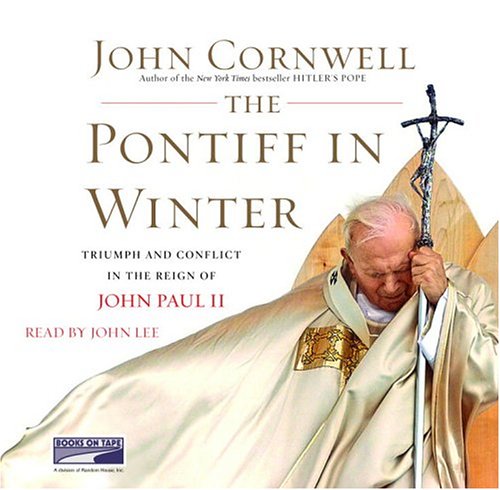

The Pontiff in Winter: triumph and conflict in the reign of John Paul II

Over more than a quarter of a century, John Paul II has firmly set his stamp on the billion-member strong Catholic Church for future generations and he has become one of the most influential political figures in the world. His key role in the downfall of communism in Europe, as well as his apologies for the Catholic Church’s treatment of Jews and to victims of the Inquisition, racism, and religious wars, won him worldwide admiration. Yet his papacy has also been marked by what many perceive as misogyny, homophobia, and ecclesiastical tyranny. Some critics suggest that his perpetuation of the Church’s traditional hierarchical paternalism contributed to pedophiliac behavior in the priesthood and encouraged superiors to sweep the crimes under the carpet. The Pontiff in Winter brings John Paul’s complex, contradictory character into sharp focus. In a bold, highly original work, John Cornwell argues that John Paul’s mystical view of history and conviction that his mission has been divinely established are central to understanding his pontificate. Focusing on the period from the eve of the millennium to the present, Cornwell shows how John Paul’s increasing sense of providential rightness profoundly influenced his reactions to turbulence in the secular world and within the Church, including the 9/11 attacks, the pedophilia scandals in the United States, the clash between Islam and Christianity, the ongoing debates over the Church’s policies regarding women, homosexuals, abortion, AIDS, and other social issues, and much more. A close, trusted observer of the Vatican, Cornwell combines eyewitness reporting with information from the best sources in and outside the pope’s inner circle. Always respectful of John Paul’s prodigious spirit and unrelenting battles for human rights and religious freedom, Cornwell raises serious questions about a system that grants lifetime power to an individual vulnerable to the vicissitudes of aging and illness. The result is a moving, elegiac portrait of John Paul in the winter of his life and a thoughtful, incisive assessment of his legacy to the Church.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

John Cornwell is the author of the international bestseller Hitler’s Pope, as well as an award-winning journalist with a lifelong interest in Vatican affairs. He has reported on the pope for Vanity Fair and The Sunday Times (London), and has written on the Catholic Church for Commonweal and the international Catholic weekly The Tablet. He attended Roman Catholic seminaries in England for seven years, followed by studies in literature and philosophy at Oxford and Cambridge universities. In 1990 he was elected a Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge, where he now directs the Science and Human Dimension Project.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

chapter one

Close Encounters

There is no substitute for the living presence, the inclination of the head, the meeting of the eyes, the idiosyncratic gesture, the tone of voice. I first met Pope John Paul II privately in his halcyon days. It was a gray morning in December 1987, and I had attended Mass in his private chapel.

Accompanied by his secretary, Stanislaw Dziwisz, a Polish priest with soft gestures and undulant step, John Paul appeared in the library of the papal apartment as if he had all the time in the world. He looked utterly centered in himself.

I noticed that his cassock was a little worn and off-white, a comfortable favorite for early mornings. He gave the impression of being equally comfortable and settled in his papacy. He was wearing a gleaming gold watch that flashed, like his pectoral cross, in the strong arc lamps. He wore a pair of stiff, shiny, fashionable tan casuals; they seemed to me, at first, incongruous, unclerical. Previous popes in this modern era had floated on felt-soled scarlet slippers.

