Matters inspires and uplifts.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Harold S. Kushner is the author of several bestselling books on coping with life's challenges. He has been honored by the Christophers as one of the fifty people who have made the world a better place. He is Rabbi Laureate of Temple Israel in Natick, Massachusetts.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Living a Life That Matters

How to Resolve the Conflict Between Conscience and SuccessBy Harold S. KushnerRandom House Large Print Publishing

Copyright © 2001 Harold S. KushnerAll right reserved.

ISBN: 0375431373

Chapter One

The Two Voices of God Like many people, I live in two worlds. Much of the time,I live in the world of work and commerce, eating, working, and paying my bills.It is a world that honors people for being attractive and productive. It revereswinners and scorns losers, as reflected in its treatment of devoted publicservants who lose an election or in the billboard displayed at the AtlantaOlympic Games a few years ago: "You don't win the silver medal, you losethe gold." As in most contests, there are many more losers than winners, somost of the citizens of that world spend a lot of time worrying that they don'tmeasure up.

But, fortunately, there is another world where, even before I entered itprofessionally, I have spent some of my time. As a religiously committed person,I live in the world of faith, the world of the spirit. Its heroes are models ofcompassion rather than competition. In that world, you win through sacrifice andself-restraint. You win by helping your neighbor and sharing with him ratherthan by finding his weakness and defeating him. And in the world of the spirit,there are many more winners than losers.

When I was young, most of my time and energy were devoted to the world ofgetting and spending. I relished competition. I wanted to be challenged. Howelse could I find out how good I was, where I stood on the ladder of winners andlosers? I was living out the insight of the psychoanalyst Carl Jung that"act one of a young man's life is the story of his setting out to conquerthe world."

Of course, I was not the only person who did that. Most people lived as I did.For several years, our next-door neighbor's son was a nationally renownedprofessional athlete. It wasn't money that kept him playing and risking seriousinjury. It was the challenge, the competition, the opportunity to prove onceagain that he was better than most people at what he did.

When I was young, I saw that second world, the world of faith, as a kind ofvacation home, a place to which I repaired in order to relax from the stress ofthe world of striving, so that I could emerge refreshed to resume the battle. Attimes, it seemed almost a mirror image of my first world, a place wheredifferent people played by different rules. Old people were respected there fortheir wisdom and experience, as were old ideas and old values. People weredescribed as "beautiful" because they exuded compassion and generosityrather than wealth and glamour. "Success" had a very different meaningthere.

As my life increasingly became a story of giving up dreams and coming to termswith my limitations (Jung went on to say, "Act two is the story of a youngman realizing that the world is not about to be conquered by the likes ofhim"), I found myself returning more and more to that second, alternativeworld. I would often recall the words of my teacher Abraham Joshua Heschel:"When I was young, I admired clever people. As I grew old, I came to admirekind people."

Looking back at my life, I realize that I was commuting between those two worldsin an effort to meet two basic human needs, the need to feel successful andimportant and the need to think of myself as a good person, someone who deservedthe approval of other good people.

We need to know that we matter to the world, that the world takes us seriously.I read a memoir recently in which a woman recalls staying home from school oneday as a child because she was sick. Hearing the noises of the world outside herwindow, she was dismayed to realize that the world was going on without her, noteven missing her. The woman grew up to be devoutly religious, a pillar of herchurch, active in many organizations, picketing abortion clinics, feeding thehungry. As I read her story, I wondered if she became an activist to overcomethat childhood fear of insignificance, to reassure herself that she did make adifference to the world.

In my forty years as a rabbi, I have tended to many people in the last momentsof their lives. Most of them were not afraid of dying. Some were old and feltthat they had lived long, satisfying lives. Others were so sick and in such painthat only death would release them. The people who had the most trouble withdeath were those who felt that they had never done anything worthwhile in theirlives, and if God would only give them another two or three years, maybe theywould finally get it right. It was not death that frightened them; it wasinsignificance, the fear that they would die and leave no mark on the world.

The need to feel important drives people to place enormous value on such symbolsas titles, corner offices, and first-class travel. It causes us to feelexcessively pleased when someone important recognizes us, and to feel hurt whenour doctor or pastor passes us on the street without saying hello, or when aneighbor calls us by our sister's or brother's name. The need to know that weare making a difference motivates doctors and medical researchers to spend hourslooking through microscopes in the hope of finding cures for diseases. It drivesinventors and entrepreneurs to stay up nights trying to find a better way ofproviding people with something they need. It causes artists, novelists, andcomposers to try to add to the store of beauty in the world by finding just theright color, the right word, the right note. And it leads ordinary people to buysix copies of the local paper because it has their name or picture in it.

