Synopsis

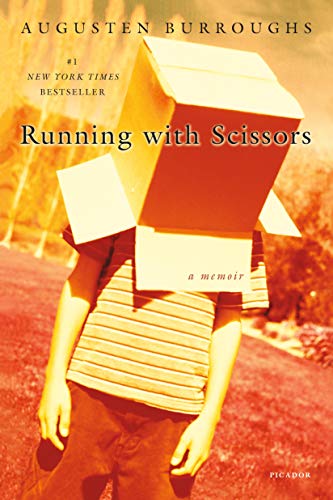

The #1 New York Times bestselling memoir from Augusten Burroughs, Running with Scissors, now a Major Motion Picture!

Running with Scissors is the true story of a boy whose mother (a poet with delusions of Anne Sexton) gave him away to be raised by her psychiatrist, a dead-ringer for Santa and a lunatic in the bargain. Suddenly, at age twelve, Augusten Burroughs found himself living in a dilapidated Victorian in perfect squalor. The doctor's bizarre family, a few patients, and a pedophile living in the backyard shed completed the tableau. Here, there were no rules, there was no school. The Christmas tree stayed up until summer, and Valium was eaten like Pez. And when things got dull, there was always the vintage electroshock therapy machine under the stairs....

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Augusten Burroughs is the author of Running with Scissors, Dry, Magical Thinking: True Stories, Possible Side Effects, A Wolf at the Table and You Better Not Cry. He is also the author of the novel Sellevision, which has been optioned for film. The film version of Running with Scissors, directed by Ryan Murphy and produced by Brad Pitt, was released in October 2006 and starred Joseph Cross, Brian Cox, Annette Bening (nominated for a Golden Globe for her role), Alec Baldwin and Evan Rachel Wood. Augusten's writing has appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers around the world including The New York Times and New York Magazine. In 2005 Entertainment Weekly named him one of "The 25 Funniest People in America." He resides in New York City and Western Massachusetts.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Running with Scissors

By Augusten BurroughsPicador USA

Copyright ©2003 Augusten BurroughsAll right reserved.

ISBN: 9780312422271

Chapter One

SOMETHING ISN'T RIGHTMy mother is standing in front of the bathroom mirrorsmelling polished and ready; like Jean Nati, Dippity Doand the waxy sweetness of lipstick. Her white, handgun-shapedblow-dryer is lying on top of the wicker clothes hamper,ticking as it cools. She stands back and smoothes herhands down the front of her swirling, psychedelic Pucci dress,biting the inside of her cheek.

"Damn it," she says, "something isn't right."

Yesterday she went to the fancy Chopping Block salon inAmherst with its bubble skylights and ficus trees in chromeplanters. Sebastian gave her a shag.

"That hateful Jane Fonda," she says, fluffing her dark brownhair at the crown. "She makes it look so easy." She pinchesher sideburns into points that accentuate her cheekbones.People have always said she looks like a young Lauren Bacall,especially in the eyes.

I can't stop staring at her feet, which she has slipped intotreacherously tall red patent-leather pumps. Because she normallylives in sandals, it's like she's borrowed some other lady'sfeet. Maybe her friend Lydia's feet. Lydia has teased black hair,boyfriends and an above-ground pool. She wears high heelsall the time, even when she's just sitting out back by the poolin her white bikini, smoking menthol cigarettes and talkingon her olive-green Princess telephone. My mother only wearsfancy shoes when she's going out, so I've come to associatethem with a feeling of abandonment and dread.

I don't want her to go. My umbilical cord is still attachedand she's pulling at it. I feel panicky.

I'm standing in the bathroom next to her because I needto be with her for as long as I can. Maybe she is going toHartford, Connecticut. Or Bradley Field International Airport.I love the airport, the smell of jet fuel, flying south tovisit my grandparents.

I love to fly.