He studied me with narrowed eyes, dragging those feet in sturdy shoes along the marble floor, somewhat pigeon-toed. "Stas" Dziwisz, the "velvet power" in the papal apartment, was whispering something in his ear. Then he was next to me, deeply stooped and hugely broad-shouldered, his legs a little apart like a hill-walker steadying himself. There was a discreet hint of peppermint and aftershave: I understood he liked Fisherman's Friend lozenges for his throat, and dabbed Penhaligon Eau de Cologne on his well-shaved jowls. His silver-white hair was inexpertly cut and slightly tousled. His familiar face, the most famous face in the world, looked drained, exhausted, as if he had not slept. Cinematically handsome from afar, he appeared, eminently, human up close. If he was a mystic, as many of his biographers claim, I sensed no numinous aura.

He inclined a large Slavonic left ear, inviting me to speak. His hand went out; as I grasped it and wondered whether I should kiss his ring, he managed to clutch my arm and push it away at the same time. His great square head went down until his chin was buried in his chest; then the eye opened, a steely knowing eye, scrutinizing me sideways. He was waiting for me to say something. I caught a sudden impression of the Niagara of sycophancy, persuasion, and petition that poured into that ear day by day. Then he turned full face on--a wide, fatherly, frank face. He began to speak, pointing his forefinger at me.

That first impression was of a man who was at once recollected and yet dauntingly observant; kindly, yet capable of stern authority. I sensed an unassailable integrity and openness, and yet there was something cunning, a peasant craftiness about the way he nailed you sideways with that eye when you least expected it. Above all, in that Vatican milieu of fleshy celibates, whose ambience was cushioned offices and plump prayer stools, he came across as a plain man who set no store by decorous niceties; an unaffected, integrated, informal, utterly human person.

His informality, setting him apart from a generation of prelates who stood on ceremonial and ecclesiastical dignity, was captured in another first encounter I had heard about.

The late Derek Worlock, Archbishop of Liverpool, was serving on a bishops' commission in Rome with Cardinal Wojtyla of Krakow, as John Paul then was in the early 1970s. One morning, according to Worlock, Wojtyla arrived late, soaked, having walked through driving rain across Rome, eschewing the use of the chauffeur-driven car to which he was entitled. Without the least embarrassment, as the assembled bishops and cardinals looked on, he first took off his shoes, then his sodden socks. Standing in bare feet, he squeezed out the water on the floor, placing the socks over a radiator to dry. Then he turned and said to the amazed prelates: "Well, gentlemen! Let's get on with it."

In his presence there is a sense of fathomless seriousness, a hint of inconsolable melancholy even. And yet you see in those intelligent, watchful eyes a ready sense of life's ridiculousness, held firmly in check. In the atmosphere of adulation that surrounds him, his minor jests are greeted with collapsing paroxysms of mirth, as when he said to Mayor Koch in New York: "You are the mayor. I must be careful to be a good citizen!" Rarely reported are his more outrageous pranks, aided by his thespian gifts. A Vatican monsignor who was in attendance on the Pope for some years told me the following revealing story:

One morning, John Paul gave an audience to a phalanx of German visitors, theologians, bishops, and VIPs. They were extremely formal and uptight, typically German. After I had shown them out of the audience room, I went back in to take my leave of the Pope. He looked me fiercely in the eye, stood ramrod straight, clicked his heels, and gave a barely perceptible but quite unmistakable little Nazi salute with a slightest gesture of the hand. It was hilarious: the Polish Supreme Pontiff sending up the Krauts! I was fit to burst out loud. Instead, insanely, I forgot myself and decided to turn the joke on him. So I gave him a look of horror, my hands on my cheeks, as if to rebuke him--as if to say: "Oh you naughty, Holy Father! What would the Germans make of your little charade?" His face darkened instantly and terrifyingly. His eyes were blazing with anger. But at that moment Ratzinger, another German, swept into the room and I had to shut the doors on them, giggling nervously to myself. Later that day, John Paul and I were alone again. He turned on me, furious, and hit me hard on the arm. It actually hurt. "I was just trying to encourage you!" he said. "Didn't you understand? I was encouraging you!" It was an odd phrase to use in English. But I understood what he meant. He meant that he was trying to amuse me or liven me up for the day. I stood there, fit to cry, because I loved him so much and I could see that I had offended him deeply. But how could I tell him that of course I had been "encouraged," that I was just engaged in a little lighthearted irony in return? I just had to let it go, leaving him to think that I was a sanctimonious, humorless idiot.