Because we find ourselves in so many settings that proclaim ourinsignificance—in stores where salespeople don't know our name and don't careto know it, in crowded buses and airplanes that give us the message that if weweren't there someone else would be available to take our place—some people dodesperate things to reassure themselves that they matter to the world. I canbelieve that Lee Harvey Oswald shot President Kennedy and that John Hinckley,Jr., tried to kill President Reagan in large measure to prove that the world waswrong in not taking them seriously. They had the power to change history. At aless crucial level, there are people who confuse notoriety with celebrity, andcelebrity with importance. They go to extreme lengths to get their names in theGuinness Book of Records, or to appear on daytime television shows, revealingthings about themselves and their families that most of us would be embarrassedto reveal to our clergyman or our closest friends. They may come across aspitiable; the audience may scorn them. But for one hour their story holds theattention of millions of Americans. They matter.

At the same time, we need to be assured that we are good people. A few yearsago, I wrote a book entitled How Good Do We Have to Be? Its basicmessage was that God does not expect perfection from us, so we should not demandperfection of ourselves or those around us, for God knows what a complicatedstory a human life is and loves us despite our inevitable lapses. As I traveledaround the country talking about my book, something interesting kept happening.Although most people in my audience welcomed the message that God loved themdespite their mistakes and failings, in every audience there would be asignificant number of people who were uncomfortable with it. They wanted tobelieve that God loved them, and other people loved them, because they deservedit, not because God and the other people in their lives were gracious enough toput up with them. They wanted to believe that God cared about the choices theymade every day, choosing between selfishness and generosity, between honesty anddeceitfulness, and that the world became a better place when they made the rightchoices. They were like the college student who hands in a paper and wants theprofessor to read it carefully and critically, because he or she has worked sohard to make it good. The people in my audience felt that they had worked hardto lead moral lives. They might hope that God would make allowances for humanfrailty, but, like the college student, they would be sorely disappointed by theresponse, That's all right, I really didn't expect much from you anyway.

My answer to them when they challenged me was that I believe God speaks to us intwo voices.

One is the stern, commanding voice issuing from the mountaintop, thundering"Thou shalt not!," summoning us to be more, to reach higher, to demandgreater things of ourselves, forbidding us to use the excuse "I'm onlyhuman," because to be human is a wondrous thing.

God's other voice is the voice of compassion and forgiveness, an embracing,cleansing voice, assuring us that when we have aimed high and fallen short weare still loved. God understands that when we give in to temptation it is atemporary lapse and does not reflect our true character.

Some years ago, Erich Fromm wrote a little book entitled The Art ofLoving, in which he distinguished between what he called "motherlove" and "father love" (emphasizing that people of either genderare capable of both kinds of love). Mother love says: You are bone of my boneand flesh of my flesh, and I will always love you no matter what. Nothing youever do or fail to do will make me stop loving you. Father love says: I willlove you if you earn my love and respect, if you get good grades, if you makethe team, if you get into a good college, earn a good salary.

Fromm insists that every one of us needs to experience both kinds of loving. Itmay seem at first glance that mother love is good, warm, and freely given,father love harsh and conditional (I will only love you if . . .). But as myaudiences taught me, and as a moment's reflection might teach us all, sometimeswe want to hear the father's message that we are loved because we deserve it,not only because the other person is so generous and tolerant.

People need to hear the same message from God that children need to hear fromtheir earthly parents. Just as it is an unforgettably comforting and necessaryexperience for a child caught doing something wrong to be forgiven and to learnthat parental love is a gift that will not be arbitrarily withdrawn, a lesson nochild should grow up without absorbing, so is it a vital part of everyone'sreligious upbringing to learn that God's love is not tentative, that ourfailures do not alienate us from God. That is why Roman Catholic churches offerthe sacrament of confession and penance, why Protestant liturgy emphasizes thatthe church is a home for imperfect people, and why Yom Kippur, the Day ofAtonement for our sins, is the holiest day of the Jewish calendar.

When we are feeling burdened by guilt, when we know that we have done wrong andhate ourselves for it, we need to hear the voice of God-as-mother, assuring usthat nothing can alienate us from God's love. But when we have worked hard to begood, honest, generous people, there is something lacking in the message, I loveyou despite yourself because I am so loving and lenient. What is missing is thevoice of God-as-father: You're good, you have earned My love.