When I grow up, I want to be the one who opens thosecabinets above the seats, who gets to go into the small kitchenwhere everything fits together like a shiny silver puzzle. Plus,I like uniforms and I would get to wear one, along with awhite shirt and a tie, even a tie-tack in the shape of airplanewings. I would get to serve peanuts in small foil packets andoffer people small plastic cups of soda. "Would you like thewhole can?" I would say. I love flying south to visit my grandparentsand I've already memorized almost everything theseflight attendants say. "Please make sure that you have extinguishedall smoking materials and that your tray table is in itsupright and locked position." I wish I had a tray table in mybedroom and I wish I smoked, just so I could extinguish mysmoking materials.

"Okay, I see what's the matter," my mother says. She turnsto me and smiles. "Augusten, hand me that box, would you?"

Her long, frosted beige nail points to the box of Kotex maxipads on the floor next to the toilet bowl. I grab the box andhand it to her.

She takes two pads from the box and sets it on the floorat her feet. I notice that the box is reflected in the side of hershoe, like a small TV. Carefully, she peels the paper strip offthe back of one of the pads and slides it through the neck ofher dress, placing it on top of her left shoulder. She smoothesthe silk over the pad and puts another one on the right side.She stands back.

"What do you think of that!" she says. She is delightedwith herself. It's as if she has drawn a picture and placed iton her own internal refrigerator door.

"Neat," I say.

"You have a very creative mother," she says. "Instant shoulderpads."

The blow-dryer continues to tick like a clock, countingdown the seconds. Hot things do that. Sometimes when myfather or mother comes home, I will go down and stand nearthe hood of the car to listen to it tick, moving my face inclose to feel the heat.

"Are you coming upstairs with me?" she says. She takes hercigarette from the clamshell ashtray on the back of the toilet.My mother loves frozen baked stuffed clams, and she saves theshells to use as ashtrays, stashing them around the house.

I am fixated on the dryer. The vent holes on the side havehairs stuck in them, small hairs and white lint. What is lint?How does it find hair dryers and navels? "I'm coming."

"Turn off the light," she says as she walks away, creating asmall whoosh that smells sweet and chemical. It makes me sadbecause it's the smell she makes when she's leaving.

"Okay," I say. The orange light from the dehumidifier thatsits next to the wicker laundry hamper is looking at me, andI look back at it. Normally it would terrify me, but becausemy mother is here, it is okay. Except she is walking fast, hasalready walked halfway across the family room floor, is almostat the fireplace, will be turning around the corner and headingup the stairs and then I will be alone in the dark bathroomwith the dehumidifier eye, so I run. I run after her, certainthat something is following me, chasing me, just about tocatch me. I run past my mother, running up the stairs, usingmy legs and my hands, charging ahead on all fours. I make itto the top and look down at her.

She climbs the stairs slowly, deliberately, reminding me ofan actress on the way to the stage to accept her AcademyAward. Her eyes are trained on me, her smile all mine. "Yourun up those stairs just like Cream."

Cream is our dog and we both love her. She is not myfather's dog or my older brother's. She's most of all not myolder brother's since he's sixteen, seven years older than I, andhe lives with roommates in Sunderland, a few miles away. Hedropped out of high school because he said he was too smartto go and he hates our parents and he says he can't stand tobe here and they say they can't control him, that he's "out ofcontrol" and so I almost never see him. So Cream doesn'tbelong to him at all. She is mine and my mother's. She lovesus most and we love her. We share her. I am just like Cream,the golden retriever my mother loves.

I smile back at her.

I don't want her to leave.

Cream is sleeping by the door. She knows my mother isleaving and she doesn't want her to go, either. Sometimes, Iwrap aluminum foil around Cream's middle, around her legsand her tail and then I walk her through the house on a leash.I like it when she's shiny, like a star, like a guest on the Donnieand Marie Show.

Cream opens her eyes and watches my mother, her earstwitching, then she closes her eyes again and exhales heavily.She's seven, but in dog years that makes her forty-nine. Creamis an old lady dog, so she's tired and just wants to sleep.

In the kitchen my mother takes her keys off the table andthrows them into her leather bag. I love her bag. Inside arepapers and her wallet and cigarettes and at the bottom, whereshe never looks, there is loose change, loose mints, specs oftobacco from her cigarettes. Sometimes I bring the bag to myface, open it and inhale as deeply as I can.