Whatever the character of the man who becomes pope, the papal role, in time, begins to take over the human being, the personality of the individual elected to the strangest, most impossible and isolating job on earth. Paul VI, Pope in the 1960s and 1970s, described the isolation thus: "I was solitary before, but now my solitariness becomes complete and awesome. Hence the dizziness, the vertigo. Like a statue on a plinth--that is how I live now."

We will never know the solitude, the psychological fragmentation, the inner sufferings that have afflicted John Paul in consequence of his papal office. But there are clues. Eamon Duffy, the Cambridge church historian, relates a story told him by a theologian friend who had been invited to dinner with John Paul II in the days when young priests were invited regularly to the papal table. This friend found himself sitting next to John Paul and decided to strike up a personal conversation rather than try to find something arresting or important to say.

He said: "Holy Father, I love poetry and I've read all your verse. Have you written much poetry since you became Pope?" To which the Pope said: "I've written no poetry since I became Pope." So the theologian said: "Well, why is that, Holy Father?" The Pope cut him dead, turning to the person on his other side.

Twenty minutes later, John Paul turned to the theologian and said curtly: "No context!" That was all.

As the dinner party broke up and the guests were departing, Duffy's friend, on taking his leave, said somewhat rashly: "Holy Father, when I pray for you now, I'll pray for a poet without context." The Pope did not respond. He just froze.

John Paul clearly felt that he had laid bare a very private part of his life. But he had imparted a tragic truth perhaps. The papal office takes over the whole person. That is what the job demands. When he said there was no "context" for poetry, he seemed to be acknowledging that in the depths of his soul, deep down where the poetry is written, there lies a terrible, vertiginous solitude.

There are many millions who have never met the Pope in the flesh but who have encountered him in their dreams. Graham Greene, toward the end of his life the most famous Catholic writer in the world, had been a friend of Pope Paul VI, who had read all Greene's books and admired them. But Greene never received a call to meet with John Paul II. When I talked with Greene not long before he died, he told me: "I dream about John Paul II. There is a recurrent dream. I am in St. Peter's Square and there are tens of thousands of people, nuns and priests and laypeople. They are all groveling on their knees, venerating him in the most repulsive fashion. And he is in their midst dispensing communion from a huge ciborium. Only, he is not dispensing the communion bread but ornate, overrich Italian chocolates." And there was another dream: "I am sitting on my balcony in Antibes having breakfast. I open up the newspaper and there's this headline: 'John Paul Canonizes Jesus Christ.' I sit there, astounded that this pope could be so arrogant as to make a saint of our Savior." Then Greene said, as if he had got to the bottom of John Paul's character: "He had a lot in common with Ronald Reagan. They were both world leaders who were in fact just actors."

Greene's antipathy toward John Paul, encapsulated in those dreams, represents a familiar reaction among many sophisticated, liberal Catholics: John Paul arrogant and autocratic, patting the heads of the faithful, John Paul obsessed with saint-making, John Paul acting a part. One wonders, though, how Greene, with his novelist's antennae, might have judged John Paul had he actu...

Close Encounters

There is no substitute for the living presence, the inclination of the head, the meeting of the eyes, the idiosyncratic gesture, the tone of voice. I first met Pope John Paul II privately in his halcyon days. It was a gray morning in December 1987, and I had attended Mass in his private chapel.

Accompanied by his secretary, Stanislaw Dziwisz, a Polish priest with soft gestures and undulant step, John Paul appeared in the library of the papal apartment as if he had all the time in the world. He looked utterly centered in himself.