I can't tell you how many men and women I have counseled who spent their entireadult lives feeling somehow incomplete and unsure of their worth because theynever heard their father tell them, You're good and I love you for it. I oncepaid a condolence call on a man in my congregation whose father had just died.The funeral and memorial week had taken place in another city, where his parentshad lived, and I was the only visitor on his first night home. After severalminutes of asking about the funeral and how his mother was coping, I foundmyself saying, "It sounds like your father was a man who kept his emotionsto himself."

The congregant broke down and started to cry. "He never said anything goodabout me. All my life, I wanted to hear him say he was proud of me for who I wasand what I was doing, and all I ever got from him was this sense that he showedhis love by putting up with me." He wiped his eyes, apologized for thetears, and went on. "In my head, I know that he had a problem talking abouthis feelings. In my head, I know he thought his way was the right way to make medo better. But in my heart, I feel so cheated. I always got good grades inschool, never got into trouble, went to a good college. I make a good living,live in a nice home, have a wonderful family. Would it have been so hard for himjust once to tell me that he was proud of me? And now he's dead and I'll neverhear it!"

I tried to tell him that the problem was his father's, not his, that his fatherwas part of an older generation of men who had trouble knowing what they werefeeling, let alone putting it into words. I reminded him that his father hadgrown up in the 1930s, during the hard years of the Depression, and had probablybeen forced by circumstance to grow a hard outer shell over his sensitive innercore, because sensitive, caring people were often left behind in those years. Iprompted him to remember all the nonverbal ways in which his father had shownlove and concern for him. But I don't know how much that helped. My congregantmay be a permanent member of that army of men and women who will always feel alittle bit incomplete because they never got the message of father love—I loveyou for what you have made of yourself—and will keep on working and strugglinguntil someone they care about tells them that.

People need to hear the message that they are good. And people who are notentirely sure of their goodness may need that validation even more. That may bewhy churches and synagogues attract people who are bothered by the lapses intheir behavior as husbands and wives, as parents, and as children of agingparents, and crave the reassurance that they are welcome in God's house. Thatmay be why a wealthy businessman cherishes a twenty-five-dollar plaque given himby his church, synagogue, or lodge for being honored as Man of the Year. It mayexplain why we do things that don't benefit us economically but benefit uspsychologically, giving charity, volunteering for good causes. We do them tonourish our self-image as generous, caring people. I have met many people whojoined the local Rotary Club or Young Presidents Organization to make usefulcontacts, but stayed and became active because they came to enjoy the feeling ofmaking their community a better place. And it may be why we make excuses for thethings we do that embarrass us. How do most of us handle our mistakes? We blameothers, we blame our upbringing, we rationalize what we did, in an effort toreassure ourselves of our essential goodness. (Our rationalizations do seemaimed at ourselves; they rarely persuade anyone else.) In his book ThreeSeductive Ideas, Dr. Jerome Kagan, professor of psychology at Harvard, writes,"The desire to believe that the self is ethically worthy . . . isuniversal." He points out that children as young as two years old evaluatetheir behavior in terms of right and wrong and need to think of themselves asgood. Without that innate moral sense, Kagan believes, children could not besocialized.

We tend to assume that people who violate the law in a serious way—violentcriminals, gang members, bank robbers—are immoral people, people who don't careabout society's rules or what others think of them. But a psychologist friend ofmine who has spent time working with prisoners in a federal penitentiary learnedsomething different. He told me that when he started he assumed that he would bedealing with hardened criminals, people who were indifferent to moralobligations and considerations of right and wrong. To his surprise, he learnedthat prison inmates hold to a very strict moral code. It may not be our moralcode; it may not be a moral code we would find admirable or even acceptable. Butin the prison setting, there is behavior for which you gain approval (notratting on associates) and there is behavior that sinks you to the bottom of themoral pecking order (imprisonment for hurting women or children). Similarly,gang members may appear to us as having total disregard for moral considerationsand public opinion, but within the gang, they will risk injury and hardship tolive up to its rules. Apparently, even people on the fringes of society (or wellbeyond the fringe) cannot bear to think of themselves as bad people. They willinsist on their innocence, they will blame the circumstances of their growingup, or they will defend the morality of what they do. In Mario Puzo's novelThe Godfather, Michael Corleone says of his father, Don Vito, "Heoperates on a code of ethics he considers far superior to the legal stricturesof society."