"You'll be long asleep by the time I come home," she tellsme. "So good night and I'll see you in the morning."

"Where are you going?" I ask her for the zillionth time.

"I'm going to give a reading in Northampton," she tellsme. "It's a poetry reading at the Broadside Bookstore."

My mother is a star. She is just like that lady on TV,Maude. She yells like Maude, she wears wildly colored gownsand long crocheted vests like Maude. She is just like Maudeexcept my mother doesn't have all those chins under herchins, all those loose expressions hanging off her face. Mymother cackles when Maude is on. "I love Maude," she says.My mother is a star like Maude.

"Will you sign autographs?"

She laughs. "I may sign some books."

My mother is from Cairo, Georgia. This makes everythingshe says sound like it went through a curling iron. Other peoplesound flat to my ear; their words just hang in the air. Butwhen my mother says something, the ends curl.

Where is my father?

"Where is your father?" my mother says, checking herwatch. It's a Timex, silver with a black leather strap. The faceis small and round. There is no date. It ticks so loud that ifthe house is quiet, you can hear it.

The house is quiet. I can hear the ticking of my mother'swatch.

Outside, the trees are dark and tall, they lean in towardthe house, I imagine because the house is bright inside andthe trees crave the light, like bugs.

We live in the woods, in a glass house surrounded by trees;tall pine trees, birch trees, ironwoods.

The deck extends from the house into the trees. You canstand on it and reach and you might be able to pull a leaf offa tree, or a sprig of pine.

My mother is pacing. She is walking through the livingroom, behind the sofa to look out the large sliding glass doordown to the driveway; she is walking around the dining-roomtable. She straightens the cubed glass salt and pepper shakers.She is walking through the kitchen and out the other door ofthe kitchen. Our house is very open. The ceilings are veryhigh. There is plenty of room here. "I need high ceilings," mymother always says. She says this now. "I need high ceilings."She looks up.

There is the sound of gravel crackling beneath tires. Then,lights on the wall, spreading to the ceiling, sliding throughthe room like a living thing.

"Finally," my mother says.

My father is home.

He will come inside the house, pour himself a drink andthen go downstairs and watch TV in the dark.

I will have the upstairs to myself. All the windows and thewalls and the entire fireplace which cuts straight through thecenter of the house, both floors; I will have the ice maker inthe freezer, the hexagonal espresso pot my mother uses forguests, the black deck, the stereo speakers; all of this containedin so much tall space. I will have it all.

I will walk around and turn lights on and off, on and off.There is a panel of switches on the wall before the hall opensup into two huge, tall rooms. I will switch the spotlights onin the living room, illuminating the fireplace, the sofa. I willswitch the light off and turn on the spotlights in the hallway;over the front of the door. I will run from the wall and standin the spotlight. I will bathe in the light like a star and I willsay, "Thank you for coming tonight to my poetry reading."

I will be wearing the dress my mother didn't wear. It islong, black and 100 percent polyester, my favorite fabric becauseit flows. I will wear her dress and her shoes and I willbe her.

With the spotlights aimed right at me, I will clear mythroat and read a poem from her book. I will read it with herdistinctive and refined Southern inflection.

I will turn off all the lights in the house and go into mybedroom, close the door. My bedroom is deep blue. Bookshelvesare attached to the wall with brackets on either sideof my window; the shelves themselves are lined with aluminumfoil. I like things shiny.

My shiny bookshelves are lined with treasures. Empty cans,their labels removed, their ribbed steel skins polished withsilver polish. I wish they were gold. I have rings there, ringsfrom our trip to Mexico when I was five. Also on the shelves:pictures of jewelry cut from magazines, glued to cardboard andpropped upright; one of the good spoons from the sterlingsilver my grandmother sent my parents when they were married;silver my mother hates ("God-awful tacky") and a smallcollection of nickels, dimes and quarters, each of which hasbeen boiled and polished with silver polish while watchingDonnie and Marie or Tony Orlando and Dawn.