I noticed that his cassock was a little worn and off-white, a comfortable favorite for early mornings. He gave the impression of being equally comfortable and settled in his papacy. He was wearing a gleaming gold watch that flashed, like his pectoral cross, in the strong arc lamps. He wore a pair of stiff, shiny, fashionable tan casuals; they seemed to me, at first, incongruous, unclerical. Previous popes in this modern era had floated on felt-soled scarlet slippers.

He studied me with narrowed eyes, dragging those feet in sturdy shoes along the marble floor, somewhat pigeon-toed. "Stas" Dziwisz, the "velvet power" in the papal apartment, was whispering something in his ear. Then he was next to me, deeply stooped and hugely broad-shouldered, his legs a little apart like a hill-walker steadying himself. There was a discreet hint of peppermint and aftershave: I understood he liked Fisherman's Friend lozenges for his throat, and dabbed Penhaligon Eau de Cologne on his well-shaved jowls. His silver-white hair was inexpertly cut and slightly tousled. His familiar face, the most famous face in the world, looked drained, exhausted, as if he had not slept. Cinematically handsome from afar, he appeared, eminently, human up close. If he was a mystic, as many of his biographers claim, I sensed no numinous aura.

He inclined a large Slavonic left ear, inviting me to speak. His hand went out; as I grasped it and wondered whether I should kiss his ring, he managed to clutch my arm and push it away at the same time. His great square head went down until his chin was buried in his chest; then the eye opened, a steely knowing eye, scrutinizing me sideways. He was waiting for me to say something. I caught a sudden impression of the Niagara of sycophancy, persuasion, and petition that poured into that ear day by day. Then he turned full face on--a wide, fatherly, frank face. He began to speak, pointing his forefinger at me.

That first impression was of a man who was at once recollected and yet dauntingly observant; kindly, yet capable of stern authority. I sensed an unassailable integrity and openness, and yet there was something cunning, a peasant craftiness about the way he nailed you sideways with that eye when you least expected it. Above all, in that Vatican milieu of fleshy celibates, whose ambience was cushioned offices and plump prayer stools, he came across as a plain man who set no store by decorous niceties; an unaffected, integrated, informal, utterly human person.

His informality, setting him apart from a generation of prelates who stood on ceremonial and ecclesiastical dignity, was captured in another first encounter I had heard about.

The late Derek Worlock, Archbishop of Liverpool, was serving on a bishops' commission in Rome with Cardinal Wojtyla of Krakow, as John Paul then was in the early 1970s. One morning, according to Worlock, Wojtyla arrived late, soaked, having walked through driving rain across Rome, eschewing the use of the chauffeur-driven car to which he was entitled. Without the least embarrassment, as the assembled bishops and cardinals looked on, he first took off his shoes, then his sodden socks. Standing in bare feet, he squeezed out the water on the floor, placing the socks over a radiator to dry. Then he turned and said to the amazed prelates: "Well, gentlemen! Let's get on with it."

In his presence there is a sense of fathomless seriousness, a hint of inconsolable melancholy even. And yet you see in those intelligent, watchful eyes a ready sense of life's ridiculousness, held firmly in check. In the atmosphere of adulation that surrounds him, his minor jests are greeted with collapsing paroxysms of mirth, as when he said to Mayor Koch in New York: "You are the mayor. I must be careful to be a good citizen!" Rarely reported are his more outrageous pranks, aided by his thespian gifts. A Vatican monsignor who was in attendance on the Pope for some years told me the following revealing story:

