About this Item

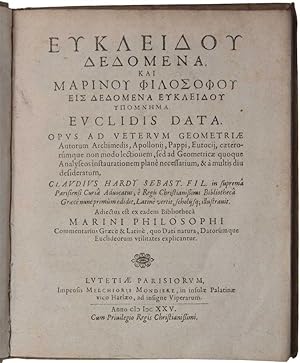

EDITIO PRINCEPS OF EUCLID'S DATA. Very rare editio princeps of this important text by Euclid, his only work in pure geometry, other than the Elements, to have survived in Greek. It is here accompanied by a commentary, or rather an introduction, by Marinus of Naples (5th century AD), the pupil and biographer of Proclus. Although the importance of the first printing of any Euclidean text goes without saying, the work is of particular interest given contemporary developments in French geometry - Descartes, Mersenne, Fermat, etc., to whose circle the translator Claude Hardy belonged. Euclid's Data opens with the passive perfect participle 'ΠεΠομενα,' which means 'given'; its Latin form 'data' remained in the title in modern times. "The Data . is closely connected with books I-VI of the Elements. It is concerned with the different senses in which things are said to be given. Thus areas, straight lines, angles, and ratios are said to be 'given in magnitude' when we can make others equal to them. Rectilinear figures are 'given in species' or 'given in form' when their angles and the ratio of their sides are given. Points, lines, and angles are 'given in position' when they always occupy the same place, and so on. After the definitions there follow ninety-four propositions, in which the object is to prove that if certain elements of a figure are given, other elements are also given in one of the defined senses" (DSB). The Data is more concerned with 'problems' than with 'theorems'. In theorems, the goal is to show the truth of a claim; in problems, it is to perform a task after being given certain objects (e.g., given a straight line segment, construct an equilateral triangle on it). The more you are 'given', the easier is the fulfillment of the task. The Data provides a mechanism for extending what one has been given by the terms of the problem. This is a tool for the solution of problems. "A clue to the purpose of the Data is given by its inclusion in what Pappus calls the Treasury of Analysis [or Collection] . The Data is a collection of hints on analysis" (DSB). The relative obscurity of the Data, compared to the Elements, might be explained by the evolution of Greek mathematics, which in its early stages focused on the solution of special problems, but later concentrated more on the systematic arrangement of theorems. This is a very rare book. OCLC lists copies at Chicago, Harvard, New York Public, Stanford, and Wisconsin in US. ABPC/RBH lists only three other copies. There are "two characteristic features of a classical analysis of a [geometrical] problem: it proceeded by means of a concept 'given,' and it was performed with respect to a figure in which the required elements were supposed to be drawn already. The latter was indicated by such phrases as 'factum jam sit,' 'Let it be done.' Which served as a standard reminder that the subsequent argument was an analysis. The at-first-sight contradictory approach, namely to assume a problem solved in order to find its solution, was seen as the essential feature of analytical reasoning. In the supposed figure some elements were given at the outset; some were directly constructible from those originally given, and some required more steps. The analysis used a kind of shorthand, codified largely in Euclid's Data, for finding the constructible ('given') elements in the figure. The geometer used that shorthand as it were to plot a path from the primary given elements to the elements he ultimately wanted to construct. "In the Data Euclid distinguished between three modes of being given: given in magnitude, given in position, and given in kind. Geometrical entities (line segments, angles, rectilinear figures) were 'given in magnitude' if, as Euclid phrased it: 'we can assign equals to them.' The third mode applied to rectilinear figures (triangles, polygons); such a figure could be 'given in kind', which meant that its angles and the ratios of its sides were given, but not its size. Seller Inventory # 3427

Contact seller

Report this item

![]()