I love shiny things, I love stars. Someday, I want to be astar, like my mother, like Maude.

The sliding doors to my closet are covered with mirrorsquares I bought with my allowance. The mirrors have veinsof gold streaking through them. I stuck them to the doorsmyself.

I will aim my desk lamp into the center of the room andstand in its light, looking at myself in the mirror. "Hand methat box," I will say to my reflection. "Something isn't righthere."

Chapter Two

LITTLE BOY BLUE NAVY BLAZERMy fondness for formal wear can be traced to thewomb. While pregnant with me, my mother blasted opera onher record player while she sat at the kitchen table addressingSASEs to The New Yorker. Somehow, on the deepest, mostbase genetic level, I understood that the massively intensemusic I heard through her flesh was being sung by fat peopledressed in cummerbunds and enormous sequined gowns.

When I was ten, my favorite outfit was a navy blazer, awhite shirt and a red clip-on tie. I felt I looked important.Like a young king who had ascended the throne because hismother had been beheaded.

I flatly refused to go to school if my hair was not perfect,if the light didn't fall across it in a smooth, blond sheet. Iwanted my hair to look exactly like the mannequin boys' atAnn August, where my mother shopped. One stray flyawaywas enough to send the hairbrush into the mirror and merunning for my room in tears.

And if there was lint on my outfit that my mother couldn'tremove with masking tape, that was a better reason to stayhome than strep throat. In fact, the only day of the year Iactually liked going to school was the day the school photowas taken. I loved that the photographer gave us combs asparting gifts, like on a game show.

Throughout my childhood, while all the other kids werestarting fights, playing ball and getting dirty, I was in my bedroompolishing the gold-tone mood rings I made my motherbuy me at Kmart and listening to Barry Manilow, Tony Orlandoand Dawn and, inexplicably, Odetta. I preferred albumsto the more modern eight tracks. Albums came with sleeveswhich reminded me of clean underwear. Plus, the pictureswere bigger, making it easier to see each follicle of Tony Orlando'sshiny arm hair.

I would have been an excellent member of the BradyBunch. I would have been Shaun, the well-behaved blond boywho caused no trouble and helped Alice in the kitchen, thentrimmed the split ends off Marcia's hair. I would have notonly washed Tiger, but then conditioned his fur. And I wouldhave cautioned Jan against that tacky bracelet that caused thegirls to lose the house-of-cards-building contest.

My mother chain-smoked and wrote confessional poetryaround the clock, taking breaks during the day to call herfriends and read drafts of her latest poem. Occasionally shewould ask for my opinion.

"Augusten, I've been working on what I believe could bethe poem that finally makes it into The New Yorker. I believeit could make me a very famous woman. Would you like tohear it?"

I turned away from the mirror on my closet door and setthe hairbrush on my desk.

Continues...

Excerpted from Running with Scissorsby Augusten Burroughs Copyright ©2003 by Augusten Burroughs. Excerpted by permission.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Running with Scissors: A Memoi

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00066309783

Running with Scissors: A Memoi

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00063220387

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Dream Books Co., Denver, CO, U.S.A.

Condition: very_good. Pages are clean with no markings. May show minor signs of wear or cosmetic defects marks, cuts, bends, or scuffs on the cover, spine, pages, or dust jacket. May have remainder marks on edges. Seller Inventory # DBV.031242227X.VG

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Dream Books Co., Denver, CO, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. This copy has clearly been enjoyed‚"expect noticeable shelf wear and some minor creases to the cover. Binding is strong, and all pages are legible. May contain previous library markings or stamps. Seller Inventory # DBV.031242227X.A

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 031242227X-3-19443742

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 031242227X-4-19481976

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 031242227X-4-18830996

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Cypress, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 031242227X-3-19468723

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 031242227X-3-18684137

Running with Scissors: A Memoir

Seller: Reliant Bookstore, El Dorado, KS, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. This book is a well used but readable copy. Integrity of the book is still intact with no missing pages. May have notes or highlighting. Cover image on the book may vary from photo. Ships out quickly in a secure plastic mailer. Seller Inventory # RDV.031242227X.A