One morning, John Paul gave an audience to a phalanx of German visitors, theologians, bishops, and VIPs. They were extremely formal and uptight, typically German. After I had shown them out of the audience room, I went back in to take my leave of the Pope. He looked me fiercely in the eye, stood ramrod straight, clicked his heels, and gave a barely perceptible but quite unmistakable little Nazi salute with a slightest gesture of the hand. It was hilarious: the Polish Supreme Pontiff sending up the Krauts! I was fit to burst out loud. Instead, insanely, I forgot myself and decided to turn the joke on him. So I gave him a look of horror, my hands on my cheeks, as if to rebuke him--as if to say: "Oh you naughty, Holy Father! What would the Germans make of your little charade?" His face darkened instantly and terrifyingly. His eyes were blazing with anger. But at that moment Ratzinger, another German, swept into the room and I had to shut the doors on them, giggling nervously to myself. Later that day, John Paul and I were alone again. He turned on me, furious, and hit me hard on the arm. It actually hurt. "I was just trying to encourage you!" he said. "Didn't you understand? I was encouraging you!" It was an odd phrase to use in English. But I understood what he meant. He meant that he was trying to amuse me or liven me up for the day. I stood there, fit to cry, because I loved him so much and I could see that I had offended him deeply. But how could I tell him that of course I had been "encouraged," that I was just engaged in a little lighthearted irony in return? I just had to let it go, leaving him to think that I was a sanctimonious, humorless idiot.

Whatever the character of the man who becomes pope, the papal role, in time, begins to take over the human being, the personality of the individual elected to the strangest, most impossible and isolating job on earth. Paul VI, Pope in the 1960s and 1970s, described the isolation thus: "I was solitary before, but now my solitariness becomes complete and awesome. Hence the dizziness, the vertigo. Like a statue on a plinth--that is how I live now."

We will never know the solitude, the psychological fragmentation, the inner sufferings that have afflicted John Paul in consequence of his papal office. But there are clues. Eamon Duffy, the Cambridge church historian, relates a story told him by a theologian friend who had been invited to dinner with John Paul II in the days when young priests were invited regularly to the papal table. This friend found himself sitting next to John Paul and decided to strike up a personal conversation rather than try to find something arresting or important to say.

He said: "Holy Father, I love poetry and I've read all your verse. Have you written much poetry since you became Pope?" To which the Pope said: "I've written no poetry since I became Pope." So the theologian said: "Well, why is that, Holy Father?" The Pope cut him dead, turning to the person on his other side.

Twenty minutes later, John Paul turned to the theologian and said curtly: "No context!" That was all.

As the dinner party broke up and the guests were departing, Duffy's friend, on taking his leave, said somewhat rashly: "Holy Father, when I pray for you now, I'll pray for a poet without context." The Pope did not respond. He just froze.

John Paul clearly felt that he had laid bare a very private part of his life. But he had imparted a tragic truth perhaps. The papal office takes over the whole person. That is what the job demands. When he said there was no "context" for poetry, he seemed to be acknowledging that in the depths of his soul, deep down where the poetry is written, there lies a terrible, vertiginous solitude.

There are many millions who have never met the Pope in the flesh but who have encountered him in their dreams. Graham Greene, toward the end of his life the most famous Catholic writer in the world, had been a friend of Pope Paul VI, who had read all Greene's books and admired them. But Greene never received a call to meet with John Paul II. When I talked with Greene not long before he died, he told me: "I dream about John Paul II. There is a recurrent dream. I am in St. Peter's Square and there are tens of thousands of people, nuns and priests and laypeople. They are all groveling on their knees, venerating him in the most repulsive fashion. And he is in their midst dispensing communion from a huge ciborium. Only, he is not dispensing the communion bread but ornate, overrich Italian chocolates." And there was another dream: "I am sitting on my balcony in Antibes having breakfast. I open up the newspaper and there's this headline: 'John Paul Canonizes Jesus Christ.' I sit there, astounded that this pope could be so arrogant as to make a saint of our Savior." Then Greene said, as if he had got to the bottom of John Paul's character: "He had a lot in common with Ronald Reagan. They were both world leaders who were in fact just actors."

Greene's antipathy toward John Paul, encapsulated in those dreams, represents a familiar reaction among many sophisticated, liberal Catholics: John Paul arrogant and autocratic, patting the heads of the faithful, John Paul obsessed with saint-making, John Paul acting a part. One wonders, though, how Greene, with his novelist's antennae, might have judged John Paul had he actu...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBooks on Tape

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 1415916543

- ISBN 13 9781415916544

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want