Items related to Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Harry rescued dozens of kids - kids in crack houses, kids living in unimaginable filth and kids who had burned their houses down. Then there were the hostage situations, the lynch mobs, and the almost impossible process of interviewing paedophiles to get a confession. Without wading in sentimentality, Harry describes how his team - working alongside dedicated but chronically underfunded social workers - operated at the sharp end of child protection. This is a shocking and unforgettable story of how some of the UK's most disadvantaged children escaped their tormentors - and explains why some cases, similar to that of Baby P's, ended in tragedy.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster UK

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1847397875

- ISBN 13 9781847397874

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Shipping:

£ 4.80

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

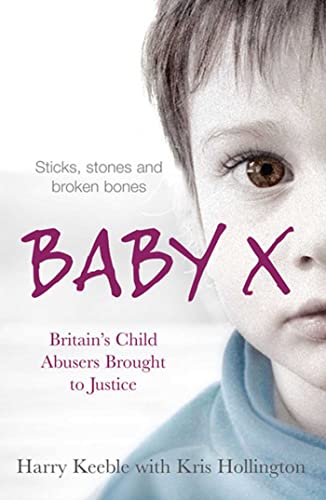

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. The book has been read but remains in clean condition. All pages are intact and the cover is intact. Some minor wear to the spine. Seller Inventory # GOR001589737

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. When super-tough cop Sergeant Harry Keeble announced he was joining Hackney's ailing Child Protection Team in 2000, his colleagues were astounded. Known as the 'Cardigan Squad', its officers were seen as glorified social workers dealing with domestics. The reality was very different. Within a few months he'd fought machete-wielding thugs, rescued kids who had pit bulls chained to their cots and confronted the horrors of African witchcraft, exposing a network of abuse in the process - all in his unrelenting war against child cruelty. Harry rescued dozens of kids - kids in crack houses, kids living in unimaginable filth and kids who had burned their houses down. Then there were the hostage situations, the lynch mobs, and the almost impossible process of interviewing paedophiles to get a confession. Without wading in sentimentality, Harry describes how his team - working alongside dedicated but chronically underfunded social workers - operated at the sharp end of child protection. This is a shocking and unforgettable story of how some of the UK's most disadvantaged children escaped their tormentors - and explains why some cases, similar to that of Baby P's, ended in tragedy. The book has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # GOR001554752

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Condition: Very Good. This book is in very good condition and will be shipped within 24 hours of ordering. The cover may have some limited signs of wear but the pages are clean, intact and the spine remains undamaged. This book has clearly been well maintained and looked after thus far. Money back guarantee if you are not satisfied. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. . Seller Inventory # 7719-9781847397874

Baby X: Britains Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Used; Acceptable. Dispatched, from the UK, within 48 hours of ordering. The book is perfectly readable and fit for use, although it shows signs of previous ownership. The spine is likely creased and the cover scuffed or slightly torn. Textbooks will typically have an amount of underlining and/or highlighting, as well as notes. If this book is over 5 years old, then please expect the pages to be yellowing or to have age spots. Aged book. Tanned pages and age spots, however, this will not interfere with reading. Damaged cover. The cover of is slightly damaged for instance a torn or bent corner. Seller Inventory # CHL9583379

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Condition: Very Good. Shipped within 24 hours from our UK warehouse. Clean, undamaged book with no damage to pages and minimal wear to the cover. Spine still tight, in very good condition. Remember if you are not happy, you are covered by our 100% money back guarantee. Seller Inventory # 6545-9781847397874

Baby X

Book Description Condition: Very Good. Book is in Used-VeryGood condition. Pages and cover are clean and intact. Used items may not include supplementary materials such as CDs or access codes. May show signs of minor shelf wear and contain very limited notes and highlighting. 0.4. Seller Inventory # 1847397875-2-3

Baby X : Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Condition: Good. Ships from the UK. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 38384955-20

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Used; Good. **SHIPPED FROM UK** We believe you will be completely satisfied with our quick and reliable service. All orders are dispatched as swiftly as possible! Buy with confidence! Greener Books. Seller Inventory # mon0001475602

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Used; Good. ***Simply Brit*** Welcome to our online used book store, where affordability meets great quality. Dive into a world of captivating reads without breaking the bank. We take pride in offering a wide selection of used books, from classics to hidden gems, ensuring there is something for every literary palate. All orders are shipped within 24 hours and our lightning fast-delivery within 48 hours coupled with our prompt customer service ensures a smooth journey from ordering to delivery. Discover the joy of reading with us, your trusted source for affordable books that do not compromise on quality. Seller Inventory # 973253

Baby X: Britain's Child Abusers Brought to Justice

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Used; Very Good. ***Simply Brit*** Welcome to our online used book store, where affordability meets great quality. Dive into a world of captivating reads without breaking the bank. We take pride in offering a wide selection of used books, from classics to hidden gems, ensuring there is something for every literary palate. All orders are shipped within 24 hours and our lightning fast-delivery within 48 hours coupled with our prompt customer service ensures a smooth journey from ordering to delivery. Discover the joy of reading with us, your trusted source for affordable books that do not compromise on quality. Seller Inventory # 3634334