We human beings are such complicated creatures. We have so many needs, so manyemotional hungers, and they often come into conflict with each other. Ourimpulse to help needy people or support medical research conflicts with ourdesire to have the money to buy all the things we are attracted to. Mycommitment to doing the right thing impels me to want to apologize to people Ihave offended, but my desire to protect my image and nourish my sense ofrighteousness persuades me that the problem is their hypersensitivity, not mybehavior. What happens when our need to think of ourselves as good peoplecollides with our need to be recognized as important? Is it possible to do both?How often do we find ourselves betraying our values, violating our consciences,in our struggle to have an impact on the world? Political candidates compromisetheir values to raise funds and gain votes. Salesmen exaggerate the virtues oftheir wares. Doctors, lawyers, and businessmen neglect their families in thepursuit of professional and financial success. Often we don't like what we findourselves doing (although it is remarkable how easily we get used to it afterthe first few times), but we tell ourselves we have no choice. That is the kindof world we live in, and that is the price we have to pay for claiming our spacein it.

This may well be the central dilemma in the lives of many of us. Wewant—indeed, we need—to think of ourselves as good people, though from time totime we find ourselves doing things that make us doubt our goodness. We dream ofleaving the world a better place for our having passed through it, though weoften wonder whether, in our quest for significance, we litter the world withour mistakes more than we bless it with our accomplishments. Our souls aresplit, part of us reaching for goodness, part of us chasing fame and fortune anddoing questionable things along the way, as we realize that those two paths maydiverge sharply. Our self-image is like an out-of-focus photograph, two slightlyblurred images instead of one clear one. Much of our lives, much of our energywill be devoted to closing that gap between the longings of our soul and thescoldings of our conscience, between our too-often conflicting needs for theassurance of knowing that we are good and the satisfaction of being told that weare important.

The people we find ourselves admiring most tend to be people who strike us ashaving closed that gap, having resolved that conflict. Many of the biographieswe read, and especially the life story to which we will turn in the nextchapter, are accounts of people struggling to reconcile those two longings, tobe good and to matter. We examine their lives, not only to gain information butto gain insight as to how they managed to do that, in the hope that we too willbe able to gain the two prizes for which our souls yearn.

Continues...

Excerpted from Living a Life That Mattersby Harold S. Kushner Copyright © 2001 by Harold S. Kushner. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict...

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. Acceptable dust jacket. Large Print edition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Seller Inventory # M03G-05869

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters : How to Resolve the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Lrg. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 7879094-75

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters : How to Resolve the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Lrg. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3223172-20

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success, Large Print Edition

Seller: BookDepart, Shepherdstown, WV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: UsedGood. Hardcover; surplus library copy with the usual stampings; refere nce number taped to dust jacket spine; otherwise in good condition with clean text, firm binding. Dust jacket, light fading, protected by a Mylar cover. Seller Inventory # 21543

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_441783837

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success Large Print Edition

Seller: Tacoma Book Center, Tacoma, WA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Later Edition. ISBN 0375431373. Hardback. Very Good condition book in a Very Good condition dustjacket with minor rubs and creases around its edges. Tight, sound, unmarked copy. $22.00 original price is present and unclipped on front flap of dustjacket. Large Print Edition. Seller Inventory # 99133942

Quantity: 1 available

LIVING A LIFE THAT MATTERS : Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: 100POCKETS, Berkeley, CA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: NEW - COLLECTIBLE. Dust Jacket Condition: New. First Edition, First Printing. BRAND NEW & COLLECTIBLE. Large Print, First Edition, First Printing. Rewarding spiritual dialogue addressing rewarding life. Rabbi laureate of Temple Israel, Natick, MA, Harold S. Kushner is known for When Bad Things Happen to Good People. In this volume the Rabbi draws on annecdotes from his congregation, literature, current events and the Biblical story of Jacob (a worldly trickster who evolves into a man of God), Rabbi Kushner speaks of some persistent dilemmas confronting the human condition ---- Why do we so often violate our own moral standards? How can we pursue justice without giving in to the lure of revenge and retribution.? Persuasive, sympathetic guidelines towards balancing the conscience while in pursuit of worldly success. Written with humanity and warmth. Seller Inventory # 018130

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters: Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: The Book Spot, Sioux Falls, MN, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks67292

Quantity: 1 available

Living a Life That Matters : Resolving the Conflict Between Conscience and Success

Seller: Alhambra Books, Edmonton, AB, Canada

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. Large Print Edition. 225 pp. Seller Inventory # 053084

Quantity: 1 available